(with apologies to Arnold Munk)

A couple of years ago, on a panel TV show about climate change on the BBC, an audience member commented that they thought the idea that humanity could influence something like the earth's climate was arrogant. There is an important insight here if we unpack this thought a little.

Is it arrogant to think we should seek to influence the climate? Yes, possibly, depending on your point of view. But that wasn't their point I think. Their point was that thinking we could influence the climate is arrogant. But it isn't arrogant; neither is it humble.

It is a measurement.

How powerful does 'something' have to be to influence the climate? And how powerful are we now? Both of these are questions that we can estimate quantitative answers to.

The simple fact is, that over my lifetime - I was born in 1957 - or somewhat longer, humanity's power has grown enormously, and we haven't really noticed. This has been called the Great Acceleration and it has happened in one lifetime.

So lets look at some measurements, some data on just how powerful we have become.

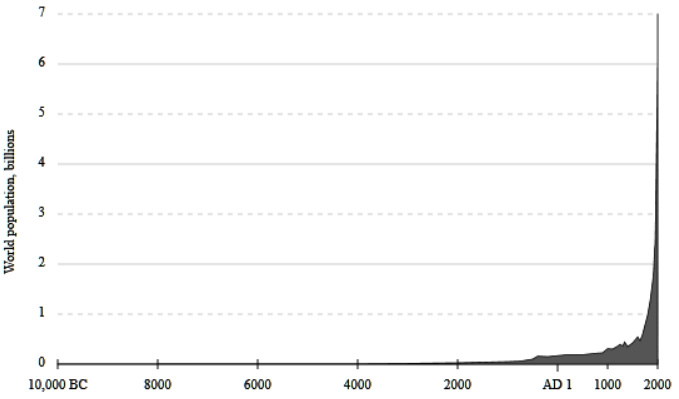

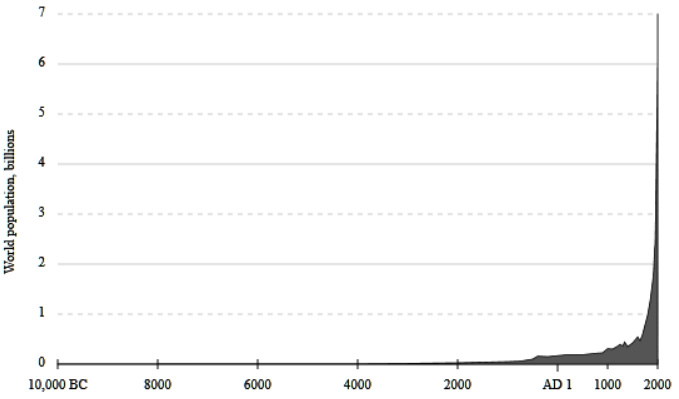

For most of human history the world's population was less than one billion people. In the time of Christ it was perhaps 200-300 million. We only reached one billion around 1800, two billion around 1925, three billion around 1960. We have added a billion people every 14 years or so since then.

"Population curve" by El T - originally uploaded to en.wikipedia as Population curve.svg. The data is from the "lower" estimates at census.gov

For a child born after the end of WWII, the world's population tripled in their lifetime. This has never ever happened to any other generation before them in all of history, and is unlikely to ever happen again. They, we, are a unique generation in history.

My parents, their children and grandchildren have lived through the most momentous change in all of human history. Not simply the rise of technology, the electronic revolution, space travel. But more importantly sanitation, medicines and contraception - my grandfather was one of 8 children, only 4 survived to adulthood. Today we would be appalled by this. For all of our ancestors this was normal.

Our ancestors would be utterly astounded; ours would seem an alien world where such change is possible.

Because for them things changed little in a lifetime. A citizen of the 6th century would see little different if they traveled 100 years into the future; kings and princes come and go, perhaps lines on maps change, but ordinary daily life hardly changed in a lifetime.

But for us it feels normal that such vast change occurred because that is just what happened. We don't have a frame of reference, deep inside, to know that today is utterly astonishing; we have stepped outside of everything our ancestors called normal.

Yet unconsciously we possibly still project our ancestors view of themselves onto our lives today as well; that is the view we inherited from them. We don't realize that we are alienated from them, to them we are 'strangers in a strange land'.

If the power of humanity depends on how many of us there are, our power has tripled in a single lifetime. If ever there were to be a day when we had the power to significantly impact the planet, surely it is today; our power has grown 25-30 fold since the time of Christ, just on numbers alone.

But we haven't just multiplied in numbers. So many of us, as individuals, are far, far more powerful than our ancestors could ever have dreamed of being.

Recently I added a veranda to my house. I needed a machine to drill the post holes for the veranda posts. I drove a small SUV with a trailer to a nearby town to hire a machine to excavate the post holes and return it the same day. The machine had a 25 horsepower (HP) motor. My car had a 130 kW engine - roughly 175 HP.

Just to drill some holes in the ground, I had access to the average power of 200 horses! In centuries past what would you have called someone who could muster 200 horses to a task when they needed to? A very wealthy and powerful man; it probably would have been a man back then. But I, as an ordinary citizen, could now muster that just because I needed it.

When you are ironing a shirt, look at the rating plate on the iron. Usually the iron is 1400-1600 watts - two HP. Two horses available to you just so you can iron a shirt!

When Australia was being settled by Europeans (native Australians rightly prefer the word invaded) the journey from the city of Melbourne to my town took around 10 days on foot. Now I can commute that distance for work in 1 1/2 hours.

There are so many more of us, and we are so much more powerful than all of our ancestors. But we don't notice because that is all just normal now. The utterly extraordinary is just mundane to us.

Do you eat meat? A hamburger, chicken risotto, roast lamb, bacon? Drink milk, eat eggs, cheese, yoghurt? All obtained from our domesticated animals. Just how much of the world is made up of us and our domestic animals? How much is still 'wild' animals?

Here are some examples of the numbers of different species:

| Species | Number per species (approx) | Domesticated | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Apes & Primates | Homo Sapiens | 7,300,000,000 | Yes? |

| Borneo Gibbon | 250-375,000 | No | |

| Chimpanzee | 170-300,000 | No | |

| Western Gorilla | 95,000 | No | |

| Orangutan | 45-70,000 | No | |

| Most small primates | 1000's to 10's of 1000's | No | |

| Carnivores | Dogs | 400,000,000 | Yes |

| Cats | 600,000,000 | Yes | |

| American Black Bear | 900,000 | No | |

| Brown Bear | 200,000 | No | |

| Bush Dog | 110,000 | No | |

| Sea Otter | 100,000 | No | |

| Leopard | 75,000 | No | |

| Lion | 30-40,000 | No | |

| Polar Bear | 20-25,000 | No | |

| Tiger | 4,000 | No | |

| Sea Lions and Seals | 10's of 1,000,000's | No | |

| Ungulates - Hoofed Animals |

Cattle & buffalo | 1,400,000,000 | Yes |

| Sheep & Goats | 1,900,000,000 | Yes | |

| Pigs | 980,000,000 | Yes | |

| Mules | 10,000,000 | Yes | |

| Donkeys | 40,000,000 | Yes | |

| Horses | 58,000,000 | Yes | |

| Impala | 2,000,000 | No | |

| Springbok | 2,000,000 | No | |

| Zebra | 660,000 | No | |

| Elk | 1,500,000 | No | |

| Blue Duiker | 7,000,000 | No | |

| Wildebeest | 1,500,000 | No | |

| Hippopotamus | 125-148,000 | No | |

| Giraffe | 80,000 | No | |

| Elephant | ~ 500,000 | No | |

| Most other ungulates | 100's of 1000's. | No |

And there are nearly 20 billion chickens!

All told, it is estimated that, of the mass of all land vertebrates, humanity and our domesticated animals make up over 95%. By weight, of all higher land animals - mammals, birds, reptiles and amphibians - less than 5% are 'wild'. We have nearly domesticated the wild.

Humanity has a population of around 7.3 billion people. The land surface of the earth is around 15 billion hectares. So that is roughly 2 hectares per person (5 acres). Not all that land is usable; some is ice caps, mountain ranges, deserts. So perhaps 1.75 hectares per person.

The land area isn't growing, but our population has. When I was born that figure was more like 5 hectares per person. If as projected world population climbs to 10-11 billion people by later this century, that figure will fall to not much more than 1 hectare per person (2.5 acres).

Imagine you had to survive on 1 hectare of 'average land'.

Some typical farmland near Canberra, Australia

Grow all your food, produce your clothing, have a home, possessions, tools and utensils, water supply for yourself and to grow your food just from the rain that falls on your land, provide power, heating and cooling for yourself, dispose of all your wastes and rubbish - when you use the lavatory, throw out the trash, it doesn't leave your land. You need to filter the water you use, even replace the oxygen you breath with the plants on your land.

And you need to do this in perpetuity; when you die (and are buried or cremated on your 1 hectare) it needs to be passed on so the next person can live off it, and the next. You need to maintain the nutrient levels in the soil so you and they can keep on growing food. You need to limit soil erosion and drying so that soil isn't lost faster than new soil can be created.

Could you do it? Could you survive completely, permanently, on just one hectare of 'average' land? Or do you survive by using up your hectare and leaving nothing left for later? Suddenly the difference between 5 hectares per person when I was born and only 1 hectare per person later this century sounds very 'challenging'. At the time of Christ the figure was more like 50 hectares per person.

Still confident we don't have much impact?

Humanity's total rate of energy consumption, how fast we use it, is estimated at about 18 trillion watts. And if every person on the planet had the lives and energy consumption of we in the developed nations that figure would be more like 60-80 trillion watts.

That's a big number; how big? For comparison, the total flow of heat from within the earth, all of geothermal heat, is estimated to be 44-47 trillion watts. And that is the heat flow that drives geology - mountain building, continental drift, eruptions, earthquakes.

Our use of energy is now at a geological scale. Potentially rising to nearly double all of geothermal heat. Because there are so many of us, and we have access to so many 'horses'.

If we just ignored 'incidental' issues like climate change, that humanity would still be able to burn all the coal we have there might be enough for maybe several centuries before we used it all up. This coal has been laid down over 100's of millions of years. The peak of coal formation was during the Carboniferous period but some coal has been laid down over much of the last 400 million years. And we could use it all up in a few centuries!

So a quantity of coal that took centuries to be laid down - we burn that in one DAY!

We can examine the data from ice-cores to look at how fast carbon dioxide (CO2) concentrations in the atmosphere changed over past glacial cycles over 100's of 1000's of years as the vast ice sheets expanded and contracted.

Vostok Antarctic ice core records for carbon dioxide concentration (Petit 2000) and temperature change (Barnola 2003). For comparison, today's levels of 400 ppm are more than twice the height of this graph.

The fastest rate of change in concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere was around 1 part per million (ppm) per century.

Today CO2 concentrations are changing at around 1 ppm every 23 weeks!

When we look back through the deep geological record, going back 500 million years or so, only one period appears to have perhaps seen changes in CO2 concentrations as fast or faster than we are changing them today. That was around 250 million years ago at the end of the Permian Period. This was the time of the greatest mass extinction event in history. 75% of all species on land went extinct; 96% of species in the ocean. Ocean temperatures near the equator peaked at nearly 40 C, the land was hotter. Possibly no new coal was laid down for 10 million years after this event - the so called 'Coal Gap' - because the forests of the world were decimated. Vast amounts of soil flooded into the seas as erosion scoured the continents.

No other event from the past matches what we are doing to CO2 levels today.

Because with so many people, and so many 'horses', and so much technology, we can excavate and burn things far, far faster than Mother Nature ever created them.

Here is a back-of-the-envelope calculation; just how much 'stuff' do we dig up each year?

We mine around 9 billion tonnes of coal each year, 3.5 billion tonnes of iron ore. Maybe 1 billion tonnes of copper ore, 300 million tonnes of aluminium ore. Then there are the dozens and dozens of other minerals and ores we mine in quantities of 100's and 10's of millions of tonnes. To make my wedding ring somewhere in the world there are many, many kilograms of slag left over from mining the gold ore.

So maybe 20-30 billion tonnes of all ores in total.

But as any mining engineer or geologist will tell you, you don't just dig up ore. First you have to get to it. You have to remove ordinary rock to get to the ore-body. This is called, perhaps disparagingly, 'overburden'. Typically one needs to remove 2-3 times as much overburden as there is ore to be mined. For example, in the recently cancelled expansion of the Olympic Dam uranium and copper mine in South Australia, the plan required the removal of 40 billion tonnes of overburden to get to the ore.

So 20-30 billion tonnes of ore a year and 2-3 times that in overburden; that is perhaps 60-120 billion tonnes a year.

Now what about cement? World production of cement is around 4 billion tonnes a year. And as any DIY Dad will tell you, the recipe for concrete is 1 part cement, 2 parts sand, 4 parts gravel. So 24 billion tonnes of sand and gravel is needed to turn that cement into concrete. But it doesn't stop there; we use 'aggregate' - sand, gravel, rock - to be the base of roads, back-fill for dam walls, retaining walls, gravel driveways, sea dikes, you name it. World quarrying production of aggregate is around 40-50 billion tonnes a year.

So each year we dig up 100-170 billion tonnes of 'stuff'; that's not counting 'minor' things like plowing fields etc.

So what is this 100+ billion tonnes of rock that we dig up each year, what is that equivalent to?

Lets consider the Himalayas.

They, with the Hindu Kush, cover an area of around 1 million square kilometers. And they are rising at around 5 millimeters a year. That is 5 billion cubic meters of extra rock being raised every year; the power of geology at work.

Rocks vary in their density but a typical value is around 2.7 times the density of water. So the Himalayas are pushing up around 13.5 billion tonnes of extra rock every year.

But human mining and quarrying is digging up 100-170 billion tonnes a year; 7-11 times as much. So if we sent all the worlds miners and quarriers to the Himalayas and said 'go for it', what would they be able to achieve? Instead of the Himalayas rising at 5 mm a year, they would start to fall at 30-50 mm a year! Doesn't sound like much does it? That's only 30-50 meters every 1000 years; 3,000 to 5,000 meters in 100,000 years. Hmmm, maybe not so trivial.

Our mining and quarrying activities around the world, today, are the equivalent of leveling the Himalayas in 100-200,000 years. And they have been rising for 10-20 million years! We are moving rock 100 times faster than the forces that are raising the Himalayas. If we set our miners and quarriers loose on all the worlds mountain ranges - not just the Himalayas but the Andes, the Rockies and Sierras, the Alps and Pyrenees, the Atlas, Ural and Karakoram mountains - they would level them all in 1 to 2 million years.

Gratuitous photos of wonderful scenery

All the world's great mountain ranges, that have taken 10's of millions of years to form, we could level them in much less than 1/10th of that time.

That is the scale of what we are doing right now, today!

We are now the most powerful geological force on the planet. Because there are now so many of us, and we harness all those 'horses', and all our technological knowledge, and all the energy from all those ancient fossil fuels, to move mountains. All of them if we want.

A little known commission, the International Commission on Stratigraphy (ICS), is currently deliberating on a name. The ICS sets the exact description for the names and time definitions of every geological age and time period; 'this time period is defined by these strata at these locations between this time and that time'.

And currently they are considering the most recent geological time period to be defined. It has been in colloquial use since around 1980. But they want to formalise it.

The time period is called the Anthropocene. The geological Age of Man. When humanity became so powerful that we left our mark on the rocks themselves.

For future geologists will see the changes we wrought. The ore-bodies strangely truncated and missing, the vast holes in the earth filled with newer sediments, the signatures of chemical changes from the oceans and the atmosphere, our fossilised technological rubbish. That some great upheaval, as great as many geological events of the past, and happening in the blink of an eye geologically speaking, transformed the earth.

We are now truly powerful. Yet deep inside, we haven't noticed, we haven't 'groked' it. Mainly we still live out our days, projecting our personal lives and day-to-day experiences onto the wider world around us, finding it hard to grasp how changing the scale of our actions changes everything else.

A chihuahua in a china shop can't do much damage. A bull can. So the bull has to be so much more careful. And we are like that bull now. We need to be so careful because we have grown so powerful.

When you look around the world, at how we live our daily lives, how everything is organised and managed, do you see that need for care reflected in all our choices and actions? For strength, power, can do wonderful things, it can also do terrible things; power is neutral. It is the care we take in our choices that determines what happens.

Or are we like that chihuahua; happy, and exuberant and careless, because it doesn't realise how strong it has grown? Smashing up the china shop.

We now truly are the 'Little Ape That Could'. But most of us haven't noticed.

------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Greg Craven has some thoughts about this subject here.

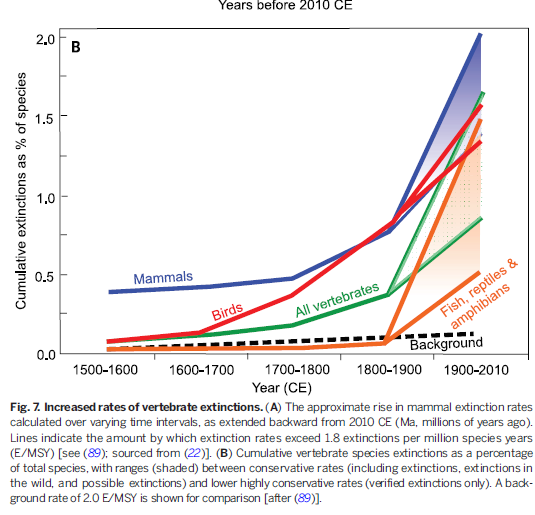

Some compelling data on how our ability to 'change stuff' is impacting many species can be found here.

Hans Rosling has some good insights into the role of population size and what we can, and can't do about it here.

To get a sense of timescales, magnitudes, and how we fit in, try this.

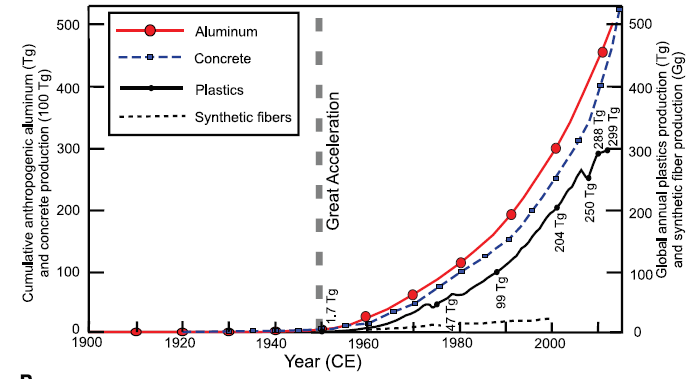

And just as I finished drafting this article, the following was published in the scientific literature

Abstract:

Human activity is leaving a pervasive and persistent signature on Earth. Vigorous debate continues about whether this warrants recognition as a new geologic time unit known as the Anthropocene. We review anthropogenic markers of functional changes in the Earth system through the stratigraphic record. The appearance of manufactured materials in sediments, including aluminum, plastics, and concrete, coincides with global spikes in fallout radionuclides and particulates from fossil fuel combustion. Carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus cycles have been substantially modified over the past century. Rates of sea-level rise and the extent of human perturbation of the climate system exceed Late Holocene changes. Biotic changes include species invasions worldwide and accelerating rates of extinction. These combined signals render the Anthropocene stratigraphically distinct from the Holocene and earlier epochs.

Some graphs from the paper, indications of the scale of some things we are doing:

Posted by Glenn Tamblyn on Thursday, 21 January, 2016

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |