People are very good at finding ways to believe what we want to believe. Climate change is the perfect example – acceptance of climate science among Americans is strongly related to political ideology. This has exposed humanity’s potentially fatal flaw. Denying an existential threat threatens our existence.

But that’s exactly what many ideological conservatives do. Partisan polarization over climate change has steadily grown over the past two decades. This change can largely be traced to the increasingly fractured and partisan media environment that has created an echo chamber in which people can wrap themselves in the comfort of “alternative facts” (a.k.a spin and lies) that affirm their worldviews. We’ve become too good at fooling ourselves into believing falsehoods, which has ushered in a dangerous “post-truth” era, with no better example than the subject of climate change.

In its December 2017 issue, the Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition published a paper by Stephan Lewandowsky, Ullrich Ecker, and John Cook, along with an impressive 9 responses from other social scientists, essentially investigating how we can make truth great again.

The December 2017 Alabama special election provided an excellent example of the problem at hand. Despite numerous allegations and evidence that Roy Moore pursued and in some cases sexually assaultedteenage girls while in this thirties, 71% of Alabama Republicans believed the allegations were false. Among those disbelieving Republicans, approximately 90% said that the media and Democrats were behind the allegations. As Donald Trump would put it, they believed the allegations were “fake news.” Similarly, 51% of Republicans still believe that Barack Obama was born in Kenya.

It’s understandable that an Alabama Republican would want to believe Roy Moore. We want our representatives to reflect our ideological worldviews. Motivated reasoning and confirmation bias kick in, and partisan media outlets like Breitbart and Fox News provide the material to affirm those biases.

We now have influential partisan media outlets that help people believe what they want to believe, irrespective of factual accuracy. Inconvenient facts are labeled “fake news” and disregarded. In a nutshell, we no longer inhabit a shared reality, and as a result, major problems are going unaddressed because a segment of Americans rejects inconvenient truths.

To solve this dilemma, Lewandowsky and his colleagues propose what they call “technocognition,” which is described as:

the idea that we should use what we know about psychology to design technology in a way that minimizes the impact of misinformation. By improving how people communicate, they hope, we can improve the quality of the information shared.

The authors propose a number of ideas to help bring an end the post-truth era. One key idea involves the establishment of an international non-governmental organization that would create a rating system for disinformation. There are already some similar examples in existence – Climate Feedback consults climate scientists to rate the accuracy of media articles on climate change, and Snopes is a widely-respected fact checker. The challenge would of course be to convince conservatives to accept a neutral arbiter of facts, and continue accepting it when information they want to believe is ruled inaccurate.

These independent rulings could then be conveyed via technology. For example, Facebook could flag an article that’s based on false information as an unreliable source, and Google could give more weight in returning factually accurate news and information at the top of its search results lists.

The study authors also suggest that inoculation theory techniques could help dislodge misinformation after it first takes hold. This involves explaining the logical fallacy underpinning a myth. People don’t like being tricked, and research has shown that when they learn that an ideologically-friendly article has misinformed them by using fake experts, for example, they’re more likely to reject the misinformation.

The authors also encourage teaching people – particularly students – how to identify misinformation techniques and the other strategies used to create the partisan echo chamber. Younger Americans are already less susceptible to the conservative media bubble. The median age of primetime Fox News viewers is 68, and Alabamans under the age of 45 voted for Roy Moore’s opponent Doug Jones by a 23-point margin. Teaching them how to identify misinformation techniques will help inoculate younger Americans against the corrosive effects of the partisan media bubble.

However, in their follow-up paper addressing and summarizing the 9 responses to their original study, the authors note that technocognition faces one additional major obstacle:

This obstacle is the gorilla in the room: Policy making in the United States is largely independent of the public’s wishes but serves the interests of economic elites.

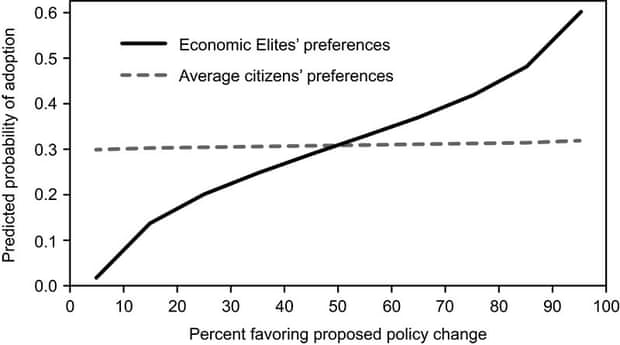

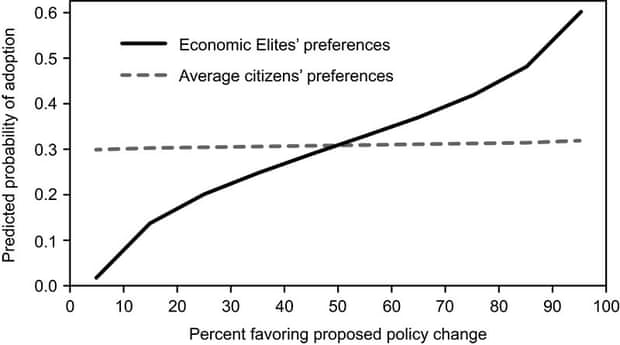

To illustrate this point, they plot data from a 2014 study by Martin Gilens and Benjamin Page. The study concluded:

When a majority of citizens disagrees with economic elites and/or with organized interests, they generally lose. Moreover, because of the strong status quo bias built into the U.S. political system, even when fairly large majorities of Americans favor policy change, they generally do not get it…we believe that if policymaking is dominated by powerful business organizations and a small number of affluent Americans, then America’s claims to being a democratic society are seriously threatened.

Data on correlations between public opinion/economic elites’ preferences and odds of a policy being implemented, from Gilens & Page (2014). Illustration: Lewandowski et al. (2017), Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition

The study found that while economic elites’ and business groups’ preferences often result in policy changes, public opinion has virtually no influence on policy outcomes. We see this all the time on issues from climate change to gun control, and in the recent examples of Obamacare (+12% approval but just one vote shy of Republican repeal) and the tax plan (-14% approval but passed by Republicans in Congress). This means it will be difficult to implement policies to shift us away from our current post-fact and post-truth world unless elites or interest groups or policymakers decide it’s in their best interest.

Posted by dana1981 on Wednesday, 27 December, 2017

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |