On February 14, 2023 we announced our Rebuttal Update Project. This included an ask for feedback about the added "At a glance" section in the updated basic rebuttal versions. This weekly blog post series highlights this new section of one of the updated basic rebuttal versions and serves as a "bump" for our ask. This week features "Is Greenland gaining or losing ice". More will follow in the upcoming weeks. Please follow the Further Reading link at the bottom to read the full rebuttal and to join the discussion in the comment thread there.

The interior of Greenland features a huge ice sheet that covers some 80% of that large island. Up to three kilometres thick, the sheet contains a whopping 2.9 million cubic kilometres of ice. If that all melted, global sea level would go up by around seven and a half metres. So it would obviously be good if that didn't happen.

Read any science about ice-sheets and you will soon run into a term that will become familiar: 'mass balance'. Mass balance is an expression of the health of any ice-sheet. Ice-sheets gain mass by snowfall and lose mass by 'ablation', a term covering sublimation, evaporation melt, and meltwater runoff, plus solid ice discharge by the glaciers that drain them. If the value for mass balance of an ice sheet is a positive number, the sheet is growing. But a negative value means the sheet is dwindling.

Since 1991, satellites have obtained continuous data on the Greenland ice-sheet, using radar, lasers and sensitive instruments that can detect changes in local gravity. Such methods allow mass balance to be calculated.

With over 30 years of satellite data now at our disposal, we can step back and look at the big picture. The Greenland ice sheet was close to a neutral state of balance in the 1990s. Since then however, annual losses have risen. One recent paper calculates that Greenland lost almost 4,000 billion tonnes of ice between 1992 and 2018, adding almost eleven millimetres to global sea levels.

Reduction of ice mass balance has occurred for two key reasons. Firstly there is increased meltwater run-off. Have you seen imagery of bright blue pools connected to rivers, flowing across the surface of the ice-sheet, to disappear down into it in spectacular cascades? That's the run-off. Secondly, there is glacier instability - whereby glaciers speed up in their discharge of ice, ultimately to the ocean, with those videos of spectacular calving events many of you will have seen. In Greenland, it's thought that these two processes account for about half of ice-sheet loss each.

Of course, the rate of ice loss varies from year to year. It depends on weather patterns. A cooler year with a lot of snowfall will provide a considerable counter-weight to the loss processes. Then again, in June 2023 the temperature rose to 0.4oC at the Summit Station, a research facility situated 3,216 metres above sea level and near the high-point of the ice-sheet. That has only happened five times in the 34 years since the station was established. Like anywhere else, the year to year pattern is pretty varied: however it's the multidecadal trend that matters and that is very definitely downwards.

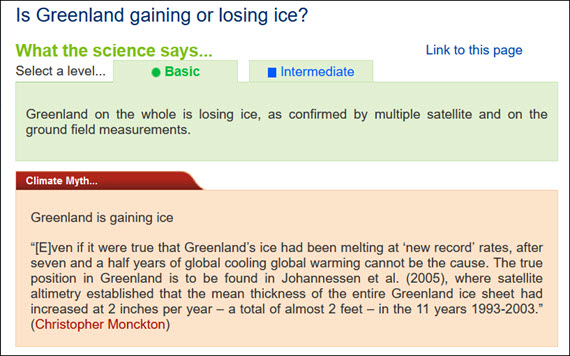

It never pays to pick short time-spans when discussing matters of long-term climate trends. Statements like the one by Christopher Monckton in the myth-box above, made in 2009, have simply been made invalid by the march of time.

Please use this form to provide feedback about this new "At a glance" section. Read a more technical version below or dig deeper via the tabs above!

In case you'd like to explore more of our recently updated rebuttals, here are the links to all of them:

If you think that projects like these rebuttal updates are a good idea, please visit our support page to contribute!

Posted by John Mason on Tuesday, 27 February, 2024

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |