The city government of Manchester, England is coming under some fire for choosing to lease space on pavements (also known as sidewalks) for electronic display advertisements, or "digital out of home advertising." Criticism is twofold in nature. Some point out that crowding of pavements with bulky fixed installations is an insult to pedestrians. Others are looking at the problem a different way, at how this choice boosts energy consumption.

How much energy? Quite a bit.

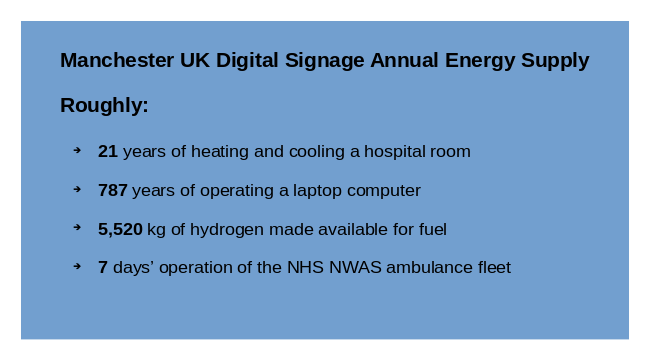

"According to analysis of data revealed by a freedom of information request, each of the 86 digital advertising boards in Manchester city centre uses 11,501kWh of electricity every year."

Manchester electronic ad boards each use electricity of three households

It seems an awfully large number, perhaps even wrong. But it works out to about 1.3kW to power each sign. Not difficult to achieve if nobody is thinking about efficiency at any point in the design and decision process leading to signs planted on pavements.

Manchester's city council declared a "climate emergency" in 2019. In the face of that, energy profligacy to the tune of 11.5kWh to run a single sign for a year should be more than conspicuous but even unthinkable. If we think of "climate emergency" as something akin to "war emergency," take this matter seriously and are not only paying lip service, very hungry twinkling signage is indeed a puzzling choice to make. How do Manchester's leaders feel they're guiding their constituents to victory with choices to burn more energy for no particularly compelling reason?

And by extension and not to unfairly pick on Manchester, if by "we" we mean voting constituencies in general, many of us are tolerating this type of undermining behavior in the face of disaster.

But we need to see what poor decisions look like, understand how and why thoughtless behavior can add up to large numbers, and how being oblivious has ripple effects. Knowing those things, we can identify options for tuning, ways of coming to at least a partial solution to something that unfortunately— due to matters unrelated to climate— does have something of the nature of a dilemma to it.

Tradeoffs are required, but happily there's likely room for productive trading.

Facing criticism over energy waste, Manchester's city government immediately deployed the "no worries it's renewable power" card. At 11.5 MWh/year of electrical consumption to power each sign, the situation affords a nice opportunity to interrogate "it's ok, it's powered by renewables," an easy excuse to make but one that can support only a limited number of confused or deeply motivated thinkers leaning upon it.

In particular, do choices like this make even more difficult our substitution problem? Replacing our legacy energy supplies is a problem that continues to emerge and come into better focus as we come to grips with the scale and deep reach of our fossil fuel addiction. What's the effect of thoughtless actions on that?

It helps to not think of abstracts like "kWh," or to translate such quantities into more familiar terms. For instance, at the now typical 4 miles per kWh for an EV, over a year each of these signs in Manchester is dissipating enough energy to propel a vehicle for over 45,000 miles, or 6 years' usage of the average private vehicle in the UK. Collectively, between the signs in question over one million miles or 144 years of usage.

According to this document prepared for the UK parliament, EV consumption in the UK by 2050 will reach the neigborhood of 100TWh.* The total UK electrical energy supply in 2020 was ~330TWh. Making 330TWh into 440TWh is a nontrivial job, particularly when it arrives in parallel with a lot of other challenges.

How can we make our substitution job easier? Pehaps by making smarter choices. If we know that the energy-consuming things we already operate and often actually need are a big challenge to transition to modernized, permanent energy supplies, is it a good idea to add more equipment needing energy supply modernization? If we're all aware that the value of that new equipment as a practical matter is very dubious, is adding this freight to our already-too-large burden an intelligent decision?

The answer lies a little bit in "what's the impact of the more useless things we're adding?" Manchester's vibrant electronic touts are of course just tiny drop in the relative bucket, consumption-wise. How's that looking in the big picture? What's the impact of many Manchesters? What if we all unite with Manchester?

According to market research outfit Route, electronic ad screens multiplied in the UK from 7,285 to 11,024 in the single year 2018-2019. We don't know how Manchester's screens fall compared to consumption of other screens, but thinking like-for-like as though everybody were making the same bad choice, that would be total electrical consumption of these devices growing from about ~80.5GWh to ~126.5GWh in a single year.

So, we can see what happens when everybody unites and (ironically) act together as though they're alone on the planet, in large numbers.

What are we trading for this signage, in terms of available "green renewable power?" By now consumption will be even worse but let's stick with 2018's ending electronic signage consumption figure for the UK. 126.5GWh will propel a typical EV for over 500 million miles or, thinking of it another way, provide 72,000 years of personal transport. What's more useful: encouragement to buy more things, or transport?

Given that we don't actually have all the renewable power in hand that we need to complete a transition right now or even quite a long time from now, is it really a good idea to continue behaving as though there was no "climate emergency," to continue fostering and even growing habits we know are not supported by the energy income they need?

As goes Manchester, so go the rest of us. There's nothing specially bad about Manchester. If Manchester doesn't make sensible choices, there's no reason to believe anybody else will, and few are in a position to judge Manchester. We're united with Manchester, win or lose. So let's do better together.

Stepping back from the immediate causes of complaint in this matter— pavement blockage, and energy waste making a hard job even more difficult— "just say no" means saying "something benefiting the public to the tune of £2.4m per year must be lost." Manchester's city council is desperately in need of money for many reasons and purposes, an uncontroversial fact. Manchester can't afford to "just say no" without having to trade something away. Manchester's problem is widely shared.

How to address this? How to get to "yes, this can work?" The matter of pavement sharing is complicated and we can't address it here. But digital signage energy consumption is likely a lot more tunable, amenable to improvement. Helping to achieve a balance between "we need income" and "not at any cost" is arguably a matter that can be handled when setting terms in lease agreements, and those need not be draconian or confrontational.

Assuming that energy consumption figures for these devices are accurate, they're an engineering failure if by "engineering success" we mean that engineers have scrupulously accounted for all "trades," that all factors affecting the design have been systematically weighed and taken into account in a final implementation. In this trade process and not least, does sign engineering take into account external costs, as all engineering on a planet supporting 7.75 billion persons absolutely must? Here, obvously not.

As it turns out, these devices reek of inefficiency, of suboptimal engineering that probably has suffered not from poor engineering talent but rather "get it out the door as fast as possible."

For instance, in climates too warm or too cool, much outdoor digital signage currently requires active cooling or heating, heaping on more wasted energy consumption. Given the natural shape of this equipment and options for internal hardware, it's not a huge design lift to prepare a device for hot and cold by exploiting the "stack effect" and combining that with simple shutters controlled by bimetallics to afford thermal control without adding kWh to the plan. That kind of refinement is mostly a matter of paying attention, or being encouraged to pay attention. This kind of scrupulous attention can be inculcated and made habitual, by nudges.

What can city councils do in the absence of responsive regulatory pressure or enthusiastic self-improvement on the part of the advertising industry? Start by collaborating with advertising customers to make these systems more efficient. Ultimately this is a situation where coercion is possible, even while positive, friendly collaboration is of course the best starting point. Here are a few items from the menu of options.

Posted by Doug Bostrom on Tuesday, 18 January, 2022

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |