One of the largest sources of CO2 pollution from the average American consumer is the family car. The EPA states that 26% of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions come from all forms of transportation (2014 figures). The largest source of GHG emissions, at 30%, is the electric power sector. However, just recently the Energy Information Administration (EIA) announced that transportation emissions have now surpassed those from electric power generation. Whatever the exact numbers, it's clear that if we want to reduce our GHG emissions we need to work to reduce them from these two sectors.

As individuals we can make choices which help decrease our electricity usage: LEDs over incandescent light bulbs, smart thermostats, etc. If we can afford it, and if we have the right house orientation, we can take an even bigger bite out of our CO2 emissions by installing solar PV panels to produce some or all of our electricity. But to get the biggest bang for our buck, perhaps the single best thing we can do to decrease our emissions is to switch from a normal car (internal combustion engine, or ICE, vehicle) to an all-electric vehicle (EV).

About two years ago my wife and I needed a second car and we decided to buy a 2013 Nissan Leaf. But because we live in Missouri, where most of the electric power is generated by coal, I was concerned that I would just be switching from ICE CO2 emissions to coal-electric emissions. Would we really be making any difference?

To answer that question (and others about how to compare MPG, fuel costs, etc. between a typical ICE and an EV) I kept track of data and made some calculations over a year-long period from September 2015 until August 2016. We bought the Leaf in June 2015 but it took me a few months to come up with a system and get a handle on what information I needed and where to find it.

We have a good grasp of what a gallon of gas means in terms of how much it costs and probably how many miles it will take us in our ICE cars. The "fuel" for an EV is kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity. Comprehending something as amorphous as a kWh stored in my Leaf's battery took a bit of a mental leap for me. The Leaf has a gauge on the instrument panel which displays the battery's amount of charge in 2 kWh increments, which isn't a very fine gauge. But the Leaf also records and uploads information on every trip made: kWh consumed, miles driven, etc. I can access this finer-detailed information from a Nissan website (figure 1). Now that I knew how many miles and how many kWh I used each month, I could look at my monthly electricity bills to see how much the EV "fuel" cost.

Figure 1. Portion of a screenshot of the Nissan Leaf website showing data for August 1, 2016. I travelled 25.1 miles and used 6.2 kWh. The "CO2 Savings" is not very accurate because it doesn't take into consideration the CO2 emissions from the electricity produced to power the car.

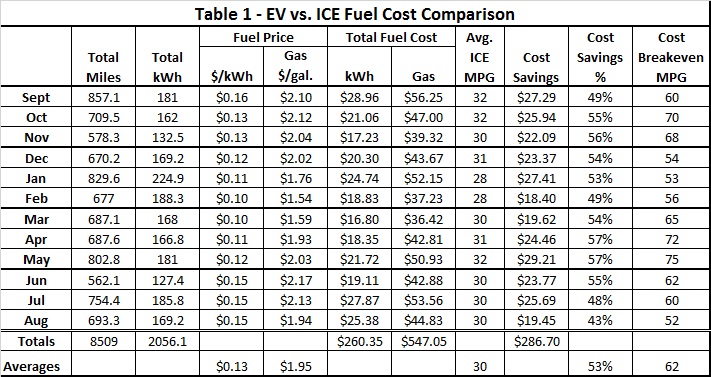

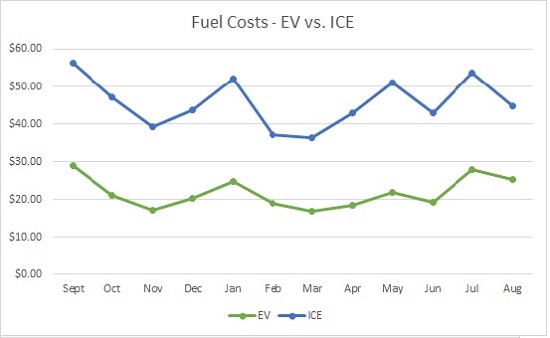

I also kept track of the average gasoline prices during each month and compared those to the electricity costs. Then I asked how would the Leaf compare to an ICE car traveling the same monthly miles. I used my ICE car, a 2009 Ford Escape Hybrid, to make this comparison. The average fuel-economy for the Escape over the year was 30 MPG (range of 28-32 MPG). Table 1 and Figure 2 shows this comparison. For fuel, the cost savings of the Leaf over an ICE vehicle averaged 53%, with a range of 43% to 57% throughout the year. The cumulative savings for the whole year was $287.

Figure 2. Monthly fuel costs for EV (kWh) and an ICE vehicle (gasoline) if driven the same miles as the EV.

In terms of fuel costs, another question was, what MPG would an ICE car need to have to "break-even" with the EV? I calculated this for each month and came up with a range of 52 to 75 MPG, and an average of 62. The only ICE cars on the market which come close to such good gas mileage are hybrid vehicles.

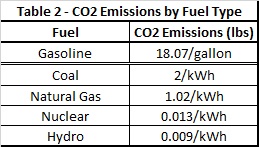

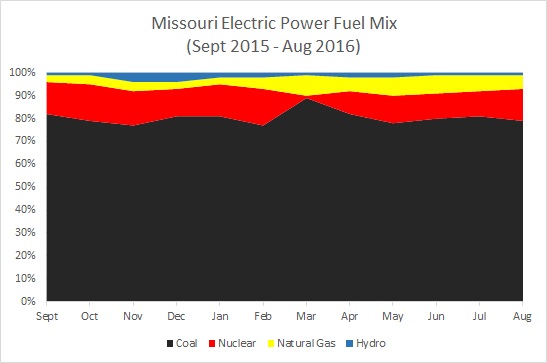

Now I needed to find out the amount of CO2 emissions from each fuel source: gasoline and kWh. Blueskymodel.org gives estimates for emissions from various fuel types (see Table 2). I also needed to find out the fuel mix used in Missouri for electric power generation, which I found in monthly reports from the EIA. Figure 3 below shows the fuel mix used by the larger electric utilities in Missouri throughout the year. Clearly, coal is still king in Missouri, followed by nuclear. However, there are some smaller utilities in Missouri which are beginning to introduce solar and wind to the mix.

Now I needed to find out the amount of CO2 emissions from each fuel source: gasoline and kWh. Blueskymodel.org gives estimates for emissions from various fuel types (see Table 2). I also needed to find out the fuel mix used in Missouri for electric power generation, which I found in monthly reports from the EIA. Figure 3 below shows the fuel mix used by the larger electric utilities in Missouri throughout the year. Clearly, coal is still king in Missouri, followed by nuclear. However, there are some smaller utilities in Missouri which are beginning to introduce solar and wind to the mix.

Figure 3. Fuel mix used by large electric utilities in Missouri, Sept. 2016-Aug. 2017. Coal accounted for an average of 80% of the total fuel mix, Nuclear: 12%, Natural Gas: 6%, and Hydroelectric: 2%.

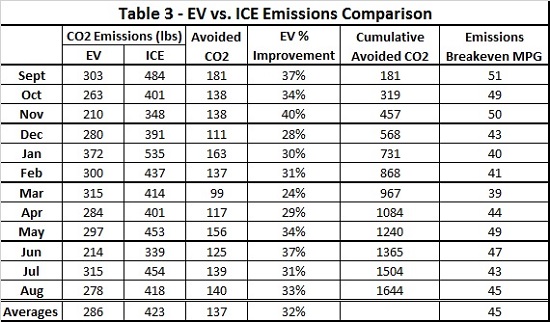

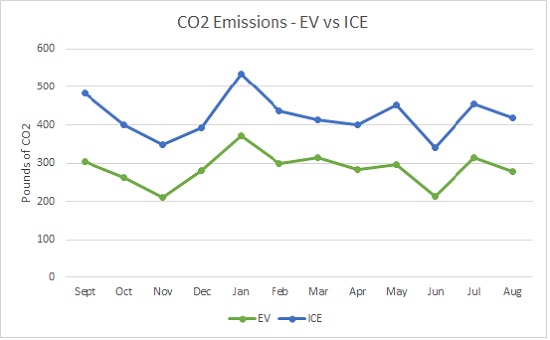

Putting this info together I was able to calculate how many pounds of CO2 my EV was responsible for, and how that would compare to my ICE car. On average, by driving the Leaf, I was able to avoid emitting 137 pounds of CO2 each month, for an average improvement over my ICE car of 32%. For the whole year my avoided CO2 was 1644 pounds, or about ¾ of a metric ton of CO2. See Table 3 and figure 4 for more information.

Figure 4. Monthly CO2 emissions for my EV and an ICE vehicle if driven the same miles as the EV.

Similar to the fuel cost break-even MPG, I also calculated an emissions break-even MPG for each month, in other words, what MPG would an ICE car need to have to break-even with the EV in terms of CO2 emissions. This worked out to a range of 39 to 51 MPG, and an average of 45 MPG. Not as good as the cost comparison but the EV still "emits" less CO2 than most cars on the road.

Missouri has a long way to go to clean-up its electric power generation. But even in such a coal-dependent state, driving an electric car is still "better for the planet" than driving the normal gas car. By shifting to my Leaf I was able to avoid emitting ¾ of a ton of CO2 and I saved $287 on my fuel bill for one year. The extra money is nice, but I'm more concerned about drawing down CO2 emissions. To do that our societies need to switch how we generate power from fossil fuels to renewables. As individuals we can help make that switch by moving from ICE vehicles to EVs. Eventually the electric grid will catch up to us.

Posted by David Kirtley on Thursday, 9 March, 2017

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |