A batch of stolen emails was released to the public, with evidence pointing towards Russian hackers. The media ran through the formerly private correspondence with a fine-toothed comb, looking for dirt. Although little if any damning information was found, public trust in the hacking victims was severely eroded. The volume of media coverage created the perception that where there’s smoke, there must be fire, and a general presumption of guilt resulted.

The year was 2009, and the victims were climate scientists working for and communicating with the University of East Anglia. The story was repeated in 2016 with the Russian hacking of the Democratic National Committee.

After 1,000 of climate scientists’ private emails were stolen and published online, snippets of text were taken out of context and misrepresented to falsely accuse the scientists of scandal, conspiracy, collusion, falsification, and illegal activities. Climate deniers and biased media outlets whipped up such froth over these misrepresentations that various organizations launched nine separate investigations to identify any possible scientific wrongdoing uncovered by the emails. They found none.

Nevertheless, “Climategate” caused temporary erosion in public trust of climate scientists. Like most such news events, people quickly forgot and the effect soon faded; however, the stolen emails were made public just a month before the Copenhagen international climate summit. The well-timed release of the hacked emails provided a distraction that helped sink the negotiations, which were generally viewed as a failure. A serious international climate agreement was delayed for another six years.

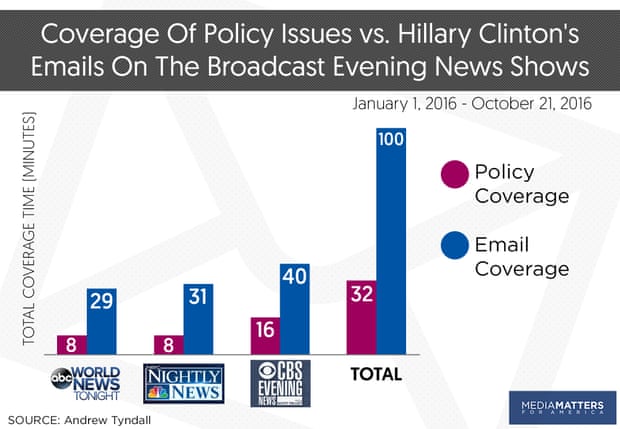

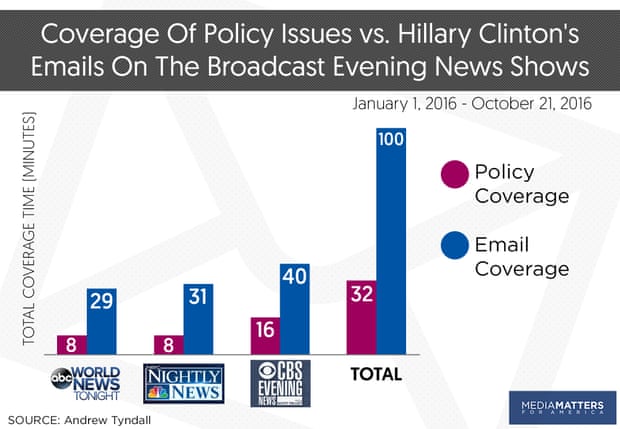

Similarly, the stolen emails released by Wikileaks did not identify any damning revelations about Hillary Clinton. The leaks had the desired effect – Clinton’s emails received three times more nightly news network coverage than all policy issues combined.

Gallup consistently found that Clinton’s emails were dominating the newsAmericans were receiving about her. The constant flood of overwhelming media coverage of the emails created the perception that Hillary Clinton was somehow ‘just as bad’ as Donald Trump.

Although Clinton won the popular vote by a margin of over 2% and close to 3 million votes, the email effect helped Trump win the election.

As President Obama said at his year-end press conference last Friday:

This was not some elaborate complicated espionage scheme. They hacked into some Democratic party emails that contained pretty routine stuff, some of it embarrassing or uncomfortable, because I suspect that if any of us got our emails hacked into, there might be some things that we wouldn’t want suddenly appearing on the front page of a newspaper or telecast even if there wasn’t anything particularly illegal or controversial about it. And then it just took off. And that concerns me. And it should concern all of us.

The exact same could be said of the hacked Climategate emails. The contents of the emails were so benign that those trying to attack climate scientists were forced to take statements out of context. For example, a sentence using the word “trick” as in “technique” was distorted and claimed to mean the scientists were nefariously trying to trick people. And the distortions worked. The media treated the hacked emails like a scandal, and the scientists who were its victims were treated like criminals. Even Jon Stewart jumped on the faux scandal bandwagon.

At the American Geophysical Union conference last week, attorney Michael Mandig, who represents Dr. Malcolm Hughes and other climate scientists on behalf of the Climate Science Legal Defense Fund, put his finger on the problem:

Having general, open access to a researcher’s email is the functional equivalent of eavesdropping.

Those trying to block climate policy by any means necessary have resorted to trying to make scientists’ private emails public, via either hacking or frivolous Freedom of Information Act requests. But there’s no reason to electronically eavesdrop on private discussions between scientists. As Dr. Hughes noted:

Email has enabled collaboration without geographical limits in science to an extraordinary degree. Treating scientists’ emails as public records, subject to twisting by anti-science ideologues, chills the vital expression of competing, and changing, views on which science depends.

Science is a competition of ideas, and scientists are critical of each others’ work. Informal discussions between scientists, whether over the telephone or in hallways or via email, depend on privacy to allow the free and frank exchange of ideas.

As President Obama noted, everyone says things in private emails that we wouldn’t want aired in public. Climategate and the 2016 presidential election provided perfect examples – despite no incriminating content, the media treated both events like scandals, and public perception of climate scientists and Hillary Clinton were damaged as a result.

For the climate scientists who lived through Climategate, the Wikileaks email scandal crated a sense of déjà vu. In both cases, the Russian petrostate may have been the perpetrator of the illegal email hacks, and emerged as the winner of the faux scandals, while the rest of us lost.

By helping elect Donald Trump, Russia now has a friendly American leadership replacing an outgoing administration that sought to punish their invasion of Ukraine and bombing in Syria. Russian operatives covertly interfered with the American election to aid Trump’s campaign, and Americans responded by electing Vladimir Putin’s preferred candidate. Russian agents may also have been behind the Climategate email hack (although the perpetrators were never identified), and again they achieved their intended goal of shaking public trust in their victims, and disrupting the Copenhagen conference.

Posted by dana1981 on Thursday, 22 December, 2016

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |