Science and its Pretenders: Pseudoscience and Science Denial

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public.

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public.

The human brain is a fascinating thing. It’s capable of great things, from composing symphonies to sending people to the moon. Its ability to learn and problem solve is truly awe-inspiring.

But the brain is also capable of Olympic-level self-deception. When it wants something to be true, it masterfully searches for evidence to justify the belief. And when it doesn’t want to believe, its ability to deny or discount evidence is (unfortunately) unsurpassed.

In humanity’s search to understand the world around us, the invention of science was revolutionary. No more relying on our flawed perceptions and irrational thinking. Finally, there was a way of knowing that demanded evidence and made a systematic attempt to identify and minimize our biases. The proof was in the results: we owe much of the increase in the quality and quantity of our lives over the last century to scientific advancements.

It’s no wonder then that people trust science. Unfortunately, many don’t understand how science works and what makes it reliable, leaving people vulnerable to assertions that seem scientific… but aren’t. Charlatans who seek to elevate their claims dress them up in the trappings of science to fool those with worldviews that align with their goals. They know full well that we are most likely to fall for misinformation when we want…or don’t want…to believe.

Making good decisions requires good thinking and the ability to identify the misuse of science to justify our beliefs. We don’t want to be fooled by science’s pretenders.

Science is a reliable way of knowing

To understand what science isn’t, we have to first understand what it is.

And like most things in life, it’s complicated.

Unlike how science is often taught in school, there is no single, recipe-like scientific method. At its core, science is a community of experts using diverse methods to gather evidence and scrutinize claims. It’s a way of learning about the natural world, of trying to get closer to the truth by testing explanations against reality and critically scrutinizing the evidence.

Science is reliable because the process is designed to minimize the impact of our biases and root out errors or fraud. Scientists must follow the evidence wherever it leads, regardless of their beliefs or biases. It’s human nature to want to confirm our pet hypotheses, but the ability to find supporting evidence doesn’t make them true. Instead, scientists set out to disprove their explanations, and when they can’t, they accept them. Before their study can be published in the scientific literature, it must pass peer review, in which other experts critically scrutinize their work.

A critical foundation of science is skepticism, which is simply insisting on evidence before accepting a claim. Scientists are open to all claims, but proportion their acceptance to the strength and quality of the evidence.

Scientific conclusions are always tentative. Each study is a piece of a larger puzzle that becomes more clear when more pieces are put into place. Science doesn’t provide absolute certainty, but instead reduces uncertainty as evidence accumulates. But there’s always the possibility that we’re wrong, so we should leave ourselves open to changing our minds with new evidence.

Importantly, science is a community effort, providing a system of checks and balances on the process that helps to correct for biases and identify errors and fraud.

Is science perfect? No. But it’s better than the alternatives.

Which brings me to….

Science’s pretenders don’t play by science’s rules

If humans are masters at self-deception, science’s pretenders are our enablers. By disguising our desired beliefs in the trappings of science, we are able to convince ourselves (and others) that our conclusions are justified.

We don’t set out to fool ourselves, of course. But our beliefs are important to us: they become part of who we are and bind us to others in our social groups. So when we’re faced with evidence that threatens a deeply-held belief, especially one that is central to our identity or worldview, we engage in motivated reasoning and confirmation bias to search for evidence that supports the conclusion we want to believe and discount evidence that doesn’t.

The key difference between science and its pretenders is this: Whereas science is an objective search to understand and explain the natural world, science’s pretenders are motivated by their desire to protect cherished beliefs.

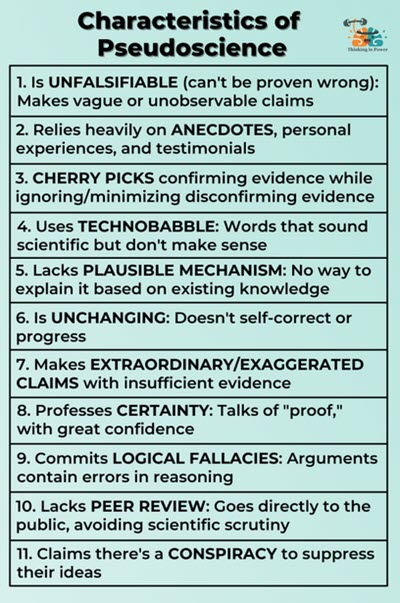

To accomplish this goal, science’s pretenders break many of the rules that make science reliable. Instead of following evidence to a conclusion, science’s pretenders work backwards, searching through the body of evidence for the pieces they can cherry pick to make their case. Rather than minimizing biases and identifying errors, the pretender community is hostile towards legitimate criticism, even viewing it as a conspiracy. In fact, the pretenders require believing in a grand conspiracy perpetuated by the entire scientific community. Why else would nearly all scientists reject your claims? And while science is always tentative and willing to change with evidence, the pretenders are absolutely certain they’re right. If the evidence available today isn’t enough to change their mind, why would it be any different in the future?

While all of science’s pretenders portray themselves as scientific while failing to adhere to science’s methods, the two major types of pretenders have key differences.

Science denial is the refusal to accept well-established science. Essentially, denial suggests that the expert consensus is wrong by focusing on minor uncertainties and engaging in conspiracy theories to undermine robust science. Denial is motivated by not wanting to believe a scientific conclusion, often because it conflicts with existing beliefs, identity or vested interests.

Industry-funded denial campaigns from the tobacco industry, for example, manufactured doubt about the link between smoking and health problems to prevent government regulation. Fossil fuel companies used the same strategy, with many of the same think tanks and scientists, to convince the public that the science of human-caused climate change wasn’t “settled,” even though their own scientists made the same connections.

Denialists don’t want to believe, so they attack science using one of its most essential characteristics – that science never proves with 100% certainty. They know that people don’t understand how the process of science works. They tell the public that “it’s only a theory,” even though a scientific theory is the pinnacle of certainty in science. Or they say “science hasn’t proven” something, ignoring the fact that science never proves.

Many denialists unfortunately believe they are the true “skeptics” who are embracing science’s rigor. They claim they want evidence, but they’ve set an impossibly high standard that can never be achieved. Failure to accept well-supported conclusions in the light of overwhelming evidence isn’t skepticism. It’s denial.

Pseudoscience is the promotion of a non-scientific “theory.” Basically, pseudoscience promotes unsupported, false, or even unfalsifiable claims as scientific by dressing them up as science. Pseudoscientific beliefs are motivated by wanting to believe a non-scientific conclusion, often due to existing beliefs, identity or wishful thinking.

Alternative medicine, the health/wellness industry, and the New Age movement are just a few of the many areas that promote pseudoscientific claims. Pseudoscience plays on our biases, appeals to our desires, and offers false hope. It would be fascinating if the stars could predict our future, or if a mysterious human-like creature lived wild in the mountains. And we know our healthcare system has problems, so “natural” and “ancient” cures offer enticing – although ineffective – alternatives.

Pseudoscientists want to believe, so their standard of evidence to support their beliefs is very low. Anecdotes are widely used, even though science knows that we can easily be misled by our personal experiences. Claims are often so vague that nearly any evidence could be interpreted as supporting them. Studies that are so poorly designed they can’t pass peer review are instead published in their own journals that lack critical scrutiny.

Many who believe in pseudoscience claim scientists won’t accept their conclusions because they are too skeptical, or conspiring against them. But the process of science is designed to challenge ideas, not confirm them. Criticism is expected…encouraged even. Pseudoscientists are so sure they’re right, and their desire to believe is so strong, that they are unable to objectively evaluate their own claims.

Those who promote pseudoscience can be excellent marketers, skillfully convincing those who want to believe without using reliable evidence. If their claims were scientific they would certainly sell it as such. But that’s why it’s pseudoscience.

Example: Evolutionary theory, evolution denial, and creationism

There’s perhaps no theory more important to science, and yet more misunderstood by the public, than evolution.

Scientific theories are explanations supported by vast amounts of evidence. Scientists use theories to make predictions for further testing, the results of which either strengthen the theory or suggest the need to modify it. Over time, experts begin to agree that there’s enough evidence to accept the explanation. This is the process of science in action.

The term theory is the source of much confusion for most people, however, who use it to mean “guess.” But while science doesn’t prove explanations, theories are as close as science can get. In fact, the ultimate goal of science is to understand and explain natural phenomena with theories. Other theories include gravitational theory, cell theory, germ theory, molecular theory, gene theory…..

Evolutionary theory is the single most important theory in all of the life sciences. It essentially states that all species alive today have a common ancestor. It helps to explain the similarity of living organisms as well as their diversity: more related populations are more similar and less related populations less similar. Evidence for evolution comes from many diverse lines, including anatomical similarities, shared developmental pathways, vestigial structures, imperfect adaptations, DNA and protein similarities, biogeography, fossils, etc. There are certainly details left to work out, but the basis of evolutionary theory is so well supported that the plausibility of it being found to have serious flaws is next to zero.

So, the science is clear, living things have evolved. The evidence agrees and so do the experts. As Theodosius Dobzhandky explained, “Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution.”

Unfortunately, there are many who do not want to accept that living things evolved, viewing it as a threat to their religious beliefs. And motivated reasoning is a powerful thing.

The desire to not believe leads to denial. Evolution “is just a theory,” and “isn’t settled science.” Impossibly high standards of proof are demanded and minor uncertainties used to try to bring down the whole theory.

The desire to want to believe in a religious explanation fuels the pseudoscience of creationism. An important characteristic of science is that it must be falsifiable, and since there is no conceivable way to test for a supernatural creator, creationism is not science. Even more, there simply isn’t evidence to support the idea that living things were created in their current form only a few thousand years ago.

Both evolution denial and creationism work backwards from their desired conclusion. Both cherry pick evidence and ignore or discount disconfirming evidence. Both are overly confident they’re right and unwilling to objectively evaluate the body of evidence and change their mind.

And both accuse scientists of conspiring against them. Why else would nearly all experts reject their claims?

However, this conspiracy would require the cooperation of botanists, zoologists, cytologists, microbiologists, molecular biologists, geneticists, paleontologists, etc…from nearly every academic institution, government agency, and industry…and in nearly every country on earth.

This assertion fundamentally misunderstands science’s incentive structure: the best way to make a name for yourself as a scientist is to discover something previously unknown or to disprove a longstanding conclusion. Want to win a Nobel prize and go down in history? Disprove evolution.

The bottom line

Science is one of the best tools humanity has ever developed to understand reality. The unfortunate truth is that we are easily fooled, and as Carl Sagan explained, “Science is a way to not fool ourselves.”

Science’s pretenders portray themselves as scientific but don’t adhere to the process that makes science so reliable. Yet there are no hard and fast lines that clearly distinguish between science and its pretenders. It’s a spectrum with lots of shades of gray.

Our desire to protect our beliefs can make us easy prey for science’s pretenders. No one can fool us like we can. The most difficult time to be skeptical is when we want, or don’t want, to believe. It all comes down to how willing we are to be honest with ourselves.

So ask yourself…what would change your mind? If you honestly can’t think of evidence that would cause you to reconsider your position, you’re not thinking like a scientist.

To learn more

Learn the characteristics of denial with the Cranky Uncle game

Merchants of Doubt: How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming

Special thanks to John Cook and Jonathan Stea for their feedback.

Posted by Guest Author on Wednesday, 18 August, 2021

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public.

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public.