In an earlier article, I reviewed sociologist Kari Norgaard’s book Living in Denial: Climate Change, Emotions and Everyday Life in which she records the response of rural Norwegians to climate change. She analyzes the contradictory feelings Norwegians experience in reconciling their life in a wealthy country that is at once a major producer and consumer of fossil fuels and, at the same time, has a reputation of being a world leader in its concern for the environment, human development, and international peace.

Canada shares many characteristics with Norway; they are both northern lands that distinguish themselves from larger southern neighbours by their cold climates and progressive social policies. Both countries are wealthy, thanks in large part to exploitation of their abundant natural resources. In this article, I will try to look at Canada through the same lens that Norgaard used in her study of Norway. Because I am not aware of any kind of field study in Canada similar to the kind that Norgaard did in Norway, I will rely on how socially organised denial expresses itself through Canadian political discourse on climate change.

According to polling by Environics a majority of Canadians in 2012 (57%) are convinced that the science is conclusive that global warming is happening and is caused mostly by humans. Only 12% believe that the science of global warming is not yet conclusive. Majorities are also in favour of carbon taxes in most areas of the country. It is also worth noting that none of Canada's political leaders take a denialist stance on climate change. In a speech in Berlin in 2007, Prime Minister Stephen Harper affirmed his government's commitment to "...the fight against climate change, [is] perhaps the biggest threat to confront the future of humanity today." Later in the same speech he acknowledged; "But frankly, up to now, our country has been engaged in a lot of "talking the talk" but not "walking the walk" when it has come to greenhouse gases". It is that disengagement between thought and action that is at the heart of implicatory denial.

I live in the Canadian Province of British Columbia (BC), which shares many geographic features with Norway: mountains, glaciers, fjords and endless evergreen forests. Similar-sized populations enjoy very high standards of living, with economies in both places based on exploiting timber, hydroelectricity, fish, minerals, oil and natural gas. British Columbians take pride in their environmental leadership, with strong popular support for the western hemisphere’s first economy-wide carbon tax. The largest city, Vancouver is considered to be among the world’s most liveable cities and has firm intentions to become the world’s greenest city by 2020. The Provincial Government has a legislated target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, relative to 2007, by 33% in 2020 and 80% by 2050. BC voters, in 2011, were the first in North America to elect a Green Party representative, the party leader Elizabeth May, to serve in a national assembly.

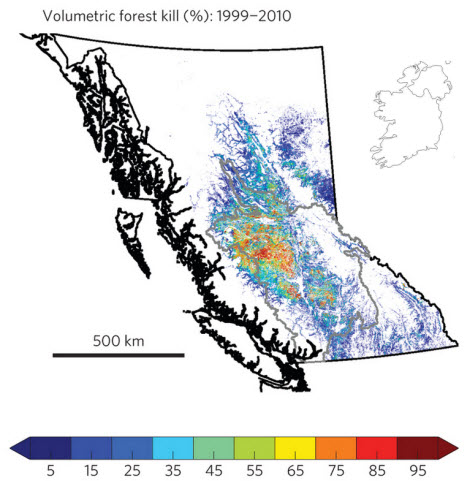

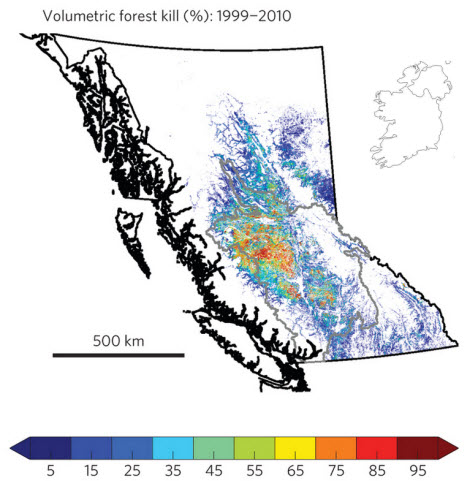

All is far from well on the ground, though. The pine forests of central BC in recent years have suffered one of the biggest impacts anywhere related to climate change. A vast area, comparable to a mid-sized European country, has suffered massive tree mortality since 2000 due to an unprecedented mountain pine beetle epidemic, linked to a series of unusually hot, dry summers and mild winters.

Forest mortality in BC between 1999 and 2010. Modified from part of Fig 1 from Maness et al (2013) (paywalled). The outline of Ireland has been added to provide scale.

Although BC’s carbon tax, now set at C$30 per tonne of CO2, is popular and effective —fossil fuel use since 2008 has dropped faster in BC than in the rest of Canada—the prospect of the province achieving its own legislated emissions targets will not be realized if plans to exploit huge fields of unconventional natural gas in the NE corner of the province come about. The proposal is to transport the gas by pipeline to Kitimat, a deep-water port at the head of a fjord on the northern coast, where it will be liquefied and exported to Asia. The project has support from both major political parties in the province, as well as from the aboriginal groups who live along the transportation corridor. BC’s carbon tax does not currently tax emissions from leaks or from deliberate venting of carbon dioxide, which comprises 12% of the gas in some deposits and is stripped from the methane at processing facilities and is simply vented without penalty into the atmosphere.

So long as you're not a lodgepole pine. Image source

British Columbia is facing some very difficult choices over the next few years as it decides between natural gas exports and meeting its self-imposed emissions targets. The politicians who believe that both can be done—along with the people who may vote for them—are living in denial.

In 2010, Calgary lawyer and conservative political activist, Ezra Levant, wrote a book titled Ethical Oil: The Case for Canada’s Oil Sands in which he made the case that Canada’s petroleum industry does not deserve the harsh criticism that it has received for the exploitation of the oil sands, because the critics give the country and the corporations insufficient credit for their good record on human rights and economic and social justice; especially when compared to other oil-producing countries such as Saudi Arabia, Iran and Venezuela. Norgaard identified similar attitudes among her Norwegian subjects, which she classified as a “claim to virtue”. Of course, such arguments are entirely beside the point; good behaviour in one domain does not excuse bad practices in another.

Alykhan Velshi, a policy analyst and former ministerial aide, set up a website called Ethical Oil to promote the oil sands, using Levant’s ideas to compare Canada’s “Ethical Oil” with the “Conflict Oil” of developing counties belonging to OPEC. Both Velshi and Levant have numerous links to senior members of the Conservative government. Velshi became Director of Planning for the Prime Minister’s Office in late 2011.

Posters from the Ethical Oil campaign in 2011. These examples and others (including spoofs) can be found on a Google image search for Ethical Oil.

The Ethical Oil website produced a series of posters promoting the oil sands, contrasting Canada’s progressive politics with repression and abuse in OPEC countries. (Leo Hickman has written an article in the Guardian, with more examples.) Few people could have fallen for the argument that because gay oil-field workers can get married in Fort McMurray—the boomtown at the hub of the oil sands—that this somehow negates the very real environmental negatives associated with producing bitumen. Mellissa Blake, the mayor of Fort McMurray objected to the use of her photo in the Ethical Oil image.

This clumsy attempt to exploit Canadians’ “claim to virtue” was counter-productive; by exaggerating the ethical claim it highlighted its absurdity and irrelevance. The adverts are no longer prominent on the Ethical Oil website. Having learned from this error, the Canadian Government is now using focus groups to hone a new $9 million ad campaign on Responsible Resource Development, designed to be uplifting and to appeal to patriotic sentiment. There’s an example video here and another here.

My country is not a country, it's winter – Gilles Vigneault

The Republican political consultant Frank Luntz met with Prime Minister Stephen Harper in 2006 and advised him: “If there is some way to link hockey to what you all do, I would try to do it” (Montreal Gazette). Harper has spent many years during his time as Prime Minister working on a book on the history of hockey, which is reportedly to be published in 2013. (Luntz, of course, is notorious for the advice he offered to George W. Bush in 2002: Should the public come to believe that the scientific issues are settled, their views about global warming will change accordingly. Therefore, you need to continue to make the lack of scientific certainty a primary issue in the debate…).

Hockey (never Ice Hockey) in Canada is more than a sport, it is a nationally unifying cultural activity like no other. It is popular throughout the country: in both English and French-speaking regions; among recent immigrants and in aboriginal communities; as a professional spectacle and as an amateur sport on small-town rinks, frozen ponds and in backyards. Climate scientist Simon Donner made a short video in 2011 about his family’s Christmas tradition of playing hockey on a frozen lake. Climate change threatens this tradition, as the lake can no longer be relied upon to freeze over in time for Christmas.

Donner’s blog post provoked angry responses from climate contrarians, which ran the full gamut from the Luntz-inspired “the science is not settled”, via Climategate and, naturally enough, the “hockey stick” historical climate graph. None of the commenters actually contested the simple observation that water bodies are tending to freeze over later in the winter.

A study by researchers in Quebec published in Environmental Research Letters in 2012, demonstrated that the outdoor skating season has decreased statistically significantly in many regions of the country, particularly in SW Canada. They conclude:

The ability to skate and play hockey outdoors is a critical component of Canadian identity and culture. Wayne Gretzky learned to skate on a backyard skating rink; our results imply that such opportunities may not [be] available to future generations of Canadian children.

There is a website called RinkWatch, which is a citizen-science project, gathering statistics on outdoor rinks. The map on the home page handily shows the outdoor rinks across Canada that are skateable or not on a given day.

The Nunatsiaqonline reports that, because of climate change, the community of Cape Dorset on Baffin Island can no longer rely on cold weather to keep its indoor rink frozen for the hockey season. It has purchased an ice-making system called eco-glace from a Quebec company. It’s an ill wind that blows nobody any good, and climate change has at least now made it possible for enterprising southerners to sell ice to the Inuit.

The back of the current Canadian five-dollar bill. The quotations in small print are in French and English, from Roch Carrier’s story The Hockey Sweater: “The winters of my childhood were long, long seasons. We lived in three places—the school, the church and the skating rink—but our real life was on the skating rink”.

All Canadian banknotes are being redesigned and the new five-dollar bill will have an image of the Canadian-built robotic arms used in space exploration. Great care goes onto the selection of the images. Using the Access to Information Act, The Canadian Press obtained heavily censored documents that record the deliberations of the team reviewing the banknote image options for the Bank of Canada. Among the comments were, incredibly:

- Pictures of wind turbines and solar panels were rejected because “clean energy is a controversial concept.”

- Images that included snow “may become more controversial should global warming progress,” and are best avoided, said some.

The review panel showed that they were sensitive to nuances of political iconography, but were not so much when it came to botanical accuracy: stylized leaves of Norwegian maples were used on the new twenty-dollar bill instead of the iconic Canadian maple leaf.

Denial of the science of climate change—the rebutting of which is the main goal of Skeptical Science—is undoubtedly an obstacle to progress. But as Kari Norgaard has shown, even people who accept the science and care deeply about the environment find ways to justify continuing to live as if their lifestyles were not part of the problem.

Developed, progressive countries with economies dependent on large fossil fuel resources, like Norway and Canada show the clearest examples of implicatory denial of climate change. But by no means do these societies have a monopoly on it. Wealthy people in all countries have been slow to change their lifestyles, including even those who are the most informed.

Climate scientist Erica Thompson, in a Viewpoint article in the journal Weather, argues that climate scientists, in particular, need to make their actions consistent with their predictions. Conferences, such as the AGU Fall Meeting, where 20,000 scientists converge every year from all corners of the planet, cannot be maintained, over coming years, if we are to meet the emissions targets advocated by many of those same scientists. As Thompson argues:

…we have a responsibility to behave in a manner consistent with that belief [the belief that the balance of evidence suggests climate change represents a real threat]. That means making real and meaningful efforts to reduce our own carbon footprints, both at an individual and institutional level.

And in any case, we have no choice. The UK’s ‘legally-binding’ target of an 80% reduction means that, by 2050, one long-haul flight per year will use up more than an individual’s fair share of emissions. If we are going to continue to do good science in a low-carbon future, then we need to find more efficient ways of working.

Many of us who are alarmed about climate change nevertheless continue to act, as if we were repeating some version of St Augustine's famous prayer: Grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.

Posted by Andy Skuce on Friday, 1 March, 2013

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |