Inuit Perspectives on Recent Climate Change

This article was written by Caitlyn Baikie, an Inuit geography student at Memorial University of Newfoundland and a close personal friend of mine. I am posting this on her behalf.

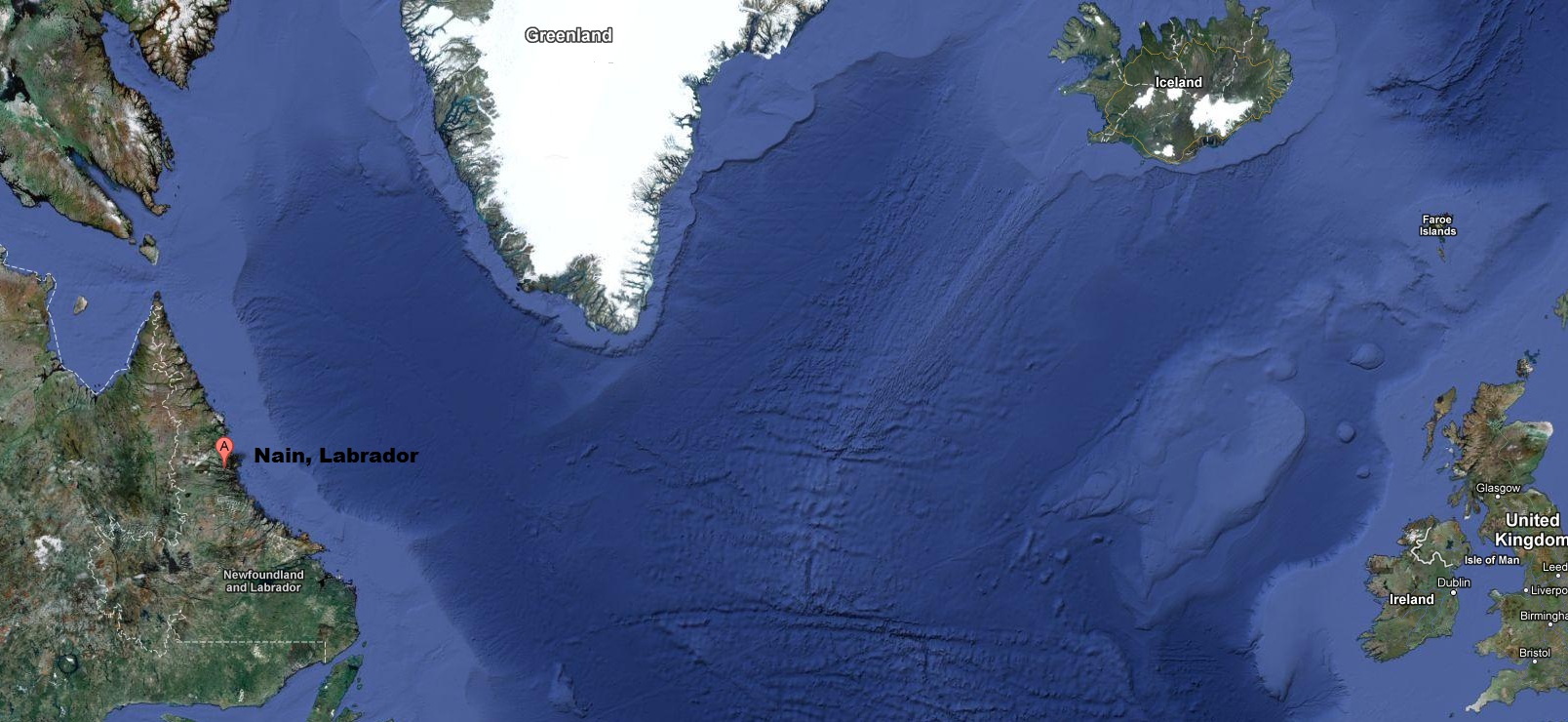

My name is Caitlyn Baikie. I am a 20-year-old Inuk from Nain, Nunatsiavut and have lived there all of my life. Nunatsiavut, in the Inuktitut language means “our beautiful land,” and what a beautiful land it is. Like Nunavut, Nunatsiavut is an Inuit self-governing territory within the province of Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada. Nain is the northernmost community on its coast, with a population of ~1200 residents, 90% of whom are of Inuit descent.

Image 1: Geographic location of Nain, Labrador (56.5°N)

My life in Nain is very different than for those who live in the city. Nain is a very isolated community, there are no roads to or from Nain, the only way to get here is by plane or boat, and in the winter by airplane or snowmobile. Though our weekdays are school and work filled as it is in the south, our recreational and sustenance activities are very different. In the winter, we go hunting for small game like partridges, which can be found locally all around the town. On weekends we often go by snowmobile on the ice to our cabins near hunting grounds where we hunt seals, caribou, ukialik (arctic hare) and migratory birds. This is when we get the bulk of our meat for the year. It is very important to get good sea ice, it provides us with the means to travel and hunt, usually for 6 months of the year. The people of Nain and the north coast are often referred to as sikimiut, people of the sea ice.

Image 2: Photograph of sea ice conditions in northern Labrador by Gary Baikie of Parks Canada.

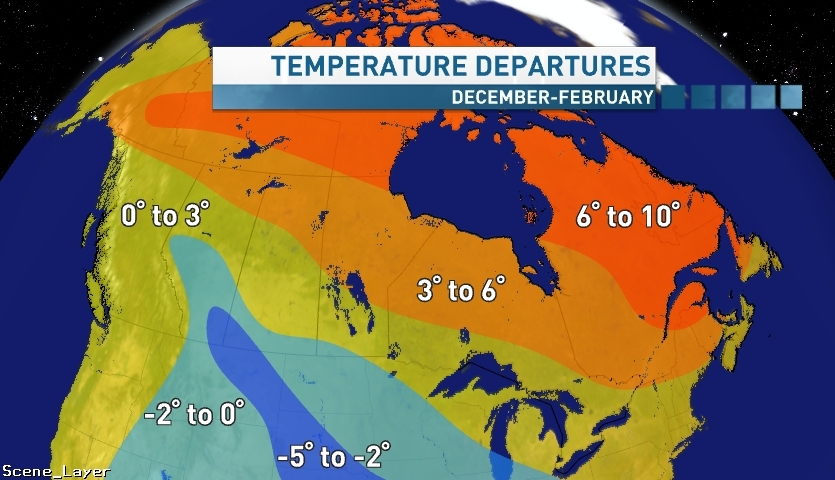

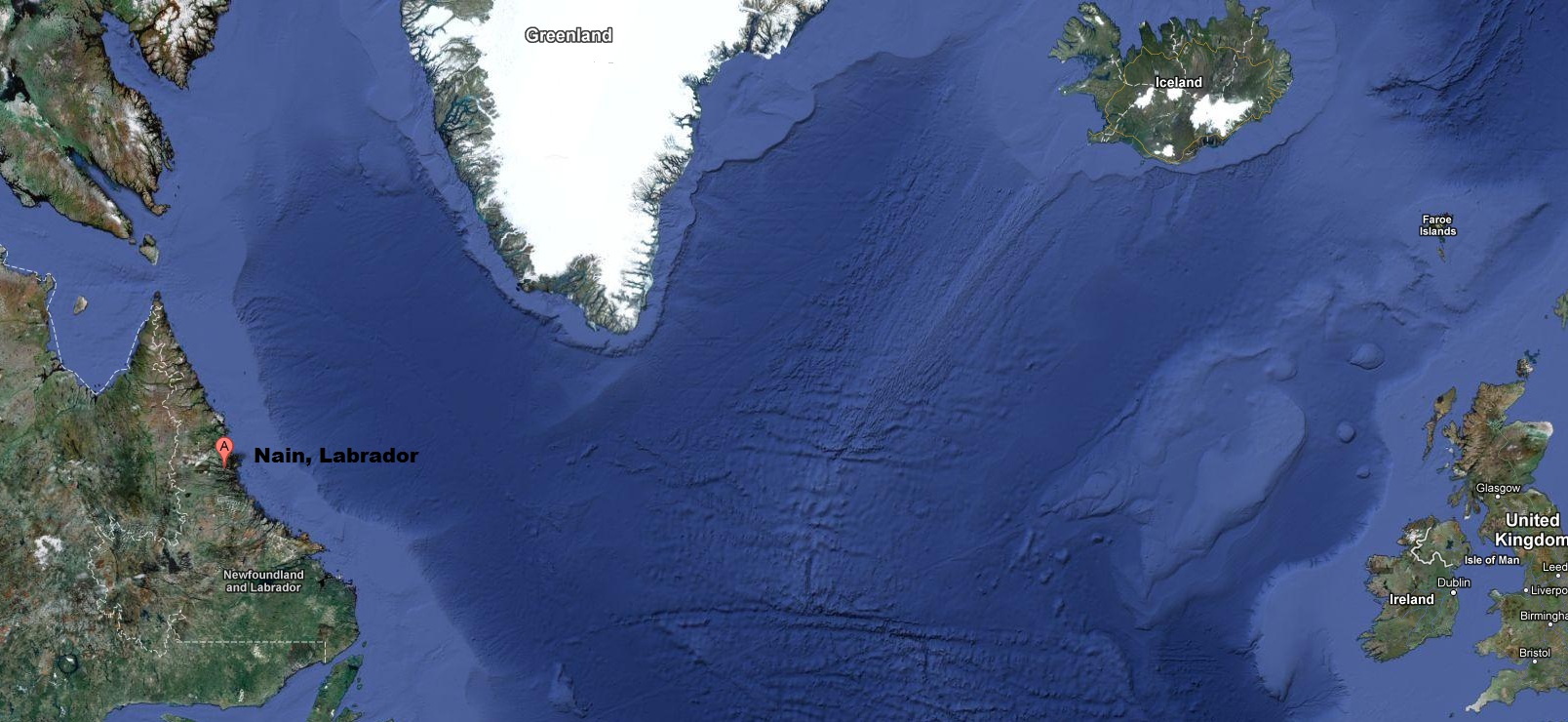

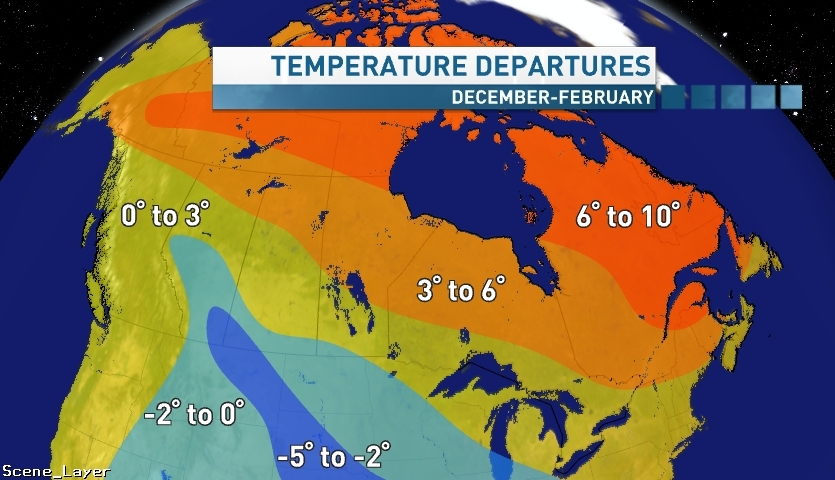

Inuit depend greatly on the sea ice also to travel to other nearby communities. However, the past few seasons have not been good for sea ice - it was not until mid-January that people first went for a snowmobile drive. This is very late considering that we are accustomed to have already travelled these routes and filled our freezers with freshly killed caribou by then. We collectively wondered if these years could just be “off”. But how far do you go in saying it’s just “off”, instead of part of something bigger? We have been faced with precipitation, and week long periods of fog and cold temperatures during our summer instead of sun and warm temperatures. Summer blends into fall, without the usual chill and freezing ground. One extreme year, 2010, our winter began promising, with some snow. But this also changed with weeks of rain. Temperatures hovered at about 0°C when the norm would have been at least -10°C. No longer are we experiencing single anomalous months but rather a change in climate which extends from season to season.

Image 3: Wintertime temperature departures for northern North America provided by Environment Canada during a newscast in 2010.

Image 3: Wintertime temperature departures for northern North America provided by Environment Canada during a newscast in 2010.

The elders have noticed this particularly. Their knowledge of our land and climate has sustained them and our people in their survival on the land for decades and it is scary to think that they have not seen a year like 2010 before. They know that our climate is changing because they have lived here for generations and these generations hold no knowledge of years like this. Our elders know from experience that our climate is changing; scientists have data that says our climate is changing (Way and Viau, In Prep).

In 2009 I had the opportunity to work alongside teams of scientists studying the climate of the Torngat Mountains National park, north of Nain. Many of the elders I know are from this land. Here, we used the knowledge of our elders and of scientists to collect data on permafrost, marine food webs, vegetation, glaciers and many other things. The results of these projects show that the park is experiencing a rapid shift in climate towards warmer conditions - glaciers are melting, vegetation growing rapidly, terrestrial biomes are greatly affected. Many universities involved in the research have begun outreach programs to help us prepare for eventual ramifications of these changes on both our physical knowledge of the land and our culture.

Image 4: Photograph of Inuit hunters in the Torngat Mountain National Park north of Nain.

Image 4: Photograph of Inuit hunters in the Torngat Mountain National Park north of Nain.

Inuit have been collecting this data for centuries, and have been passing their knowledge to younger generations. A friend of mine, an elder of Nunatsiavut, recently wrote me a letter in which he told of a hunting trip last year with my uncle and what they had observed.

“We were coming from your grandmother’s ancestral home of Nutak after a hunting and gathering trip when we went ashore to collect bake apples (cloud berries). In the area we observed that a small pond was dry even in late-September during a very wet summer.”

My uncle knew from experience and knowledge passed on to him that this boggy pond never went dry and it was in fact always a good pond to hunt geese and black ducks. The permafrost layer under the pond had melted so water could no longer be retained - this phenomenon was being observed by other Inuit hunters through northern Labrador.

There is a lot to gain from our elders’ stories, and knowledge of our land and I respect them greatly. Not only did I gain knowledge from a scientific perspective, I also spent evenings at the park with elders who shared their stories about our land. They spoke of childhood memories and what it was like to grow up on the land and how weather affected their very existence and ability to survive. The elders pointed out on maps their traditional hunting grounds, and others pointed out how some of these routes have changed over time.

As a collective, the elders have noticed that there is not as much snowfall as there used to be. They say that we don’t get near the amount of snow that they did when they were young. The elders have also noted an increased number of polar bear sightings further south. This is very unusual, and likely attributable to the lack of floe ice during the summer months, leaving polar bears no other option than to move to the land where people live. Unusual ice conditions have also brought tragedy to our communities. We have lost lives because of less predictability in ice and snow cover. A few years ago, two experienced Inuit hunters lost their lives while traveling a route that was known to them.

Image 5: Photograph of late-freeze up observed during 2011-2012's Fall/Winter.

As Inuit our lives are tied to nature and for that we have a great respect for mother nature’s strength. The land, the sea, and the climate define us as a culture, and our culture will forever be altered because of the changes we are undergoing today.

I have not come here as an expert on climate change, but as a person who sees firsthand how people are affected in every aspect of their lives by climate. I have observed that Inuit traditional knowledge supports scientific research, and it is wonderful to be a part of this collaborative effort. Inuit, collectively, do not greatly contribute to factors that lead to climate change, but we are surely amongst the greatest impacted. It is a privilege to have been invited to tell my story, and to learn from others research and experiences. Thank you. Nakummek.

Image 6: Polar bear observed on the ice near the coast of northern Labrador.

Postscript: Research examining the extraordinary nature of recent climate change in Labrador is being explored from both a physical and social perspective by researchers at the University of Ottawa and Memorial University of Newfoundland.

Posted by robert way on Thursday, 27 September, 2012

Image 3: Wintertime temperature departures for northern North America provided by Environment Canada during a newscast in 2010.

Image 3: Wintertime temperature departures for northern North America provided by Environment Canada during a newscast in 2010.