A worse-than-current-policy world?

Posted on 21 April 2025 by Zeke Hausfather

This is a re-post from The Climate Brink

The world has made real progress toward tacking climate change in recent years, with spending on clean energy technologies skyrocketing from hundreds of billions to trillions of dollars globally over the past decade, and global CO2 emissions plateauing.

This has contributed to a reassessment of likely climate outcomes this century, with the world now likely heading toward less than 3C warming by 2100 under current policies – compared to the 4C warming that seemed more plausible 15 years ago.1

However, it is important to emphasize that current policies are neither a ceiling nor a floor on future emissions. While I hope that recent trends in declining clean energy cost, rapid deployment, and stronger climate policy trends accelerate in the coming decades, it is by no means assured.

Below the surface of cautious optimism lurks a much darker potential future, one where clean energy is curtailed not by a lack of human ingenuity but by misguided policy that priorities and subsidizes domestic fossil energy resources while closing us off from the rest of the world.

Enter SSP3

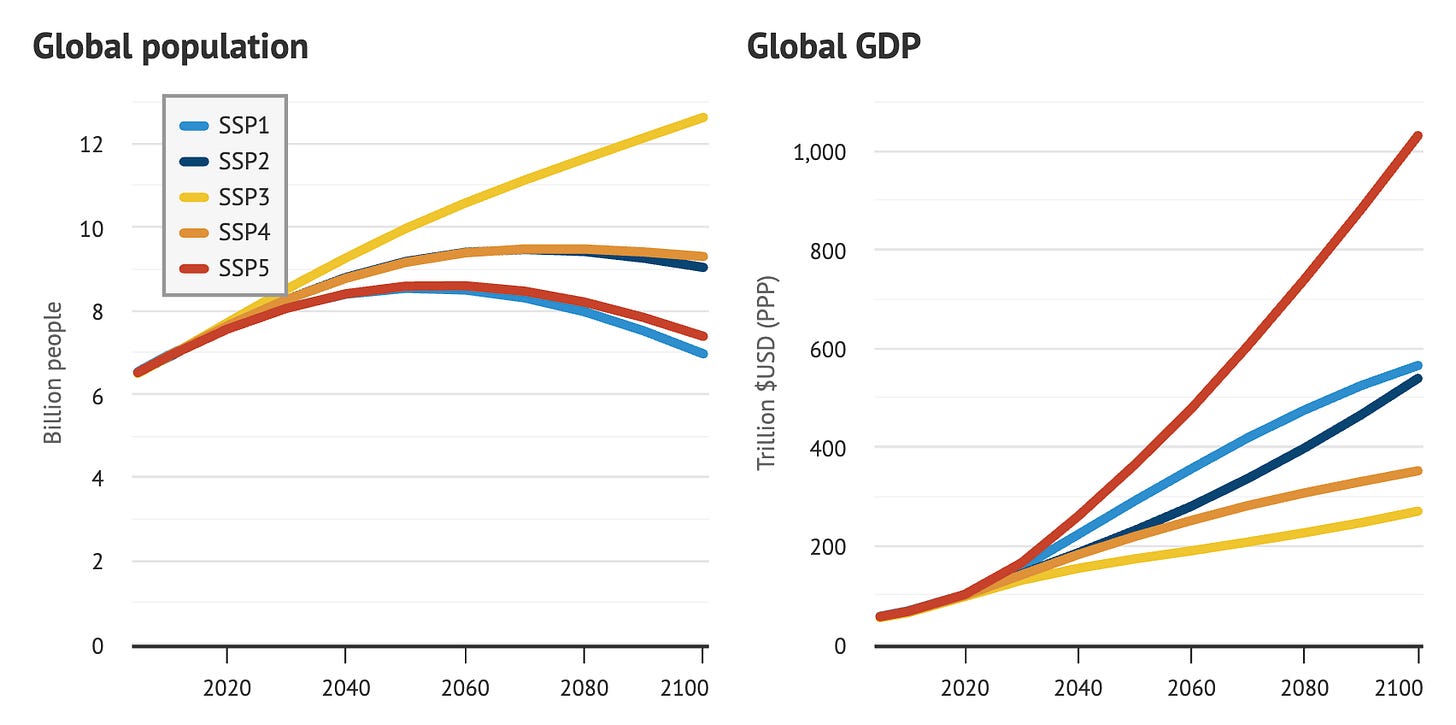

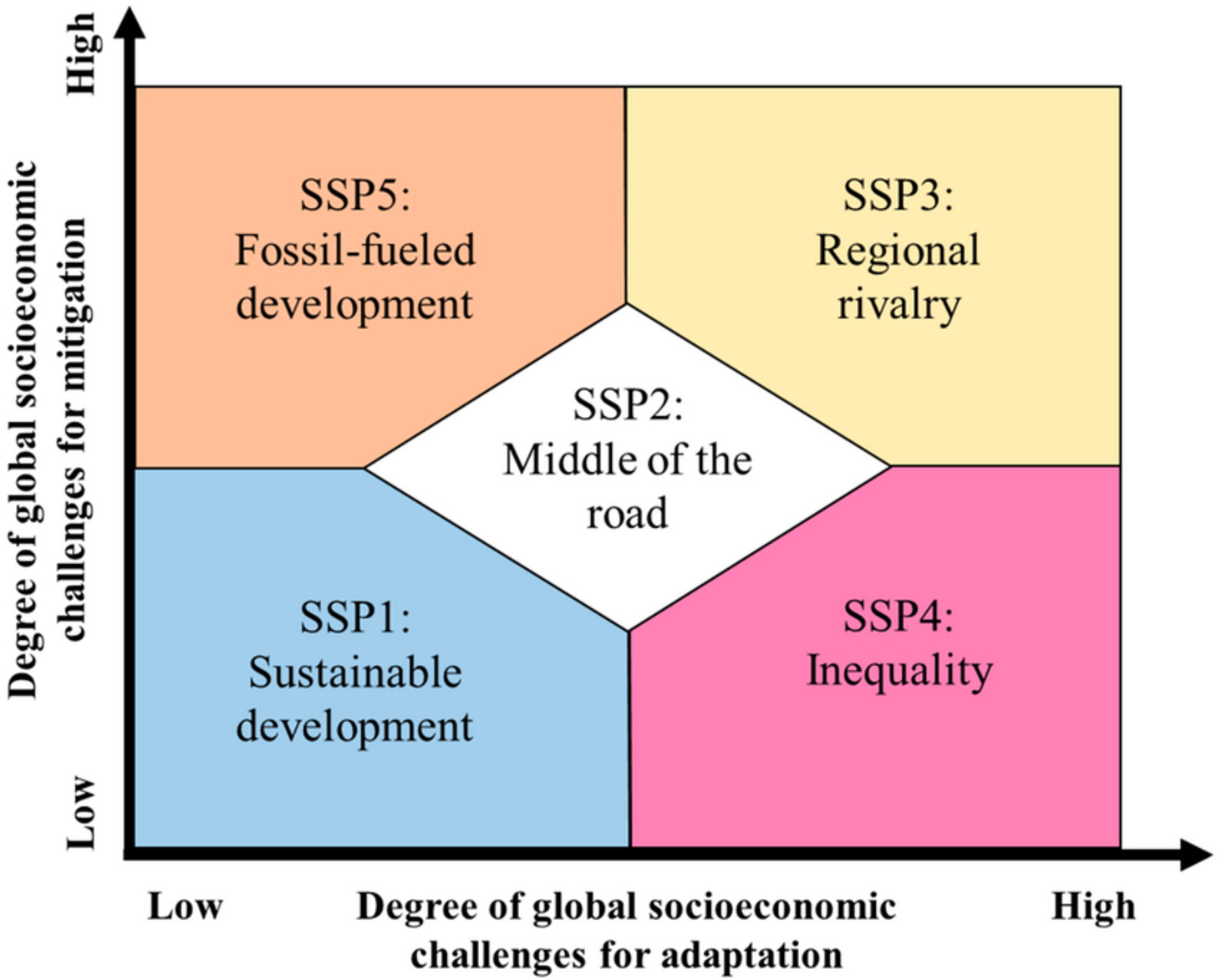

Back in 2016, the global energy modeling community set out to explore a set of socioeconomic futures that could shape the 21st century, impacting both our emissions and our ability to mitigate and adapt to climate change. They produced five different “Shared Socioeconomic Pathways”, or SSPs, that involved different underlying narratives of the future, levels of economic and population growth, and barriers to international cooperation and technological development.

These SSPs included a equitable, sustainability-focused world of SSP1, a current-trends-continue SSP2 world, a world of high inequality (SSP4), and a world of rapid growth drawing heavily on fossil fuels (SSP5). But the world with the worst damages from climate change combined high inequality, high emissions, and low economic growth. It was called SSP3, and in many ways it reflects a current strain of populist isolationist politics that is ascendent today:

SSP3 - Regional Rivalry – A Rocky Road (High challenges to mitigation and adaptation)

A resurgent nationalism, concerns about competitiveness and security, and regional conflicts push countries to increasingly focus on domestic or, at most, regional issues. Policies shift over time to become increasingly oriented toward national and regional security issues. Countries focus on achieving energy and food security goals within their own regions at the expense of broader-based development. Investments in education and technological development decline. Economic development is slow, consumption is material-intensive, and inequalities persist or worsen over time. Population growth is low in industrialized and high in developing countries. A low international priority for addressing environmental concerns leads to strong environmental degradation in some regions.

I even got in a bit of trouble back in 2021 by calling this “Trump World”, though the actions in his second term around energy and trade seem to be playing out much more closely to SSP3 than other pathways.

Despite having about 1C less overall warming than the (rather internally inconsistent and implausible) SSP5 pathway,2 SSP3 actually results in larger damages from climate change to society. Thats because in SSP3 the world is relatively poor and unequal; large parts of the planet still live in relative poverty without access to technologies that allow them to at least partially adapt to climate changes. The SSPs provide a useful tool to separate challenges to mitigation and adaption and more carefully explore the interplay of the two on future impacts.

That being said, the 21st century is much longer than a four year term, and the world is much larger than the United States. While a world like this is worth considering (and trying to avoid!), its far from a foregone conclusion that we are headed there now. And some changes over the past decade make the SSP3 baseline scenario less likely than when it was originally published.

Still an unlikely scenario

There are a few parts of SSP3 that seem pretty unlikely even if Trumpian politics become the driving force of the next 75 years. For one thing, global population growth as high as SSP3 is increasingly unlikely; even the decade since the SSPs were published has seen a notable downturn in future population projections.

Similarly, SSP3’s dramatic expansion of coal use seems pretty unlikely today. Since the publication of SSP3 the world’s energy landscape has dramatically changed, both due to the plummeting costs of renewables and storage and from the expansion of natural gas systems (particularly LNG infrastructure). While clean energy is ideologically polarized in the US, it is less likely to be in China, India, and the developing world who will in large part determine the world’s emissions trajectory this century. There the focus is on building out the lowest cost energy system – which today is increasingly clean.

But the consistent move toward lower emissions futures over the past decade should not make us overconfident that this trend will necessarily continue. It is only through hard work – innovation, policy, deployment – that emissions will come down, and it is certainly possible to imagine a world worse than current policies would imply, even if it is not clear that we are headed toward that world quite yet.

And, of course, current policies themselves lead to a world a bit below 3C warming, which is woefully insufficient to avoid potentially catastrophic impacts from climate change. In the critical time that we need to ramp up mitigation, we are starting to move in the wrong direction.

Arguments

Arguments

Comments