Wind and solar are 30-50% cheaper than thought, admits UK government

This is a re-post from Carbon Brief by Simon Evans

Electricity generated from wind and solar is 30-50% cheaper than previously thought, according to newly published UK government figures.

The new estimates of the “levelised cost” of electricity, published this week by the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS), show that renewables are much cheaper than expected in the previous iteration of the report, published in 2016.

The previously published version had, in turn, already trimmed the cost of wind and solar by up to 30%. As a result, electricity from onshore wind or solar could be supplied in 2025 at half the cost of gas-fired power, the new estimates suggest.

The new report is the government’s first public admission of the dramatic reductions in renewable costs in recent years. It had previously carried out internal updates to its cost estimates, in both 2018 and 2019, but these were never published despite repeated questions in parliament.

The BEIS report also presents new estimates of the “enhanced levelised cost” of different technologies, which reflects any wider system benefits and their “system integration costs”.

These alternative figures, which have been under development for several years, put gas with carbon capture and storage (CCS) in a particularly favourable light, with costs comparable to wind or solar. CCS is expected to feature in the upcoming energy white paper, due this autumn.

Levelised cost

The new BEIS report on electricity generation costs is the first to be published in nearly four years. It sets out estimates of the “levelised cost of electricity” (LCOE) for various technologies, ranging from unabated gas-fired power stations through to wind, solar and gas CCS.

LCOE estimates are presented as the average cost of electricity, per megawatt hour (MWh) generated, across the lifetime of a new power plant. The new report gives these figures in £(2018). (Where comparisons are made, Carbon Brief has adjusted earlier estimates in line with inflation.)

The LCOE is designed to offer uniform cost comparisons between technologies, based on a consistent framework and a series of assumptions. These include how much power plants cost to build and their average electricity output each year, as well as project lifetimes and financing costs.

The LCOE does not include wider costs and benefits at a system level. This could include reductions in wholesale prices due to abundant zero-carbon generation, or higher grid costs due to the variable output from wind and solar.

The latest BEIS report gives LCOE estimates for projects that start operating in 2025, 2030, 2035 or 2040. Changes over time result from “technological learning”, as well as future prices for fossil fuels and CO2 emissions. For the first time, the report also presents “enhanced levelised cost” estimates. These attempt to capture wider costs and benefits, and are discussed below.

The BEIS estimates are updated at regular intervals, with previous iterations having been published in 2016, 2013, 2012, 2011 and 2010. The department made internal updates in 2018 and 2019, with these revisions the subject of peer review papers also published this week.

However, the 2018 and 2019 updates remain unpublished, despite numerous questions in parliament in which MPs asked repeatedly after the latest BEIS cost estimates.

Renewable costs slashed again

The most striking result of the new 2020 report is that BEIS has once again slashed its estimates for the levelised cost of wind and solar power. This is illustrated in the chart, below.

In 2013, the UK government estimated that an offshore windfarm opening in 2025 would generate electricity for £140/MWh. By 2016, this was revised down by 24%, to £107/MWh. The latest estimate puts the cost at just £57/MWh, another 47% reduction (leftmost red column, below).

The new estimates include similarly dramatic reductions for onshore wind and solar, with levelised costs in 2025 now thought to be some 50% lower than expected by the 2013 government report.

In contrast, the new report does not revise earlier estimates for the cost of nuclear power. Instead, BEIS notes the government’s “ambition” that nuclear should deliver a 30% cost reduction by 2030.

Levelised cost estimates for electricity generation in 2025, in £(2018) per megawatt hour, for a range of different technologies. For each technology, estimates were published in 2013 (dark grey), 2016 (light grey) and 2020 (red). Source: Carbon Brief analysis of BEIS estimates adjusted for inflation using Treasury deflators. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

The reasons for the renewable cost reductions are well documented. They include technological learning in the industry – with larger, more efficient manufacturing plants for solar and larger turbines for wind – but also operational experience, longer project lifetimes and cheaper finance.

The reductions have already been reflected in auctions for UK government contracts. Most recently, contracts were awarded for offshore windfarms due to start operating in the mid-2020s, at prices below the costs of existing gas-fired power stations – making them effectively “subsidy free”.

The levelised costs published by BEIS are a slightly different measure to the “strike prices” awarded under these government “contracts for difference”. The central estimate of £57/MWh LCOE for offshore wind in 2025 is higher than strike prices of £44/MWh awarded at auction.

According to BEIS, the difference is partly explained by winning project bids having particularly favourable site conditions, as well larger sizes that bring economies of scale.

Wind and solar cheapest

The new BEIS estimates make another small reduction in the levelised cost of electricity from gas, attributable to the department assuming turbines are now slightly more efficient.

Despite this small reduction, the much larger cuts for renewables mean onshore wind and solar are now expected to be half as costly as gas in 2025, as shown in the chart below.

Notably, the BEIS cost estimates for onshore wind and solar assume no access to government contracts, meaning higher borrowing costs and an increased LCOE. Since these technologies will now once again be able to bid for contracts, their costs will be even lower than presented here.

Carbon Brief estimates using a basic LCOE calculator and 2018 BEIS figures for financing costs, with or without a government contract, suggest around £2/MWh could be shaved off onshore wind and solar prices, based on a 0.8 percentage point reduction in the cost of capital.

Levelised cost estimates for electricity generation in 2025, in £(2018) per megawatt hour, for a range of different technologies. For each technology, the bars show the range of uncertainty for construction and borrowing costs, while the whiskers show uncertain fuel prices. Source: Carbon Brief analysis of BEIS estimates adjusted for inflation using Treasury deflators. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

BEIS has also significantly reduced its levelised cost estimates for gas CCS, meaning the technology is seen as competitive with unabated gas in 2025 and cheaper thereafter, as the price of emitting CO2 rises (see chart below).

The department explains this reduction by pointing to assumptions of more rapid CCS construction timelines and higher associated gas turbine efficiency, along with lower estimates for the cost of CO2 transport and storage. These changes are based on a 2018 report for government.

The levelised cost reduction for CCS also relates to an assumption that financing costs will be much lower – by at least 2 percentage points – than thought in the 2016 estimates. Given the technology has yet to be deployed at scale in the UK, this assumption is highly uncertain.

Offshore wind to overtake onshore

The BEIS estimates show that wind and solar will continue to get cheaper over time as larger turbines are deployed and other sources of learning continue.

This is shown in the chart below, including the notable fact that BEIS now expects offshore wind to become cheaper than onshore by the mid-2030s. This is primarily due to much larger turbine sizes, reaching 20 megawatts (MW) by 2040, up from 9MW today.

Levelised cost estimates for electricity generation in 2025-2040, in £(2018) per megawatt hour, for a range of different technologies. For each technology, the lines show expected changes in cost over time. Source: Carbon Brief analysis of BEIS estimates adjusted for inflation using Treasury deflators. Chart by Carbon Brief using Highcharts.

Larger turbines placed further out to sea give access to stronger and much more consistent winds, meaning offshore windfarms are expected to have “load factors” reaching as high as 63% in 2040.

Load factors represent the proportion of theoretical maximum electricity output achieved across an entire year, after accounting for variations due to maintenance and weather conditions. For reference, the average load factor for the world’s coal-fired power stations is now around 50%.

In the chart above, note that the rising cost of gas-fired electricity is due to an assumption that CO2 prices will continue to increase over time.

Whole system costs

Wind and solar are the clear winners of the new BEIS estimates, expected to be able to generate electricity much more cheaply than any other technologies.

However, the report also publishes estimates of the “enhanced levelised cost” of each source of electricity, which it says “changes our cost perception of different technologies”. The department started work on this area in 2015 and has only now published its findings for the first time.

This work is an attempt to capture the “whole system costs” of an individual power plant. This could include the costs of enhancing the electricity network to connect a new power station, balancing supply and demand in real time, and providing backup power during periods of low wind or sun.

(See Carbon Brief’s 2017 article on system costs for more background.)

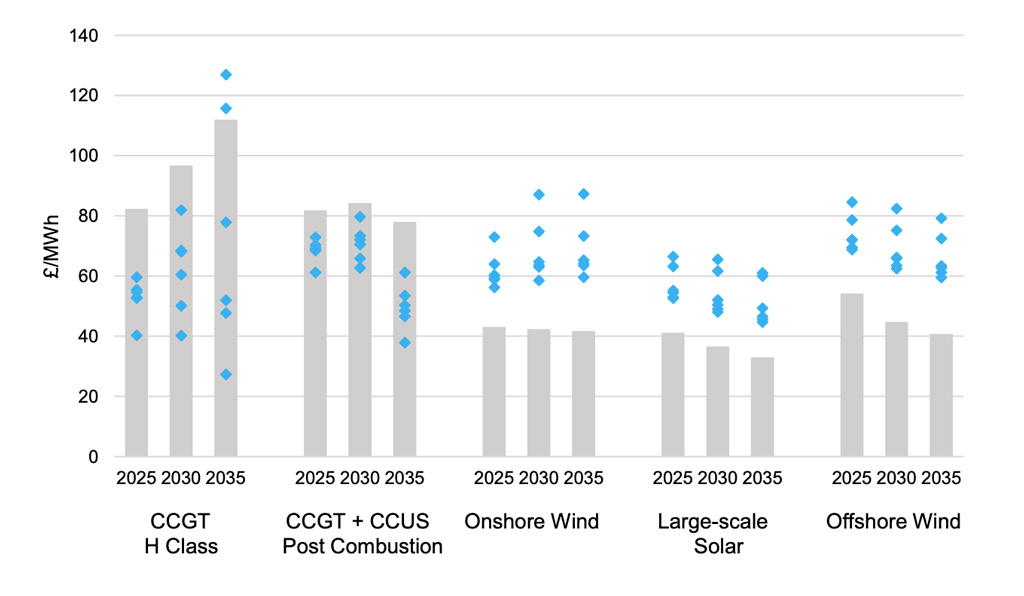

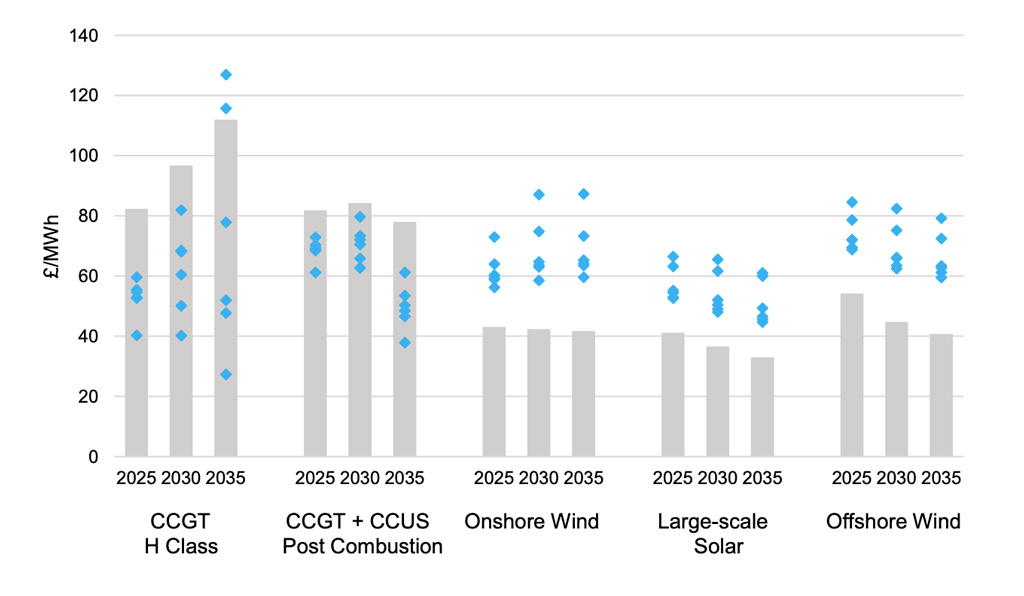

The BEIS estimates of these enhanced levelised costs are shown in the chart below, for each technology in 2025, 2030 and 2035. The grey bars represent the standard LCOE and the blue diamonds show the “enhanced” estimate under six different scenarios.

In general, gas and gas+CCS have “enhanced” costs that are lower than their respective LCOEs, whereas renewables are higher. Overall, the chart shows that enhanced cost estimates are in a similar ballpark across the different technologies.

Enhanced levelised cost estimates for electricity generation in 2025-2035, in £(2018) per megawatt hour, for a range of different technologies. For each technology, the grey bars show the levelised cost and the blue diamonds show enhanced levelised costs in six scenarios, which vary as to the characteristics of the overall electricity system. Source: BEIS 2020.

It is difficult to go beyond a broad interpretation of these new estimates, however, because they span a very wide range of cost figures.

Dr Rob Gross, director of the UK Energy Research Centre (UKERC), tells Carbon Brief that system costs are not fixed, as they depend strongly on the characteristics of the system.

As a result, Gross says “it is particularly important for assumptions to be explicit” and that numbers presented without such transparency run the risk of being “misleading”.

Dr Phil Heptonstall is research fellow at Imperial College London and a co-author, with Gross, of a 2017 review of system cost estimates for renewables. He tells Carbon Brief:

“You can come up with quite a high number if you assume that you make no attempt to make the system more flexible. But that’s not a rational or sensible thing to do.”

The lack of transparency about the assumptions in the BEIS report is “frustrating”, Heptonstall adds, and makes it “difficult to form any conclusions about what it means”.

Notably, the BEIS report does not set out its assumptions around the makeup of the overall system, within which the “enhanced levelised cost” estimates are being made.

All it says is that the six scenarios shown in the chart represent higher or lower electricity demand, combined with three pathways towards net-zero in 2050, using high shares of renewables, high nuclear or a “balanced” mix of the two.

However, key assumptions around the assumed levels of flexibility of the electricity system are not disclosed by BEIS. Flexibility could include greater levels of interconnection with other countries, higher deployment of battery storage or enhanced use of electric vehicle “smart charging”.

A report from the Committee on Climate Change (CCC) shows that system costs depend very strongly on flexibility. For offshore wind, for example, integration costs range from less than £10/MWh to £50/MWh, with the high end representing no progress over current levels of flexibility.

The BEIS report includes system costs in the range of around £12-30/MWh in 2025 rising to around £20-40/MWh in 2040. Heptonstall tells Carbon Brief:

“If we don’t know what types of flexibility is provided in those scenarios, we can’t tell if those numbers are a fair reflection.”

Carbon Brief has asked BEIS to explain its assumptions on flexibility. This article will be updated, if a response is received.

Posted by Guest Author on Monday, 21 September, 2020