The 46th annual American Geophysical Union (AGU) fall meeting was held last week in San Francisco. Over 22,000 Earth and space scientists converged on the Moscone Center to discuss the latest cutting edge science, much of it related to climate change. The only downside to the conference was the sheer volume of interesting talks, forcing attendees to choose the most relevant to their fields of research. However, many of last week's talks are available for online viewing, currently free using the promo code AGU13.

My colleague John Cook (@skepticscience) of the University of Queensland Global Change Institute gave three talks related to climate literacy and communications. In the first he discussed the success of our approach in combining traditional science communications channels (peer-reviewed journals and press releases) with modern channels like social media to communicate our result finding a 97 percent expert consensus on human-caused global warming in the peer-reviewed literature, with great success.

Similarly, I (@dana1981) presented a poster (which can be viewed in the ePosters) outlining effective methods to communicate science via social media, based on our consensus paper communications success. Cook also discussed communicating the rapid continuation of global warming in terms people can visualize, like 4 Hiroshima atomic bomb detonations per second. For those who prefer a cuddlier comparison, Cook converted this to units of kitten sneezes – 7.4 quadrillion per second.

When accounting for all heat accumulating in the climate system, global warming is proceeding at 7.4 quadrillion kitten sneezes per second. Image created by John Cook at Skeptical Science, photo courtesy of fanpop.com.

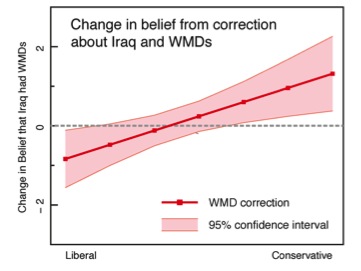

Cook also showed that when presented with facts, a worldview backfire effect can actually reinforce belief of misinformation. For example, in one experiment, American conservatives were more likely to believe there were WMDs in Iraq when presented with evidence to the contrary.

Change in belief across the political spectrum when presented with evidence there were no WMDs in Iraq. Conservative belief of the myth actually increased.

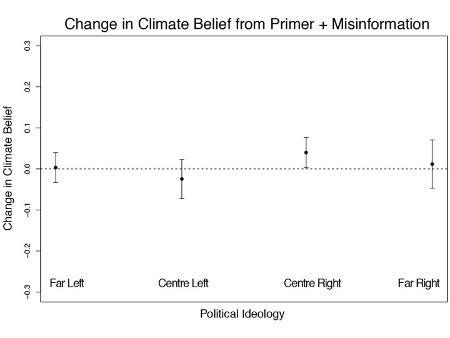

However, Cook found that priming people by first explaining the origin of the myth, also known as agnotology-based learning, is an effective myth-debunking approach. In fact, presenting only a primer (discussing tobacco industry use of fake experts) prior to the myth (that the Oregon Petition proves there is no consensus on global warming) negated the effect of the myth across the political spectrum, without even presenting the facts (97 percent expert consensus).

Change in myth belief across the political spectrum when primed and then presented with a myth. Courtesy of John Cook.

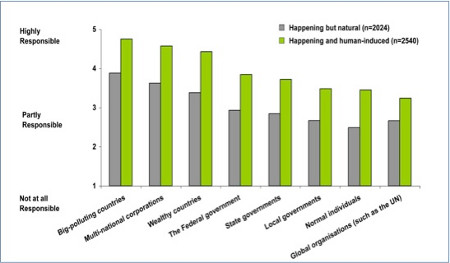

Stephan Lewandowsky (@STWorg) of the University of Bristol argued that climate contrarians should be exposed for spreading misinformation, not engaged. With that approach, open-minded people can see the source of misinformation, as in Cook's agnotology-based learning approach. This would avoid wasted effort in trying to avoid polarizing the small minority who are in denial. Lewandowsky presented some interesting results showing that those who claim to believe global warming is natural nevertheless blame it on the same human sources as those who respond that it's human-caused (though to a lesser degree). This suggests that people who say global warming is natural subconsciously know it's not.

Responses to the question 'who is responsible for global warming'. The distribution is the same for those who respond it's natural vs. responses that it's human-caused. Courtesy of Stephan Lewandowsky.

Susan Hassol shared some excellent new videos from climatecommunication.org (@climatecomms), explaining important climate science concepts in simple language. She was also among several presenters to discuss the effectiveness of The Escalator in debunking a popular myth with a simple and effective animated graphic.

Average of NASA GISS, NOAA NCDC, and HadCRUT4 monthly global surface temperature anomalies from January 1970 through November 2012 (green) with linear trends applied to the timeframes Jan '70 - Oct '77, Apr '77 - Dec '86, Sep '87 - Nov '96, Jun '97 - Dec '02, and Nov '02 - Nov '12. Courtesy of Skeptical Science.

Naomi Oreskes from Harvard discussed that people may not understand the urgency of climate change because while climate scientists' research shows that the potential consequences of global warming are alarming, their tone does not reflect that alarm. As Oreskes put it, climate scientists are afraid of sounding like they're crying wolf, but as a result we're fiddling while Rome burns. She also discussed climate scientists' tendencies toward overly conservative predictions, "erring on the side of least drama."

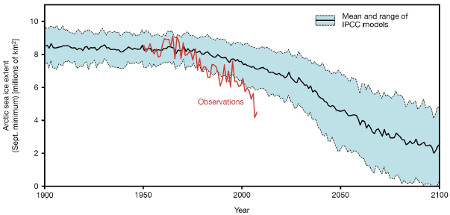

Oreskes contrasted this approach with doctors, who will err on the side of being overly cautious because, for example, failing to diagnose cancer is much worse than an incorrect cancer diagnosis. When it comes to climate change, contrarians pounce on every prediction that turns out to be an over-estimate, but we hear very little about the dramatically under-estimated Arctic sea ice decline, for example. Oreskes postulates that this one-sided attack is resulting in "seepage," making climate scientists overly cautious.

Observed vs. IPCC modeled annual minimum Arctic sea ice extent, from the 2009 Copenhagen Diagnosis.

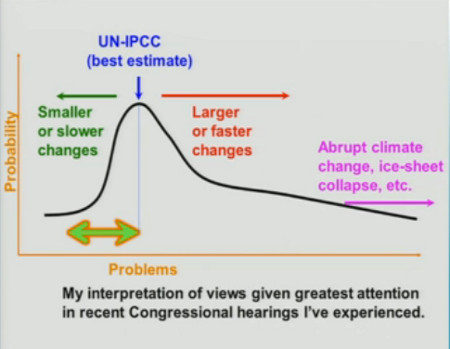

Richard Alley from Penn State discussed the potential for rapid climate change due to ice melt and associated sea level rise, and possible large releases of methane into the atmosphere. He concluded that most of the abrupt and potentially catastrophic climate change scenarios are unlikely to happen this century, but we can't completely rule them out either. The most likely such scenario would be associated with large volumes of ice in Antarctica collapsing into the ocean if relatively small buttresses of ice holding them in place melt. This could result in a rapid and large rise in sea levels. Unfortunately the 'debate' is between the most likely and best case scenarios, and the worst case scenarios are largely ignored.

The range of possible climate outcomes, with policymakers focusing on the best case and ignoring the worst case. Courtesy of Richard Alley.

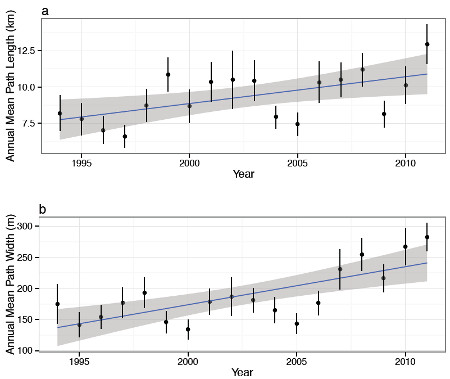

Recently there's been some controversy surrounding climate change and tornadoes, with experts criticizing non-experts for making factually incorrect statements in the media, and similar comments being made in a recent Congressional hearing on weather and climate. James Elsner (@hurricanejim) from Florida State presented his most recent, preliminary data showing that tornado path lengths and widths have increased in the US, suggesting that overall tornado energy and intensity may have increased as well.

US tornado path length and width changes from 1994 through 2011. Courtesy of James Elsner.

Gavin Schmidt (@ClimateOfGavin) gave an insightful talk addressing the debate as to whether climate scientists should engage in "advocacy," and what constitutes advocacy. For example, most scientists would be willing to say that more resources should be devoted to science education and research, and that would constitute advocacy. Schmidt presented the following Venn diagram illustrating how science, values, and advocacy can overlap.

Posted by dana1981 on Tuesday, 17 December, 2013

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |