This is a blog post version of John Cook's paper "Cranky Uncle: a game building resilience against climate misinformation" published in the Austrian periodical Plus Lucis for educators in 2021. We are re-posting it here with their permission to make translated versions readily available.

Misinformation about climate change does damage in multiple ways. It causes people to believe wrong things [1], polarizes the public [2], and reduces trust in scientists [3]. Climate misinformation reduces support for climate action [1], delaying policies to mitigate climate change [4]. One of the most insidious aspects of misinformation is it can cancel out accurate information [5, 6]. When people are presented with fact and myth but don’t know how to resolve the conflict between the two, the risk is they disengage and believe neither.

Consequently, an effective way to counter misinformation is to help people resolve the conflict between facts and myths. This is achieved by inoculating the public against the misleading rhetorical techniques used in misinformation. Inoculation theory is a branch of psychological research that applies the concept of vaccination to knowledge [7]. Just as exposing people to a weakened form of a virus develops resistance to the real virus, similarly, exposing people to a weakened form of misinformation builds immunity to real-world misinformation. Inoculation has been found to be effective in neutralizing misinformation casting doubt on the scientific consensus on human-caused global warming [2, 6]. Inoculation messages are also long lasting [8]

There are two main inoculation approaches – fact-based and logic-based [9]. Fact-based inoculations expose how the misinformation is wrong by explaining the facts. Logic-based inoculations explain the rhetorical techniques or logical fallacies used by the myth to distort the facts. While both methods are effective in neutralizing misinformation [10, 11], the logic-based approach is particularly attractive because it works across topics. In one experiment, when participants were inoculated against a rhetorical technique used by the tobacco industry, they were no longer misled by the same technique used in climate misinformation [2]. Logic-based inoculation is like a universal vaccine against misinformation.

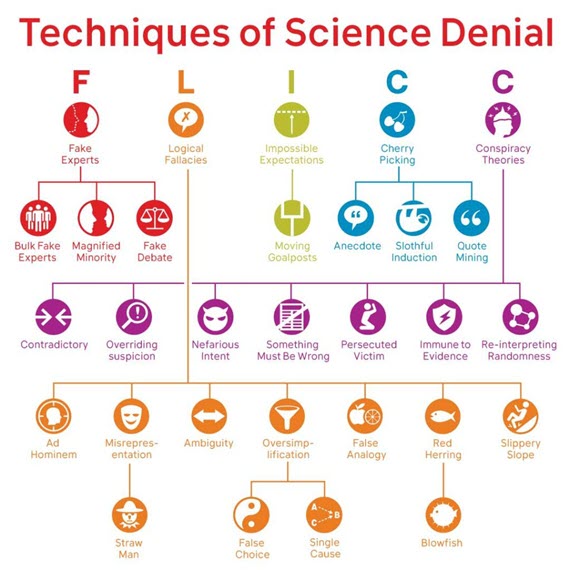

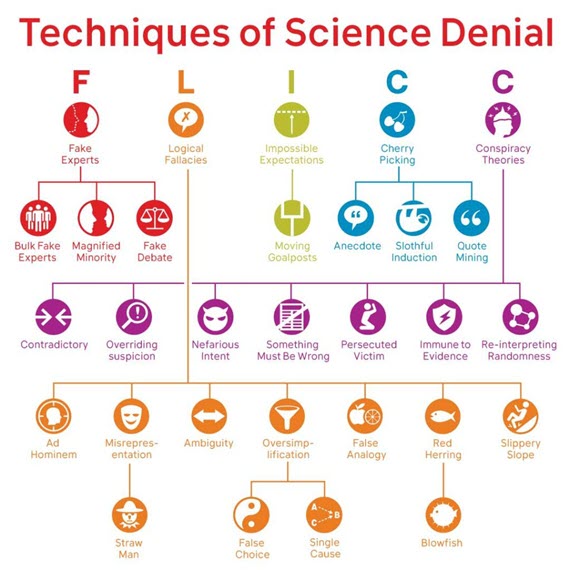

Figure 1. The FLICC taxonomy, organising the five categories of science denial techniques.

Identifying the techniques of denial requires a framework that organises and describes the misleading fallacies found in misinformation. A useful framework is the five techniques of science denial: fake experts, logical fallacies, impossible expectations, cherry picking, and conspiracy theories [12]. This framework, summarized with the acronym FLICC, has been subsequently expanded over the years into a more detailed taxonomy of rhetorical techniques, logical fallacies, and conspiratorial traits (see Figure 1, adapted from [13]).

Parallel argumentation is a powerful technique for explaining the misleading techniques of misinformation. This involves transplanting the flawed logic from a fallacious argument into an analogous situation, often an extreme or absurd one [14]. This approach has strong pedagogical value, expressing abstract logical concepts in concrete, relatable terms [15]. By focusing on reasoning errors, parallel argumentation debunks misinformation while sidestepping the need to provide complicated explanations. It is also a technique conducive to entertaining and humorous applications. Figure 2 shows some examples of parallel arguments in cartoon form, adapted from the book Cranky Uncle vs. Climate Change [16].

| Figure 2. Two examples of parallel argumentation in cartoon form. (a) The argument “cold weather disproves global warming” and a parallel argument illustrating the anecdote fallacy. (b) The argument “climate has changed naturally in the past so what’s happening now must be natural” and a parallel argument illustrating the single cause fallacy. Click for larger images! | |

Generally, humor in science communication offers a number of benefits. Cartoons about climate change provoke mirth, which mediates greater support for climate action [17]. Humorous messages are more engaging, showing the greatest impact with people who are disengaged from issues like climate change [18]. Using humor to explain a serious topic such as climate change with humor makes the issue less threatening and more accessible [19]. People respond to humorous messages with less counterarguing [20].

However, humor can be a double-edged sword as some benefits come with potential drawbacks. While humor makes climate change less intimidating, people also come away less concerned about the issue relative to a serious climate message [21]. Similarly, humorous messages may lead to less counterarguing but they’re also perceived as less informative than serious messages, even when containing the same information [22].

Cartoon parallel arguments have been shown to be effective in debunking misinformation about vaccines [23] and climate change [24]. Using mediation analysis with eye-tracking data, humorous cartoons were found to be successful in discrediting misinformation because people spent more time paying attention to the cartoons [24]. This research shows that using cartoon parallel arguments are an effective way to deliver explanations of logical fallacies and inoculate people against misinformation.

One limitation of logic-based inoculation is that it depends on building resilience by increasing critical thinking, a cognitively effortful activity. The vast majority of our thinking is effortless, fast thinking (e.g., mental shortcuts or heuristics) rather than effortful, slow thinking (e.g., critically assessing the logical validity of misinformation), an aspect of psychology explored in the book Fast and Slow Thinking [25]. This reliance on heuristics makes people vulnerable to logical fallacies which can be superficially persuasive. However, Kahnemann also discusses a third type of thinking—expert heuristics. When a person practises a task a sufficient number of times, the slow thinking processes required to complete the difficult task evolve into fast thinking responses.

Games offer engaging tools for incentivizing people to repeatedly perform misinformation-spotting tasks in order to build up their critical thinking skills. Games that are fun to engage with while serving a useful educational purpose are known as serious games [26]. Gameplay elements such as achievement rewards offer learning incentives [27], while leaderboards and player-to-player features add social and community elements [28]. In the case of misinformation, sequences of quizzes where players repeatedly identify fallacies in misleading arguments offer the potential to convert the slow thinking process of analyzing the logic of an argument into easier, faster heuristics.

Games are already being explored as a tool for building resilience against misinformation, using an approach known as active inoculation [29]. Typically, inoculation interventions are passive, with messages received in a one-way direction from communicator to audience. In contrast, active inoculation involves participants in an interactive inoculation process - having them learn the techniques of science denial by ironically learning to use the misleading techniques themselves. Digital games have already been applied in games targeting fake news [30] and misinformation undermining democracy [31].

The Cranky Uncle game adopts an active inoculation approach, where a Cranky Uncle cartoon character mentors players to learn the techniques of science denial. Cranky Uncle is a free game available on iPhone (sks.to/crankyiphone) and Android (sks.to/crankyandroid) smartphones as well as web browsers (app.crankyuncle.info). The player’s aim is to become a “cranky uncle”—a science denier who skillfully applies a variety of logically flawed argumentation techniques to reject the conclusions of the scientific community. By adopting the mindset of a cranky uncle, the player develops a deeper understanding of science denial techniques, thus acquiring the knowledge to resist misleading persuasion attempts in the future.

Figure 3: Sample of “trail” screens, explaining techniques of science denial. (a) Denial techniques. (b) Explanation of “Overriding suspicion”. (c) Explanation of “Overriding suspicion ctd. (d) Final screen of “Overriding suspicion” trail.

One danger of serious games is players can lose motivation if they see the game as all education and no fun. By featuring an ornery cartoon character as a mentor and humorous examples of logical fallacies (e.g., parallel arguments in cartoon form), this pitfall is avoided. Humor is employed throughout the trails, with Cranky Uncle’s prickly personality shining through. Fun is one of the key predictors of players’ willingness to play a game again [32]. In the Cranky Uncle game, humor is an integral part of the learning process, with cartoon analogies providing not only humor but also instructive illustrations of fallacious logic

Explanations of denial techniques form the spine of the game (Figure 3a). Each denial technique is explained in a “trail”, a sequence of screens featuring text explanations (Figure 3b, 3c) and cartoon examples of logical fallacies. Gameplay elements such as point accumulation (Figure 3d) and leveling up (Figure 4d) provide regular feedback, incentivizing the player to continue deeper into the game and develop greater resilience against misinformation.

After completing trails, players practise their newly acquired critical thinking knowledge by completing quiz questions. The game features three types of questions. The first type are true/false questions (Figure 4a)—either false statements containing a logical fallacy or inherently true statements (e.g., tautologies such as “people are dying who never died before”). The second question type asks the player to identify a specific fallacy from several false statements (Figure 4b). The third question type presents a false statement (in text or cartoon form) with the player identifying the denial technique from four options (Figure 4c).

Games show the greatest player outcomes when they combine a variety of achievement notifications [27]. The Cranky Uncle game provides achievement notifications in a number of ways. Players are regularly shown their points progress throughout the game (Figures 3d) and given immediate feedback in response to correct or incorrect quiz answers. When a player levels up, they are shown a pop-up informing them of their new cranky mood (e.g., “peevish”, Figure 4d).

Figure 4: Examples of quiz questions and achievement notification. (a) True/false. (b) Fallacy examples. (c) Multiple fallacies. (d) Notification when a player levels up.

While the Cranky Uncle game can be played by any member of the public with a smartphone or access to a web browser, arguably its greatest social impact will be as a classroom activity. Critical thinking and resilience against misinformation are skills required across many grade levels and subjects. Currently, educators are using the game in classes from middle school to grad school at university level, across subjects as diverse as biology, environmental science, English, and philosophy. To provide additional educational scaffolding, a Teachers’ Guide to Cranky Uncle was published, offering a number of critical thinking activities to complement and reinforce the game’s content [33],

In recent years, misinformation has been an ever-present problem, affecting all aspects of society. Amplified by social media platforms and exacerbated by global developments such as the COVID-19 pandemic, the problem is complex, ubiquitous, and interconnected. Holistic solutions are required that can be scaled up to address the immensity of the challenge—interdisciplinary projects combining science, technology, and the arts. Art enables communicators to package scientific information in entertaining formats that engage the attention of disengaged audiences. Technology enables the dissemination of interactive games at a scale commensurate with the problem. Science provides evidence-based approaches for addressing misinformation such as research into logic-based inoculation and cartoon parallel arguments. The Cranky Uncle game brings together these diverse threads, synthesizing research into inoculation, critical thinking, and science humor, wrapped in a technological package that makes critical thinking content accessible to players in an engaging, interactive format.

References

[1] Ranney & Clark (2016). Climate Change Conceptual Change: Scientific Information Can Transform Attitudes. Topics in Cognitive Science, 8(1), 49-75.

[2] Cook et al. (2017). Neutralizing misinformation through inoculation: Exposing misleading argumentation techniques reduces their influence. PLOS ONE, 12, e0175799.

[3] Biddle & Leuschner (2015). Climate skepticism and the manufacture of doubt: can dissent in science be epistemically detrimental? European Journal for Philosophy of Science, 5(3), 261-278.

[4] Lewandowsky (2020). Climate change, disinformation, and how to combat it. Annual Review of Public Health, 42.

[5] McCright et al. (2016). Examining the effectiveness of climate change frames in the face of a climate change denial counter-frame. Topics in Cognitive Science, 8(1), 76-97.

[6] van der Linden et al. (2017). Inoculating the public against misinformation about climate change. Global Challenges, 1, 1600008.

[7] Compton et al. (2016). Persuading others to avoid persuasion: Inoculation theory and resistant health attitudes. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 122.

[8] Maertens et al. (2020). Combatting climate change misinformation: Evidence for longevity of inoculation and consensus messaging effects. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 70, 101455.

[9] Banas & Miller (2013). Inducing resistance to conspiracy theory propaganda: Testing inoculation and metainoculation strategies. Human Communication Research, 39(2), 184-207.

[10] Vraga et al. (2020). Testing the effectiveness of correction placement and type on Instagram. The International Journal of Press/Politics, 25(4), 632-652.

[11] Schmid & Betsch (2019). Effective strategies for rebutting science denialism in public discussions. Nature Human Behaviour, 3, 931-939.

[12] Hoofnagle, M. (2007, April 30). Hello Scienceblogs. Denialism Blog. Retrieved from http://scienceblogs.com/denialism/about/

[13] Cook (2021). Deconstructing Climate Science Denial. In Holmes, D. & Richardson, L. M. (Eds.) Edward Elgar Research Handbook in Communicating Climate Change. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

[14] Cook et al. (2018). Deconstructing climate misinformation to identify reasoning errors. Environmental Research Letters, 13, 024018.

[15] Juthe (2008). Refutation by parallel argument. Argumentation, 23(2), 133-169.

[16] Cook, J. (2020). Cranky Uncle vs. Climate Change: How to Understand and Respond to Climate Science Deniers. New York, NY: Citadel Press.

[17] McKasy, M., Cacciatore, M. A., Yeo, S. K., Zhang, J. S., Cook, J., & Olaleye, R. M. (2021, August). The Impact of Emotion and Humor on Support for Global Warming Action. Annual Conference of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (AEJMC), New Orleans, LA (virtual).

[18] Brewer & McKnight (2015). Climate as comedy: The effects of satirical television news on climate change perceptions. Science Communication, 37(5), 635-657.

[19] Boykoff & Osnes (2019). A laughing matter? Confronting climate change through humor. Political Geography, 68, 154-163.

[20] Nabi et al. (2007). All joking aside: A serious investigation into the persuasive effect of funny social issue messages. Communication Monographs, 74(1), 29-54.

[21] Bore & Reid (2014). Laughing in the face of climate change? Satire as a device for engaging audiences in public debate. Science Communication, 36(4), 454-478.

[22] Skurka et al. (2018). Pathways of influence in emotional appeals: Benefits and tradeoffs of using fear or humor to promote climate change-related intentions and risk perceptions. Journal of Communication, 68(1), 169-193.

[23] Kim et al. (2020a). An Eye Tracking Approach to Understanding Misinformation and Correction Strategies on Social Media: The Mediating Role of Attention and Credibility to Reduce HPV Vaccine Misperceptions. Health Communication, 1-10.

[24] Vraga et al. (2019). Testing logic-based and humor-based corrections for science, health, and political misinformation on social media. Journal of Broadcasting and Electronic Media, 63, 393-414.

[25] Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

[26] Girard et al. (2012). Serious games as new educational tools: How effective are they? A meta-analysis of recent studies. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 29, 207-219.

[27] Blair et al. (2016). Understanding the role of achievements in game-based learning. International Journal of Serious Games, 3(4), 47-56.

[28] Paavilainen et al. (2017). A review of social features in social network games. Transactions of the Digital Games Research Association, 3(2).

[29] Roozenbeek & van der Linden (2018). The fake news game: actively inoculating against the risk of misinformation. Journal of Risk Research, 1-11.

[30] Roozenbeek & van der Linden (2019). Fake news game confers psychological resistance against online misinformation. Palgrave Communications, 5(1), 12.

[31] Roozenbeek & van der Linden (2020). Breaking Harmony Square: A game that “inoculates” against political misinformation. The Harvard Kennedy School Misinformation Review

[32] Imbellone et al. (2015). Serious Games for Mobile Devices: the InTouch Project Case Study. International Journal of Serious Games, 2(1).

[33] Cook, J. (2021b, January 27). The Teachers’ Guide to Cranky Uncle. CrankyUncle.com

Related Publications

Published in 2022: The cranky uncle game—combining humor and gamification to build student resilience against climate misinformation (PDF)

Posted by John Cook on Wednesday, 24 August, 2022

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |