This is a repost from Justin Hendrix on Tech Policy Press published on January 14, 2022. It provides a neat summary of the recently published paper "The psychological drivers of misinformation belief and its resistance to correction" (Ecker et al. 2022).

From COVID-19 and vaccine conspiracies to false claims around elections, misinformation is a persistent and arguably growing problem in most democracies. In Nature, a team of nine researchers from the fields of psychology, mass media & communication have published a review of available research on the factors that lead people to “form or endorse misinformed views, and the psychological barriers” to changing their minds.

Acknowledging that “the internet is an ideal medium for the fast spread of falsehoods at the expense of accurate information,” the authors point out that technology is not the only culprit, and a variety of interventions that have sought to solve misinformation by addressing the “misunderstanding of, or lack of access to, facts” have been less than effective. The so-called “information deficit model,” they argue, ignores “cognitive, social and affective drivers of attitude formation and truth judgements.”

The authors are particularly concerned with the problem of misinformation as it concerns scientific information, such as on climate change or public health matters. In order to better understand what can be done to address the problem, they look at the “theoretical models that have been proposed to explain misinformation’s resistance to correction” and extract guidance for those who would seek to intervene. Then, the authors return to “the broader societal trends that have contributed to the rise of misinformation” and what might be done in the fields of journalism, education and policy to address the problem.

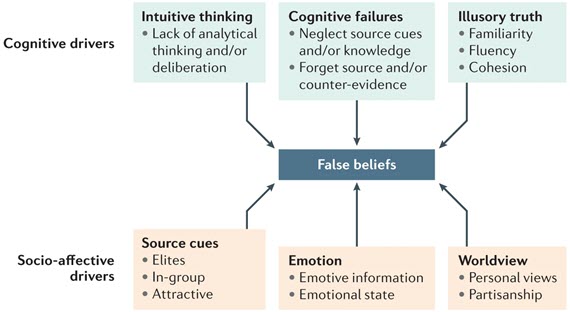

The authors summarize what is known about a variety of drivers of false beliefs, noting that they “generally arise through the same mechanisms that establish accurate beliefs” and the human weakness for trusting the “gut”. For a variety of reasons, people develop shortcuts when processing information, often defaulting to conclusions rather than evaluating new information critically. A complex set of variables related to information sources, emotional factors and a variety of other cues can lead to the formation of false beliefs. And, people often share information with little focus on its veracity, but rather to accomplish other goals- from self-promotion to signaling group membership to simply sating a desire to ‘watch the world burn’.

Figure 1: Some of the main cognitive (green) and socio-affective (orange) factors that can facilitate the formation of false beliefs when individuals are exposed to misinformation. Not all factors will always be relevant, but multiple factors often contribute to false beliefs. Source: Nature Reviews: Psychology, Volume 1, January 2022

Barriers to belief revision are also complex, since “the original information is not simply erased or replaced” once corrective information is introduced. There is evidence that misinformation can be “reactivated and retrieved” even after an individual receives accurate information that contradicts it. A variety of factors affect whether correct information can win out. One theory looks at how information is integrated in a person’s “memory network”. Another complementary theory looks at “selective retrieval” and is backed up by neuro-imaging evidence.

Other research looks at “the influence of social and affective mechanisms” at play. These range from an individuals assessment of “source credibility” to their worldview– the “values and belief system that grounds their personal and sociocultural identity.” Messages that threaten a person’s identity are more likely to be rejected. Emotion plays a major role- from the degree of arousal or discomfort information might generate to the extent to which it might cause an “emotional recalibration” to account for it.

The authors identify three general types of corrections. They include fact-based corrections that address “inaccuracies in the misinformation and provides accurate information,” those that identify logical fallacies in the misinformation, and those that “undermine the plausibility of the misinformation or credibility of its source.” These corrections can be applied before the introduction of misinformation (pre-bunking) or after (de-bunking), and best practices for both approaches have begun to emerge, including methods to inoculate individuals to misinformation before they are exposed to it and how to pair corrections with social norms. These best practices are generally applicable in a social media environment, but there are some nuances, particularly on platforms where interventions may be observed by others and could be “experienced as embarrassing or confrontational.”

Figure 2: Different strategies for countering misinformation are available to practitioners at different time points. If no misinformation is circulating but there is potential for it to emerge in the future, practitioners can consider possible misinformation sources and anticipate misinformation themes. Based on this assessment, practitioners can prepare fact-based alternative accounts, and either continue monitoring the situation while preparing for a quick response, or deploy pre-emptive (prebunking) or reactive (debunking) interventions, depending on the traction of the misinformation. Prebunking can take various forms, from simple warnings to more involved literacy interventions. Debunking can start either with a pithy counterfact that recipients ought to remember or with dismissal of the core ‘myth’. Debunking should provide a plausible alternative cause for an event or factual details, preface the misinformation with a warning and explain any logical fallacies or persuasive techniques used to promote the misinformation. Debunking should end with a factual statement. Source: Nature Reviews: Psychology, Volume 1, January 2022

The emerging science of misinformation points to a number of important implications, including for practitioners such as journalists as well as for information consumers. But the authors see the limitations of both groups, which is where policymakers come in. “Ultimately, even if practitioners and information consumers apply all of these strategies to reduce the impact of misinformation, their efforts will be stymied if media platforms continue to amplify misinformation,” they say, pointing to both YouTube and Fox News as examples of companies that appear economically incentivized to spread misinformation.

The job of policymakers, in this context, is to consider “penalties for creating and disseminating disinformation where intentionality and harm can be established, and mandating platforms to be more proactive, transparent and effective in their dealings with misinformation.” Acknowledging that concerns over free speech must be weighed and balanced against the potential harms of misinformation, other policy recommendations include:

Notably, the authors suggest broader interventions to strengthen trust may yield results in the fight against misinformation, such as “reducing the social inequality that breeds distrust in experts and contributes to vulnerability and misinformation.”

Having reviewed the literature, the authors also offer their recommendations for future research, including larger studies, better methods, longer term studies, more focus on media modalities other than text, and more translational research to explore “the causal impacts of misinformation and corrections on beliefs and behaviors.” Ultimately, what is needed is more work across disciplines, particularly at the “intersection of psychology, political science and social network analysis, and the development of a more sophisticated psychology of misinformation.”

About the author:

Justin Hendrix is CEO and Editor of Tech Policy Press, a new nonprofit media venture concerned with the intersection of technology and democracy. Previously, he was Executive Director of NYC Media Lab. He spent over a decade at The Economist in roles including Vice President, Business Development & Innovation. He is an associate research scientist and adjunct professor at NYU Tandon School of Engineering. Opinions expressed here are his own. Follow Justin on Twitter.

Posted by Guest Author on Wednesday, 26 January, 2022

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |