Overconfident Idiots: Why Incompetence Breeds Certainty

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public. Please see this overview to find links to other reposts from Thinking is Power.

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public. Please see this overview to find links to other reposts from Thinking is Power.

The Dunning-Kruger effect explains why stupid people think they’re amazing.

On a sunny day in 1995, a man walked into a Pittsburgh bank. He smiled at the security cameras, pointed a gun at the cashiers, and demanded they give him money.

A few hours later, he robbed a second bank.

At 5 feet 6 inches tall and 270 pounds, the man wasn’t hard to miss. Especially since he wasn’t wearing a mask.

The evening news aired images of the man’s face to help the police identify the robber. They had his name within an hour, and immediately went to 45 year-old McArthur Wheeler’s home to arrest him.

Wheeler was dumbfounded. He couldn’t believe he had been caught. He didn’t even try to proclaim his innocence. Instead, he kept repeating, “But I wore the juice.”

During interrogation, Wheeler told the police he couldn’t understand how the security cameras had captured his image, because he had smeared lemon juice on his face to make himself invisible. The police assumed he was on drugs or alcohol. But nope. He was sober.

Just really, really wrong.

Apparently, Wheeler had learned that lemon juice could be used as an invisible ink, and concluded he could make himself invisible by rubbing it on his face. Of course, he wasn’t stupid, so he made sure to test his hypothesis. He put lemon juice on his face and took a selfie with a Polaroid camera. The blank photo proved his idea worked. Bam. He had discovered a fool-proof way to commit crimes and not be caught.

The day of the robbery, he put so much lemon juice on his face that it stung his eyes, making it hard for him to see. He marched into the bank, bare faced and smiling, confident that no one could see him.

Unskilled and unaware

Wheeler’s case caught the attention of psychology professor David Dunning and his graduate student, Justin Kruger, who wondered how the incompetent robber could have been so sure his plan would work.

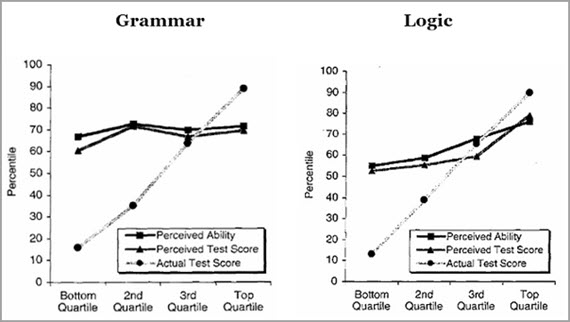

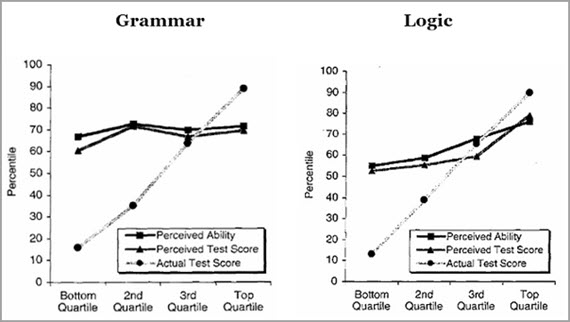

Dunning and Kruger set out to investigate using psychology’s favorite lab rat… undergraduate students. They asked the students to rate their abilities in logic and grammar relative to other students. Then they actually tested their abilities. The results were shocking. The students who performed the worst consistently and substantially overestimated how well they thought they did.

Figure 1: All students thought they were above average, but those in the bottom quartile overestimated their abilities the most, while those in the top quartile underestimated their abilities.

(Dunning and Kruger, 1999)

Interestingly, Dunning and Kruger also found the opposite for the top performers, who tended to underestimate their abilities. Their expertise allowed them to recognize their mistakes and see the gaps in their knowledge. Additionally, they assumed that, since something is easy for them, it must be just as easy for everyone else.

In a follow-up study at a shooting range, the pair tested gun hobbyists about safety, and found the same pattern. Those who scored the lowest greatly overestimated their knowledge, and those who scored the highest underestimated their knowledge.

The results have been replicated in an array of areas. One study found that 80% of drivers rated themselves as above average. Another found 94% of college professors also rated themselves as above average. (That’s not how averages work. We can’t all be above average!)

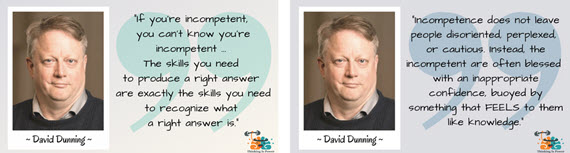

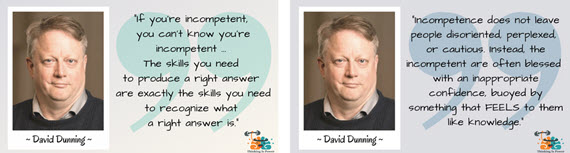

The result of their work is what is called the Dunning-Kruger effect, which is a cognitive bias in which those who are the least competent at a task overestimate their abilities. Apparently, the skills and knowledge required to be competent at a task are the same skills needed to evaluate one’s own competence. Or, as Dunning put it, if you’re incompetent, you can’t recognize how incompetent you are.

Basically, we are blind to our own ignorance. And, without real knowledge we are unable to recognize our mistakes and limits. We’re really confident, though, because an ignorant mind isn’t a blank slate. It’s cluttered with an illusion of knowledge, like misleading experiences, random facts, and intuitions.

We’re also unable to appreciate others’ expertise, and fail to incorporate feedback or improve. We’re already sure we know everything, so why would we listen to someone else?

Most of us have experienced the Dunning-Kruger effect in real life. It can be quite comical. (And irritating.) Your cranky uncle at Thanksgiving who thinks he knows everything. The cringe-inducing American Idol auditions by “singers” who cannot fathom why the judges are laughing. The commenters on any social media post LOUDLY proclaiming their point of view is fact and everyone else is stupid. The politician who confidently boasts that he knows more about everything than all of the experts.

But here’s the thing. We’re all confident idiots.

Think for a moment about something you’re really good at. It might be fixing cars, breeding Basset hounds, baking bread, playing Call of Duty…..anything you know a lot about. Now consider what the average person knows about your area of expertise. It’s probably not much, and some of it is probably wrong. They probably don’t even realize how much there is to know.

Now consider you’re as ignorant as that person in essentially every other area. If you didn’t just eat a slice of humble pie, I would suggest thinking a bit harder, because you’re probably dumber than you think you are.

As Dunning pointed out, “The first rule of the Dunning-Kruger club is you don’t know you’re a member of the Dunning-Kruger club.”

The Parable of the Graph

When my husband and I were first married, we spent a semester in Germany. In preparation, we bought books and CDs to learn to speak German. (This was before apps and smartphones.) Fortunately for us, we were in an area of the country where most people didn’t speak English. No problem. We knew how to speak German!

Or we thought we did. Most people were generous enough to humor us, but let’s just say there were incidents. On one occasion, while conducting a concert during a heat wave, my husband repeatedly told an audience that he was hot, and they were hot, too. Having forgotten to use the reflexive, he essentially told everyone how horny he was.

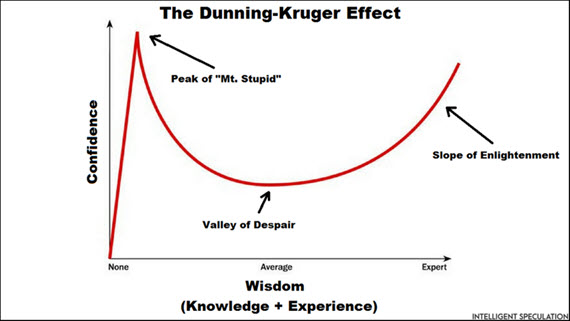

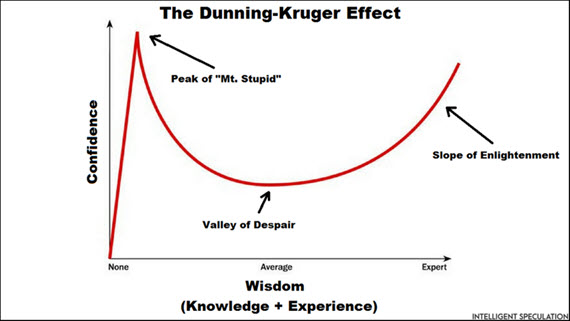

Having gained just enough knowledge to make us feel confident, we were on the Peak of Mt. Stupid. A little knowledge is a dangerous thing.

Figure 2: The Dunning-Kruger effect took off like wildfire on the internet, as it clearly touched a nerve. Memes and jokes went viral, as did this graph, which, while it seemed intuitive, was actually not part of the original research. However, in an ironic twist, Dunning later tested the graph and confirmed the internet was onto something!

Source: Intelligent Speculation

Actually, it’s crowded up there, full of people who watched a couple of YouTube videos and think they’ve discovered proof that NASA is hiding the fact that the Earth is flat, or the celebrity who spent a few hours on Google and concluded they know more about vaccines than scientists.

Getting off of Mt. Stupid isn’t automatic. Some stay up there for life. But hopefully, you learn enough to descend into the Valley of Despair. Confidence plummets because you realize there’s more to learn. It’s complicated. Oh, and there are people who know more than you!

If you persevere, you start to climb up the Slope of Enlightenment. You learn more, make connections, recognize nuance. You realize you may never actually really know for sure. You gain more mastery and your confidence increases.

And frustratingly, you see those at the top of Mt. Stupid and wonder how they can be so confident when they’re so clearly wrong.

How to Not Be a Confident Idiot

McArthur Wheeler was confident his plan was fool-proof, and convinced lemon juice would make him invisible. When the police showed him the surveillance videos, he thought they were fake. He just couldn’t believe he had been wrong. He kept repeating, “But I wore the juice!”

(Apparently Wheeler’s incompetence extended to photography, as when he turned the camera to take a selfie to test his plan, he had actually taken a photo of the ceiling!)

Wheeler’s confidence was because of his incompetence. He was too ignorant to recognize his mistakes, and made poor decisions because of it. In short, he had deceived himself.

So, if we don’t know what we don’t know, what’s the solution?

The Dunning-Kruger effect occurs because we are unable to objectively evaluate our knowledge and competence. Therefore, the solution boils down to metacognition, or being aware of our thought processes, so that we can more accurately and honestly evaluate our own knowledge and skills.

Also key is intellectual humility, or recognizing that we might be wrong.

So, ask yourself how you know something. And maybe more importantly, how would you know if you were wrong. Honestly evaluate the evidence. Consider that you might not even know enough to be capable of evaluating the evidence.

Be curious about what you don’t know. Actively look for your blindspots. Ask for feedback from experts, and be open to incorporating their suggestions. If they tell you you’ve made a mistake or overlooked something, don’t get defensive. Listen and learn.

Get comfortable with uncertainty. Most issues are more complicated than we think, and understanding the complexity and nuance requires deep knowledge and expertise.

Oh, and monitor your confidence. Don’t wear the juice!

The Take-Home Message

Many of us go through the world confident in what we think we know. Unfortunately, our hubris stops us from actually achieving real knowledge. Being able to accurately assess what we know and how we are thinking is essential to true understanding. Often, our confidence is an illusion, based on an illusion of knowledge. We’re dumb and proud……completely unaware of how much we don’t know.

Making better decisions requires better thinking. We are experts at fooling ourselves, and we love to be right and know everything. But, if our goal is real knowledge, we need to recognize the limits of our knowledge.

One more thing

The Dunning-Kruger effect is a new name for a condition that scientists and philosophers have been pondering for centuries. They’ve said it better than I ever could, so I will let them have the last word.

Posted by Guest Author on Wednesday, 13 October, 2021

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public. Please see this overview to find links to other reposts from Thinking is Power.

This is a re-post from the Thinking is Power website maintained by Melanie Trecek-King where she regularly writes about many aspects of critical thinking in an effort to provide accessible and engaging critical thinking information to the general public. Please see this overview to find links to other reposts from Thinking is Power.