Arguments

Arguments

Software

Software

Resources

Comments

Resources

Comments

The Consensus Project

The Consensus Project

Translations

Translations

About

Support

About

Support

Latest Posts

- Sabin 33 #25 - Are wind projects hurting farmers and rural communities?

- A worse-than-current-policy world?

- 2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #16

- Fact brief - Is climate change a net benefit for society?

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #16 2025

- Climate Adam: Climate Scientist Reacts to Elon Musk

- Sabin 33 #24 - Is wind power too expensive?

- EGU2025 - Picking and chosing sessions to attend on site in Vienna

- 2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #15

- Fact brief - Is the sun responsible for global warming?

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #15 2025

- Renewables allow us to pay less, not twice

- Sabin 33 #23 - How much land is used for wind turbines?

- Our MOOC Denial101x has run its course

- 2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #14

- Fact brief - Is Mars warming?

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #14 2025

- Two-part webinar about the scientific consensus on human-caused global warming

- Sabin 33 #22 - How does waste from wind turbines compare to waste from fossil fuel use?

- Clean energy generates major economic benefits, especially in red states

- 2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #13

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #13 2025

- Climate skeptics have new favorite graph; it shows the opposite of what they claim

- Sabin 33 #21 - How does production of wind turbine components compare with burning fossil fuels?

- China will need 10,000GW of wind and solar by 2060

- 2025 SkS Weekly Climate Change & Global Warming News Roundup #12

- Skeptical Science New Research for Week #12 2025

- Climate Fresk - a neat way to make the complexity of climate change less puzzling

- Sabin 33 #20 - Is offshore wind development harmful to whales and other marine life?

- Do Americans really want urban sprawl?

Archived Rebuttal

This is the archived Intermediate rebuttal to the climate myth "Electric vehicles have a net harmful effect on climate change". Click here to view the latest rebuttal.

What the science says...

|

Electric vehicles have lower lifecycle emissions than traditional gasoline-powered cars because they are between 2.5 to 5.8 times more efficient, and are essential to reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. |

EVs are essential to reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and the use of fossil fuels that cause those emissions1 (also Singh et al. 2023). The Environmental Protection Agency has found that EVs typically have lower lifecycle emissions than traditional gasoline-powered cars, even when taking into account the emissions released when manufacturing EVs and generating power to charge them.2 The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has further explained that “[t]he extent to which EV deployment can decrease emissions by replacing internal combustion engine-based vehicles depends on the generation mix of the electric grid although, even with current grids, EVs reduce emissions in almost all cases.”3 The key reason why EVs reduce emissions in almost all cases is that they are inherently more efficient than conventional gasoline-powered vehicles: EVs convert over 77% of electrical energy to power at the wheels, whereas conventional vehicles only convert roughly 12%–30% of the energy in gasoline to power at the wheels.4

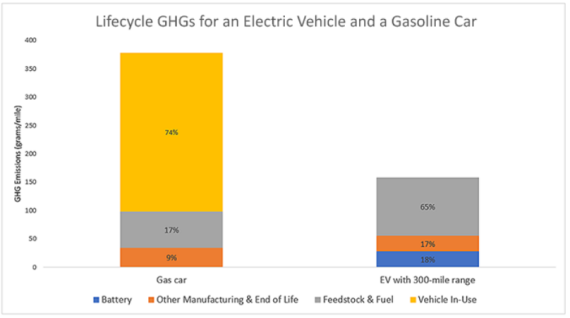

Assuming average U.S. grid emissions, the average lifecycle GHGs associated with a gasoline-powered car that gets 30.7 miles per gallon are more than twice as high as those of an EV with a 300-mile range.2 The figure below from the EPA shows that the lifecycle GHGs for the gasoline-powered car under this scenario are between 350 and 400 grams/mile, whereas the lifecycle GHGs for the EV are only slightly above 150 grams/mile.

Figure 17: Break down of lifecycle emissions for electric and gasoline cars. This figure is based on the following assumptions: a vehicle lifetime of 173,151 miles for both the EV and gas car; a 30.7 MPG gas car; and U.S. average grid emissions. Source: EPA.

Most importantly, EVs’ lack of tailpipe emissions and heightened efficiency more than offset the emissions required to manufacture EV batteries: these emissions are offset within 1.4-1.5 years for electric sedans, and within 1.6-1.9 years for electric SUVs5 (Woody et al. 2022). These reduced tailpipe emissions not only help to stabilize our climate, but also improve air quality, bringing multiple health benefits including reduced rates of childhood asthma, particularly in urban areas.

The emissions offset by transitioning to EVs vary based on the carbon intensity of the energy grid. A study from Munich’s Universität der Bundeswehr found EVs to have reduced emissions by 72% when powered by Germany’s electric grid, which drew 23% of its electricity from renewable energy in 2021 (Buberger et al. 2022). But the researchers projected that a 100% renewable energy grid would have allowed EVs to reduce emissions by as much as 97% (Buberger et al. 2022, Wolfram et al. 2021). And the U.S. grid is getting cleaner over time, with a 44% reduction in power sector emissions from 2005 to 2023, meaning that EVs are having an increasingly positive impact on U.S. emissions.6 For those drivers in the United States who would like to ensure that they are charging their EVs with the cleanest possible energy, the Environmental Protection Agency’s Energy Star program helps drivers determine which chargers rely on renewable energy sources.7

Footnotes:

[1] Electric Vehicle Benefits and Considerations, Alternative Fuels Data Centre, Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, US Department of Energy, (last visited Apr. 1, 2024).

[2] Electric Vehicle Myths, Envt’l Protection Agency (last updated Aug. 28, 2023).

[3] IPCC AR6 WGIII, Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change (2022), Chapter 2.8.3.2

[4] All-Electric Vehicles, U.S. Dept. of Energy; see also Eric Larson et al., Net-Zero American: Potential Pathways, Infrastructure, and Impacts: Final Report, Princeton University, 247 (Oct. 29, 2021) at 40.

[5] These figures assume “a business-as-usual scenario which includes policies in place as of June 2020 with no projected policy changes, resulting in a grid that is 50% less carbon intensive in 2035 compared to 2005.”

[6] Power Sector Carbon Index, Scott Institute for Energy Innovation (last visited March 25, 2024).

[7] Charge Your Electric Vehicle Sustainably With Green Power, Energy Star, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, 2 (last visited March 25, 2024).

This rebuttal is based on the report "Rebutting 33 False Claims About Solar, Wind, and Electric Vehicles" written by Matthew Eisenson, Jacob Elkin, Andy Fitch, Matthew Ard, Kaya Sittinger & Samuel Lavine and published by the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School in 2024. Skeptical Science sincerely appreciates Sabin Center's generosity in collaborating with us to make this information available as widely as possible.

Updated on 2024-09-02 by Ken Rice.

THE ESCALATOR

(free to republish)