Government estimates show U.S. fossil fuel use will fall sharply in April, while renewables are on the upswing.

Government estimates show U.S. fossil fuel use will fall sharply in April, while renewables are on the upswing.This is a re-post from Yale Climate Connections by Karin Kirk

A banner on the International Energy Agency website spells it out in bold font: “The global oil industry is experiencing a shock like no other in its history.”

As the response to the coronavirus pandemic upends the lives of billions of people, the world’s thirst for oil is undergoing an uncharacteristic lull. The IEA analysis describes ripple effects through the entire industry: “As demand plummets, the entire supply chain of oil refining, freight, and storage is starting to seize up.”

Not even the most wildly optimistic climate activist could have imagined the way fossil fuel use has fallen off a cliff in recent weeks. But profound human suffering, widespread economic hardship, and amplified inequity and injustice underlie the ebb in energy use. This is far removed from a situation that merits celebration. However, there are questions to examine in light of an unanticipated, unintentional, and likely temporary lapse in carbon emissions.

For example, how does the current downturn in fossil fuel use compare to what’s needed to put the world on track to avoid the most severe effects of climate change? As we proceed down a decades-long path to a fossil fuel phase-out, at what point would emissions have to be limited to right where they are currently – but permanently rather than temporarily?

Here’s a back-of-the-envelope calculation that breaks down those questions, but with the caveat that this is entirely based on projections and estimates, many of which are changing daily. This is not an emissions inventory or a prediction of the future. That said, the profound and near-instant dropoff of fossil fuel consumption allows for an unusual opportunity to examine carbon emissions in a new light.

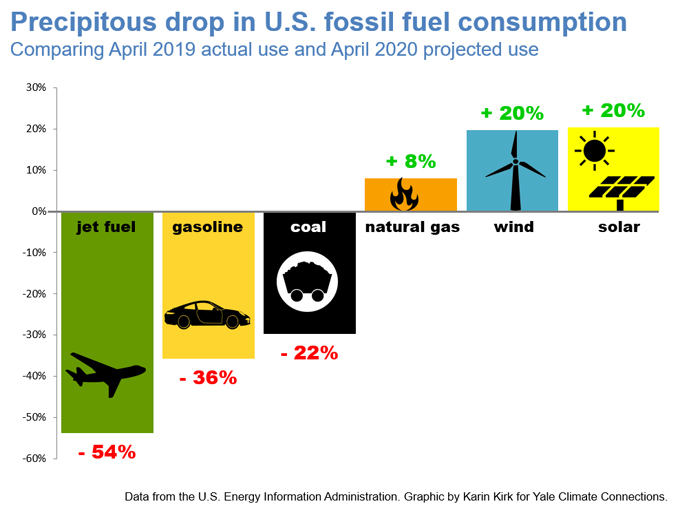

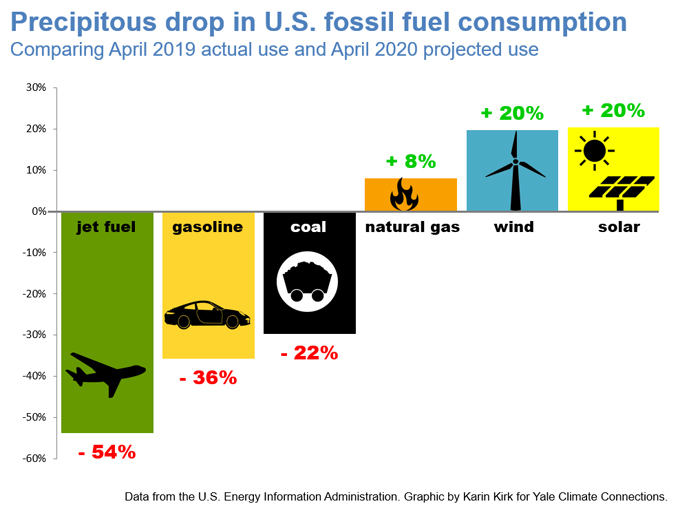

The slump in American fossil fuel use can be seen in EIA’s Short-Term Energy Outlook.

Government estimates show U.S. fossil fuel use will fall sharply in April, while renewables are on the upswing.

Government estimates show U.S. fossil fuel use will fall sharply in April, while renewables are on the upswing.

For April 2020, consumption of aviation fuel is expected to drop by 54% compared to April 2019, as the flow of U.S. air travel passengers has declined by 96%.

Americans’ love affair with cars will be largely unrequited this month, as gasoline consumption will sink by 36%, reaching its lowest level in three decades (while also contributing to cleaner air and fewer car accidents).

Taken altogether the EIA anticipates a 22% slowdown across all liquid petroleum fuels, which includes gasoline, diesel, jet fuel, and fuel oil.

The fuels comprising that 22% slowdown account for 45% of all energy-related emissions in the U.S.

Coal has suffered a double whammy. The use of coal for electricity generation was already in an unrecoverable dive because it’s among the most expensive ways to generate electricity. As peak electricity use shrinks, the most expensive parts of the portfolio are the first to be shut off, suppressing coal even further. An EIA analysis explains, “The forecast for lower overall electricity demand leads to an expected decline in fossil-fuel generation, especially at coal-fired power plants.”

EIA is projecting a 30% reduction in coal use compared to this time last year.

Natural gas has been taking up the slack in coal’s wake, and gas use has been steadily rising for a decade. Consumption of natural gas shows little change from pre-coronavirus restrictions and is forecast to increase by 8% in April compared to 2019.

Irrespective of the coronavirus pandemic, both wind and solar are enjoying strong upward trends, largely the result of ongoing additions of new generating capacity. April’s output of wind and solar energy are each expected to increase by 20% compared to a year ago. But the pandemic is playing some role: With lower electricity demand overall, utilities can primarily rely on the cheapest resources – wind and solar.

Compared to electricity use in 2019, this month’s electricity consumption is predicted to drop by 2%.

Across all sectors and all forms of energy, U.S. total energy use in April 2020 is likely to fall by 11% from levels in April 2019.

Rystad Energy projected that global oil demand will slacken by 27.5% in April, while Trafigura analysts estimated the decline at around one-third.

China’s appetite for oil dropped by 35% in the depths of the COVID-19 outbreak, and in India oil consumption is sagging by as much as 70% while the country is under national lockdown.

Note that total fossil fuel emissions are from coal, oil, natural gas, and cement, so a 35% reduction in oil consumption doesn’t equate to a 35% cut in overall emissions. Liquid hydrocarbons are the hardest-hit by coronavirus restrictions because those are the fuels used for transportation. Electricity demand is also falling, but not as much as use for transportation.

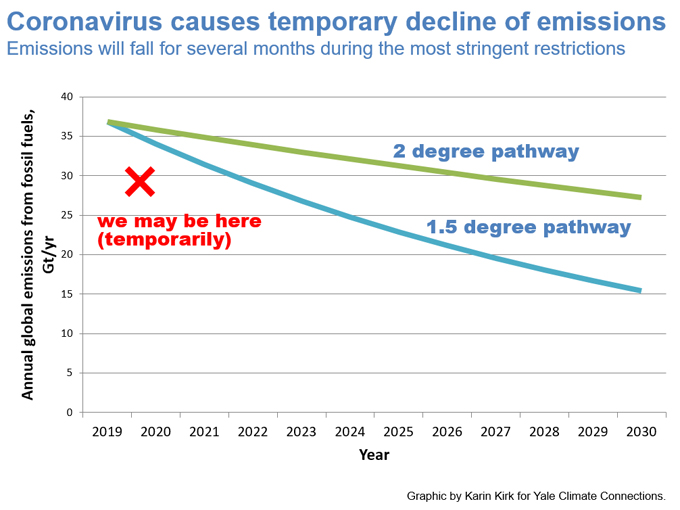

It’s clear that these reductions will be temporary, although analysts are hard pressed to predict when things will rebound. Nonetheless, the situation offers a glimpse of a lower-emissions future. What does this spring’s astonishing downtrend in consumption of fossil fuels look like when plotted against various emissions reduction pathways?

First, one can look at energy curtailment during peak-COVID-19 periods around the world, when each nation hit its maximum reductions. This approach would illustrate the deepest cuts in emissions, albeit the shortest-lived.

In the absence of estimates of worldwide emissions on a month-by-month scale, a few numbers can be used as guidance. CarbonBrief has estimated that China’s emissions temporarily fell by 25% in February. Using very rough math on the EIA’s projections for April yields a 15% reduction in energy-related emissions for the month. Europe is undergoing a significant decrease in energy demand, and one modeling scenario estimated a 24% drop in E.U. emissions.

Even though no firm number can be pinned down, for the sake of argument one can plot a temporary global reduction in fossil fuel use of 20% and see where that sits on decarbonization curves. Would that be enough to get us ahead of the game?

The U.N.’s 2019 Emissions Gap Report concluded that greenhouse gas emissions will need to fall by 7.5% per year every year from now until 2030 to stay within the “aspirational” 1.5-degree Celsius target. To remain below the 2-degree Celsius threshold, emissions would need to decrease by 2.7% per year.

A very rough estimate of emissions reductions during peak Covid-19 restrictions.

A very rough estimate of emissions reductions during peak Covid-19 restrictions.

Looking first at the 1.5-degree pathway, April 2020’s emissions fall below the target – for now. To stay on track, this reduction would have to become permanent by 2022, and then continue to decline. Take stock of the idle airplanes, the empty roadways, and imagine reaching that same level of decarbonization – and then some – in just two years. Of course, emissions reductions aren’t achieved by simply halting productivity and transportation, but by shifting them to cleaner means. Nonetheless, this exercise in mathematics offers a sense of the scale of change needed in a vanishingly short time frame.

Backing off to the 2-degree target, we’d have until 2028 to make today’s cuts permanent. That strategy may feel to some a bit more doable, but it still would require ambitious and relentless progress toward decarbonization across all sectors of the global economy.

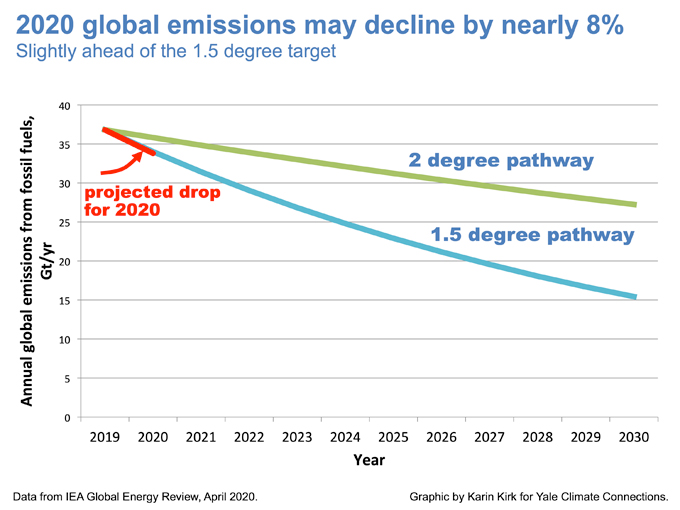

Looking at the expected emissions for all of 2020, rather than just this spring, a few estimates are beginning to emerge.

The EIA forecasts a 7.5% drop in energy-related emissions in 2020 for the U.S. alone. CarbonBrief estimated global emissions could fall by about 5.5% for the year. Rob Jackson, chair of the Global Carbon Project, is anticipating a decline of 5% or more. Meanwhile, Rystad Energy has projected a 9.4% reduction in global oil demand this year.

A report from the International Energy Agency released mere hours after this article was published offered a revised estimate of an 8% drop in global emissions for 2020. The figure below has been updated to show an 8% reduction in emissions, rather than a 5.5% decline as was originally plotted.

Global emissions may decline by around 8% this year, which is consistent with the pathway needed to limit climate warming to 1.5 degrees.

Global emissions may decline by around 8% this year, which is consistent with the pathway needed to limit climate warming to 1.5 degrees.

Those numbers put the world slightly ahead of the 1.5-degree pathway. But as the IEA report says, “the historic decline in global emissions is absolutely nothing to cheer,” as the fall in energy use is underlain by human suffering and economic turmoil felt across the world.

Even with these temporary reductions, there’s the major caveat that the world would have to sustain this same level of emissions reductions every year. That’s unlikely, of course. At some point coronavirus restrictions will be lifted, offices will flicker back to life, and roadways will fill up once again as people resume some version of the busy, polluting lives they previously led. Economic stimulus initiatives will stoke industrial and commercial productivity, and if oil prices remain low, energy use could be further amplified.

Case in point: China has already ramped up fossil fuel consumption, and coal-burning power plants have rebounded back to within a normal range. The EIA expects 3.6% growth in U.S. energy-related emissions in 2021, knocking us off course once again.

Much has been written about how the pandemic offers opportunities for green investments, a moment to re-think spur-of-the-moment travel, and a once-in-a-generation opportunity to pause and take stock on the human condition. At the same time, as the skies are clear and the highways whisper-quiet, we also gain a brief window to a world with less pollution, allowing one to imagine what it might take to bend the curve, permanently, toward meaningful improvement.

Posted by Guest Author on Friday, 29 May, 2020

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |