Guest blog post by Lee Tryhorn and Stephen Shaw.

An extremely challenging aspect of present-day climate research is associated with the prediction of regional climate change impacts. That’s what everyone wants to know – how will climate change affect me? People are not directly affected by the global mean temperature. They care about the temperature, rainfall, and wind where they are. This blog post is the first in a series aimed at exploring what the local impacts to climate change might look like in different areas of the globe.

A common sound bite associated with climate change is that with the expected increase in extreme rainfall events, we can expect more flooding. Recent work at Cornell University looking at inland flood risk in New York State suggests that this is not always the case.

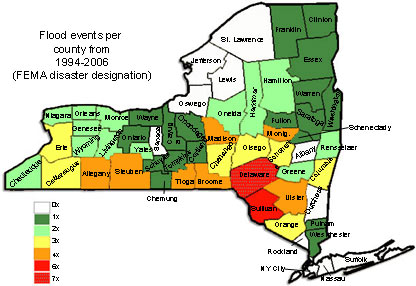

Non-coastal floods occur when rivers or streams overflow, spilling into the adjacent land. This type of flooding is already a huge issue for New York State. Many original settlements were concentrated along rivers, and much of the state’s infrastructure reflects these early patterns of development. From 1994-2006 many regions of the State experienced more than four FEMA-designated flood disasters, with one county experiencing seven! (See Figure 1). Currently, flood damage costs an average of $50 million a year. Consequently, any changes to flooding associated with climate change are of great interest to the people of New York.

Figure 1. Number of FEMA-declared flood disasters in New York counties (Source: compiled from FEMA website).

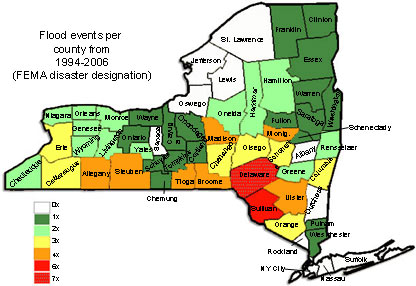

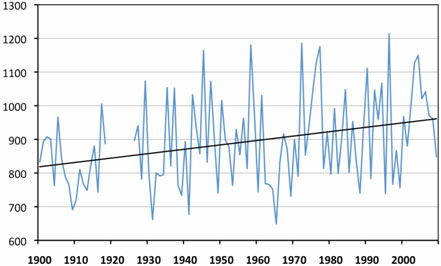

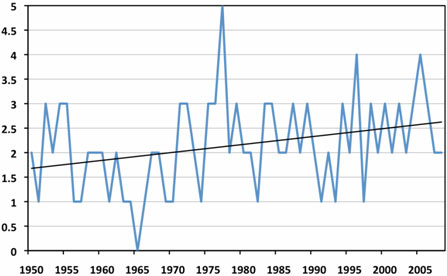

Documented increases in annual rainfall (Figure 2a), as well as higher rainfall intensities (Figure 2b), are often used as justification for predictions of an increased likelihood of flooding. For some parts of the globe, particularly urban areas and those with steep topography, this direct link between precipitation and flooding is quite obvious. Urban areas have impervious surfaces, less vegetation, and compacted soils that minimize the ability of soil to store water. Similarly, areas with very steep slopes are likely to experiences increases in flash floods following increases in rainfall intensity. In these areas, increased precipitation translates directly to increased runoff.

Figure 2a. Annual precipitation (mm) for Ithaca, New York. The figure was created from precipitation data obtained from the Northeast Regional Climate Center.

Figure 2b. Graph of the number of extreme precipitation events (over 50mm in 48 hours) per year in New York State. The figure was created from precipitation data from 46 stations obtained from the Northeast Regional Climate Center.

However, for most of New York State, the picture is more complex.

To better understand flood processes in New York State, linkages between rainfall, streamflow, and snowmelt were examined in three regions of the state. As it turns out, less than 20% of the largest streamflows are actually caused by the largest rain events! (See Table 1). Most of the largest rainfall events in this region occur between May and October. During this time of year, moisture-laden air from the south reaches New York State and often causes two-day rainfall amounts that exceed 125mm. However, these events are usually counteracted by high soil-water storage capacity associated with drier soil conditions and lowered water tables (common during the warmer summer months).

| % Annual Max Discharge Events Occurring When: | |||

| Watershed | 2-Day Annual Max Rainfall | 3-Day Annual Max Snowmelt | May to October |

| Ten Mile River | 15 | 10 | 14 |

| Fall Creek | 20 | 20 | 5 |

| Poultney River | 17 | 9 | 10 |

Table 1. Summary of causative conditions of annual maximum discharges on three watersheds representative of conditions in New York State.

The very largest rainfall events do tend to be associated with the largest flood events, but these rainfall events are often associated with hurricanes or other relatively rare weather patterns that are difficult to accurately predict in the future.

Most (around 60%) of the highest streamflow events in New York result from moderate rainfall events (25-75mm two-day events) on very wet soils (limited rainfall storage capacity). In the future, higher temperatures are likely to dry the soils out due to increased evaporation. So even though the rainfall amounts of the largest storms are likely to increase, the resulting streamflows (and therefore flooding) are uncertain, as there may be a buffering effect from possible increases in soil dryness.

Ultimately, despite the projected increases in extreme rainfall events, it remains uncertain whether flooding will actually increase in New York State with climate change.

New York State is a unique regional situation and it is inappropriate to take a single situation like this and extrapolate it to a global level. This is a common problem in climate science communication. As we further explore climate change impacts at the regional and local level we can expect similar results - that is, a more nuanced, complex picture of change.

These findings are taken from Shaw et al. 2010. Chapter 4: Water Resources. ClimAID: The New York State Adaptation Assessment. This report will be publicly available later this year. A journal article on the same topic is also currently under review.

Posted by ltryhorn on Wednesday, 15 September, 2010

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |