Story of the Week... Analysis of the Week... Editorial of the Week... New SkS Rebuttal Article... El Niño/La Niña Update... Toon of the Week... Graphic of the Week... Photo of the Week... SkS Spotlights... Video of the Week... Coming Soon on SkS... Poster of the Week... SkS Week in Review... 97 Hours of Consensus...

Can Carbon-Dioxide Removal Save the World?

Carbon Engineering, a company owned in part by Bill Gates, has its headquarters on a spit of land that juts into Howe Sound, an hour north of Vancouver. Until recently, the land was a toxic-waste site, and the company’s equipment occupies a long, barnlike building that, for many years, was used to process contaminated water. The offices, inherited from the business that poisoned the site, provide a spectacular view of Mt. Garibaldi, which rises to a snow-covered point, and of the Chief, a granite monolith that’s British Columbia’s answer to El Capitan. To protect the spit against rising sea levels, the local government is planning to cover it with a layer of fill six feet deep. When that’s done, it’s hoping to sell the site for luxury condos.

Adrian Corless, Carbon Engineering’s chief executive, who is fifty-one, is a compact man with dark hair, a square jaw, and a concerned expression. “Do you wear contacts?” he asked, as we were suiting up to enter the barnlike building. If so, I’d have to take extra precautions, because some of the chemicals used in the building could cause the lenses to liquefy and fuse to my eyes.

Inside, pipes snaked along the walls and overhead. The thrum of machinery made it hard to hear. In one corner, what looked like oversized beach bags were filled with what looked like white sand. This, Corless explained over the noise, was limestone—pellets of pure calcium carbonate.

Corless and his team are engaged in a project that falls somewhere between toxic-waste cleanup and alchemy. They’ve devised a process that allows them, in effect, to suck carbon dioxide out of the air. Every day at the plant, roughly a ton of CO2 that had previously floated over Mt. Garibaldi or the Chief is converted into calcium carbonate. The pellets are subsequently heated, and the gas is forced off, to be stored in cannisters. The calcium can then be recovered, and the process run through all over again.

“If we’re successful at building a business around carbon removal, these are trillion-dollar markets,” Corless told me.

Can Carbon-Dioxide Removal Save the World? by Elizabeth Kolbert, Annals of Science, The New Yorker, Nov 20, 2017 Print Edition

Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris agreement means other countries will spend less to fight climate change

The recent round of U.N. climate negotiations ended Friday in Bonn, Germany. While no important decisions were made on climate finance — transfers from wealthy to poor countries to support climate mitigation and adaptation — the question of who pays for global climate gave rise to heated debates.

Formally a technical meeting to finalize the design of the 2015 Paris agreement on climate change, the summit was the first after President Trump’s June 2017 announcement to withdraw from the deal.

Trump’s decision leaves the United States alone outside the Paris agreement. While U.S. noncooperation shouldn’t deter other countries from pledging climate action, my recent research with Thijs Van de Graaf shows that it threatens industrialized countries’ promises of climate finance for mitigation and adaptation in poorer countries.

Trump’s withdrawal from the Paris agreement means other countries will spend less to fight climate change, Analysis by Johannes Urpelainen*, Monkey Cage, Washington Post, Nov 21, 2017

*Johannes Urpelainen is the Prince Sultan bin Abdulaziz Professor of Energy, Resources and Environment at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies. He is also the founding director of the Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy (ISEP).

As climate talks end, it is time for action

It will not go down in history as a great moment of climate diplomacy. But the United Nations climate talks in Bonn, Germany, that ended last week did have their moments. One was the indignant jeering with which audience members and protesters met a White House delegation attempting to justify US President Donald Trump’s take on climate and energy policy. Otherwise, two years after the triumph of reaching the Paris agreement on climate change, delegates were largely preoccupied with the important work of finessing the rules and technicalities of that landmark deal.

As climate talks end, it is time for action, Editorial, Nature, Nov 20, 2017

Climate scientists would make more money in other careers by Dana Nuccitelli, Skeptical Science, Nov 24, 2017

The Australian Bureau of Meteorology issued a La Nina alert Tuesday meaning conditions in the Pacific Ocean have just about reached the point where the weather-roiling phenomena is about to get cracking. But wait, just two weeks ago the U.S. said a La Nina had started. What’s behind the conflicting signals?

It turns out the U.S. and Australia use different criteria to determine when one La Nina milestone is reached. For the U.S., its a drop in sea-surface temperatures of 0.5 degrees Celsius (0.9 Fahrenheit) below the 1981-2010 average. Australia waits for a 0.8 degree Celsius drop from the 1961-1991 average. And though Australia is switching to the newer temperature set, which reflects the warming of the Earth since 1961, it will still wait for a 0.8 degree drop, meaning the U.S., on occasion, will declare a La Nina before their Aussie counterparts.

One Ocean, Two La Nina Forecasts: A Look Behind the Numbers by Brian K Sullivan, Bloomberg News, Nov 21, 2017

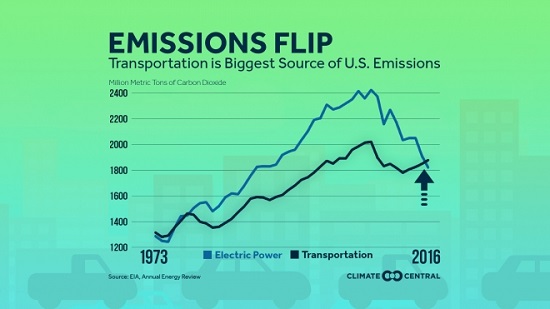

Transportation is the Biggest Source of U.S. Emissions, Climate Central, Nov 21, 2017

Climate change activists march before COP23 United Nations talks

Source: Slide show appended to the article, California's Jerry Brown on how to beat Trump on climate change by Sonya Angelica Diehn, Deutsche Welle/USA Today, Nov 13, 2017

![]()

ISEP – the Initiative for Sustainable Energy Policy – is an interdisciplinary research program that uses cutting-edge social and behavioral science to design, test, and implement better energy policies in emerging economies.

Hosted at the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS), ISEP identifies and pursues opportunities for policy reforms that allow emerging economies to achieve human development at minimal economic and environmental costs. The initiative pursues such opportunities both pro-actively, with continuous policy innovation and bold ideas, and by responding to policymakers’ demands and needs in sustained engagement and dialogue.

A unique feature of ISEP is the pragmatic recognition of the administrative, political, and socio-cultural constraints on policy reform. The initiative is based on the premise that the obstacle to energy policy reform is rarely the lack of better alternatives to the current situation, but rather the vexing difficulty of enacting, implementing, and sustaining these alternatives. We adopt a balanced method that considers both sustainability and access to energy crucial priorities, and conduct rigorous research for evidence-based policy advice.

James Hansen, Pam Peterson, and Philip Duffy join us to discuss how the hesitancy among scientists to express the gravity of our situation is a major block to our understanding and response to climate change, The reticence results from a combination of factors: political pressure, institutional conservatism, the desire to avoid controversy, aspiring to objectivity, etc. But when the data and the conclusions it leads to are alarming, isn't it imperative that the alarm be transmitted publicly? Here is another facet of society's apparent inability to assess and respond appropriately to the present immense, existential threat of climate change.

James Hansen - Scientific Reticence: A Threat to Humanity and Nature, YouTube Video by United Planet Faith & Science Initiative (UPFSI), Nov 19, 2017

Quote derived with author's permission from:

"But our expectations of future warming are not based on extrapolation of recent trends. Rather, we expect climate to be warmer in the future than in the past because we know that greenhouse gases absorb and then re-emit thermal radiation. As people around the world burn more and more fossil fuels, concentrations of greenhouse gases increase, so that solar energy accumulates under the extra absorbing gas. Scientists expect accumulating heat to cause warming temperatures because we know that when we add heat to things, they change their temperatures."

High resolution JPEG (1024 pixels wide)

Posted by John Hartz on Sunday, 26 November, 2017

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |