This is a re-post from The Climate Brink by Andrew Dessler

In the wake of any unusual weather event, someone inevitably asks, “Did climate change cause this?” In the most literal sense, that answer is almost always no. Climate change is never the sole cause of hurricanes, heat waves, droughts, or any other disaster, because weather variability always plays a primary role in the genesis of the events.

However, climate change can make these events more intense and, given the non-linearities in the damages, this can vastly increase the damage and misery from extreme weather. So quantifying the role of climate change is therefore of great interest.

To do this, scientists turn to extreme event attribution studies. These rely on three separate lines of evidence. The first is the observational record: If you have good observations of the climate over a long enough period, the data set can be statistically analyzed to determine whether the event in question is becoming more frequent as the climate warms.

But correlation does not prove causality, so you need the second line of evidence: a physical understanding of why a particular extreme is getting worse as the climate warms. It should be obvious to readers of this substack why, in a warmer world, we expect to get more frequent heat waves. This physical understanding adds to our con?dence that climate change is a factor in the occurrence of heat waves.

Finally, we look to computer simulations of the climate. The most common approach is to produce two different simulations of the climate: One simulation is of the real world, so it includes increasing greenhouse gases and a warming climate. The other simulation is what’s known as a counterfactual world — an imaginary world in which humans are not adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, so the climate is not warming. We compare the simulations to see if the extreme we’re investigating occurs more frequently in the warmer world.

If we have all three lines of evidence, we can be confident that the event in question is connected to climate change. Essentially all heat waves fall into this category. On the other hand, we have zero lines of evidence for tornado outbreaks, so we don’t really have anything to say about how climate change is affecting those.

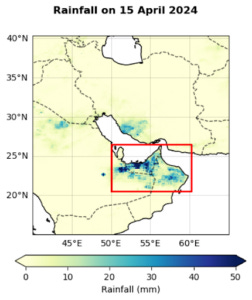

Given this, was the rainfall in Dubai in mid-April turbocharged by climate change? Luckily, the World Weather Attribution project has already weighed in. When we look for the three pillars, we find:

There is indeed a trend in intense precipitation in the region.

We have a physical understanding of why extreme precipitation gets more intense as the climate warms.

However, the climate models currently do not reproduce the observed trend in intense precipitation.

So we have two of three planks for confident attribution — and we all know that two out of three ain’t bad1. But it’s also not as strong as we’d like, so I conclude that we have weak-to-moderate confidence that global warming contributed to the Dubai flooding.

Attributions that come out a few days after the event are necessarily preliminary and I expect more analyses will show up in the peer-reviewed literature in the next year or two. Such analysis may increase our confidence in a climate connection, or it may not. One thing we can be confident about, though, is that it wasn’t cloud seeding.

Regardless of the outcome of this event’s attribution, rest assured that climate change is making all sorts of extreme weather events more severe.

Posted by Guest Author on Monday, 29 April, 2024

|

The Skeptical Science website by Skeptical Science is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License. |