Do volcanoes emit more CO2 than humans?

What the science says...

| Select a level... |

Basic

Basic

|

Intermediate

Intermediate

| |||

|

Humans emit 100 times more CO2 than volcanoes. |

|||||

Climate Myth...

Volcanoes emit more CO2 than humans

"Human additions of CO2 to the atmosphere must be taken into perspective.

Over the past 250 years, humans have added just one part of CO2 in 10,000 to the atmosphere. One volcanic cough can do this in a day." (Ian Plimer)

At a glance

The false claim that volcanoes emit more CO2 than humans keeps resurfacing every so often. This is despite debunkings from bodies like the United States Geological Survey (USGS). Such claims may be easy to make, but they fall apart once a little scientific scrutiny is applied. So, to settle this once and for all, let's venture out into the fascinating world of geology, plate tectonics and volcanism.

According to the USGS, there are 1,350 active volcanoes on Earth at the moment. An active volcano is one that can erupt, even if it's decades since it last did so. As of June 2023, 48 volcanoes were in continuous eruption, meaning activity occurs every few weeks. Out of those, around 20 will be erupting on any particular day. Several of those will have erupted by the time you have finished reading this.

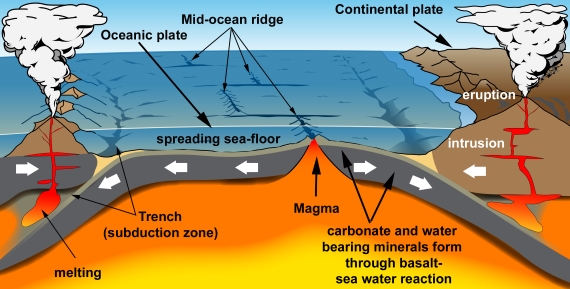

People are familiar with a typical volcano, an elevated area with one or more craters or fissures from which lava periodically erupts. But there are also the submarine volcanoes such as those along the mid-oceanic ridges. These vast undersea mountain ranges are a key component of Earth's Plate Tectonics system. The basalts they continually erupt solidify into the oceanic crust making up the flooring of the deep oceans. Oceanic crust is constantly moving away from any mid-ocean ridge in the process known as 'sea-floor spreading'.

Oceanic crust is chemically reactive. It reacts with seawater, allowing the formation of huge quantities of minerals including those carrying carbon in the form of carbonate. But oceanic crust is geologically young. That is because it is also being consumed at subduction zones - the deep ocean 'trenches' where it is forced down into Earth's mantle.

When oceanic crust is forced down into the mantle at subduction zones, it heats up and begins to melt into magma. Carbonate minerals in that crust lose their carbon - it is literally cooked out of them. Magmas then transport the CO2 and other gases up through Earth's crust and if they reach the surface, volcanic eruptions occur and the CO2 and other gases leave the magma for the atmosphere.

So here you can see a long-term cycle in which carbon gets trapped in the sea-floor, subducted into the mantle, liberated into new magma and erupted again. It's a key part of Earth's Slow Carbon Cycle.

Volcanoes are also dangerous. That's why we have studied them for centuries. We have hundreds of years of observations of all sorts of eruptions, at Earth's surface and beneath the oceans. Those observations include millions of geochemical analyses of both lavas and gases.

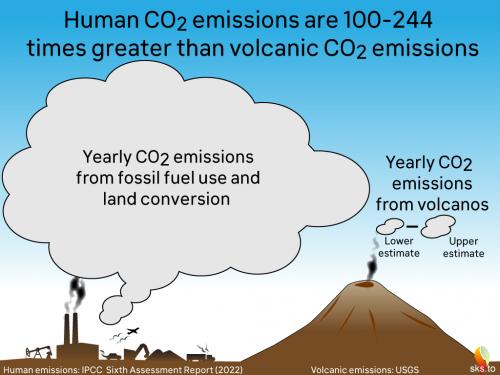

Because of all of that data collected over so many years, we have a very good idea of the amount of CO2 released to the atmosphere by volcanic activity. According to the USGS, it is between 180 and 440 million tons a year.

In 2019, according to the IPCC's Sixth Assessment Report (2022), human CO2 emissions were:

44.25 thousand million tons.

That's at least a hundred times the amount emitted by volcanoes. Case dismissed.

Please use this form to provide feedback about this new "At a glance" section. Read a more technical version below or dig deeper via the tabs above!

Further details

Beneath the surface of the Earth, in the various rocks making up the crust and the mantle, is a huge quantity of carbon, far more than is present in the atmosphere or oceans. As well as fossil fuels (those still left in the ground) and limestones (made of calcium carbonate), there are many other compounds of carbon in combination with other chemical elements, making up a range of minerals. According to the respected mineralogy reference website mindat, there are 258 different valid carbonate minerals alone!

Some of this carbon is released in the form of carbon dioxide, through vents at volcanoes and hot springs. Volcanic emissions are an important part of the global Slow Carbon Cycle, involving the movement of carbon from rocks to the atmosphere and back on geological timescales. In this part of the Slow Carbon Cycle (fig. 1), carbonate minerals such as calcite form through the chemical reaction of sea water with the basalt making up oceanic crust. Almost all oceanic crust ends up getting subducted, whereupon it starts to melt deep in the heat of the mantle. Hydrous minerals lose their water which acts as a flux in the melting process. Carbonates get their carbon driven off by the heating. The result is copious amounts of volatile-rich magma.

Magma is buoyant relative to the dense rocks deep inside the Earth. It rises up into the crust and heads towards the surface. Some magma is trapped underground where it slowly cools and solidifies to form intrusions. Some magma reaches the surface to be erupted from volcanoes. Thus a significant amount of carbon is transferred from ocean water to ocean floor, then to the mantle, then to magma and finally to the atmosphere through volcanic degassing.

Fig. 1: An endless cycle of carbon entrapment and release: plate tectonics in cartoon form. Graphic: jg.

Estimates of the amount of CO2 emitted by volcanic activity vary but are all in the low hundreds of millions of tons per annum. That's a fraction of human emissions (Fischer & Aiuppa 2020 and references therein; open access). There have been counter-claims that volcanoes, especially submarine volcanoes, produce vastly greater amounts of CO2 than these estimates. But they are not supported by any papers published by the scientists who study the subject. The USGS and other organisations have debunked such claims repeatedly, for example here and here. To continue to make the claims is tiresome.

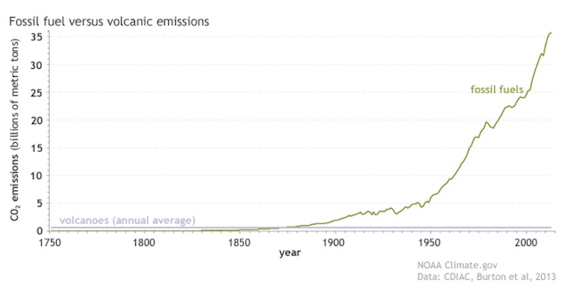

The burning of fossil fuels and changes in land use results in the emission into the atmosphere of approximately 44.25 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide per year worldwide (2019 figures, taken from IPCC AR6, WG III Technical Summary 2022). Human emissions numbers are in the region of two orders of magnitude greater than estimated volcanic CO2 fluxes.

Our knowledge of volcanic CO2 discharges would have to be shown to be very mistaken before volcanic CO2 discharges could be considered anything but a bit player in the current picture. They have done nothing to contribute to the recent changes observed in the concentration of CO2 in the Earth's atmosphere. In the Slow Carbon cycle, volcanic outgassing is only part of the picture. There are also the ways in which CO2 is removed from the atmosphere and oceans. If fossil fuel burning was not happening, the Slow Carbon Cycle would be in balance. Instead we've chucked a great big wrench into its gears.

Some people like classic graphs, others prefer alternative ways of illustrating a point. Here's the graph (fig. 2):

Fig. 2: Since the start of the Industrial Revolution, human emissions of carbon dioxide from fossil fuels and cement production (green line) have risen to more than 35 billion metric tons per year, while volcanoes (purple line) produce less than 1 billion metric tons annually. NOAA Climate.gov graph, based on data from the Carbon Dioxide Information Analysis Center (CDIAC) at the DOE's Oak Ridge National Laboratory and Burton et al. (2013).

And here's a cartoon version (fig. 3):

Fig. 3: Another way of expressing the difference between current volcanic and human annual CO2 emissions (as of 2022). Graphic: jg.

Volcanoes can - and do - influence the global climate over time periods of a few years. This is occasionally achieved through the injection of sulfate aerosols into the high reaches of the atmosphere during the very large volcanic eruptions that occur sporadically each century. When such eruptions occur, such as the 1991 example of Mount Pinatubu, a short-lived cooling may be expected and did indeed happen. The aerosols are a cooling agent. So occasional volcanic climate forcing mostly has the opposite sign to global warming.

An exception to this general rule, however, was the cataclysmic January 2022 eruption of the undersea volcano Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha'apai. The explosion, destroying most of an island, was caused by the sudden interaction of a magma chamber with a vast amount of seawater. It was detected worldwide and the eruption plume shot higher into the atmosphere than any other recorded. The chemistry of the plume was unusual in that water vapour was far more abundant than sulfate. Loading the regional stratosphere with around 150 million tons of water vapour, the eruption is considered to be a rare example of a volcano causing short-term warming, although the amount represents a small addition to the much greater warming caused by human emissions (e.g. Sellitto et al. 2022).

Over geological time, even more intense volcanism has occurred - sometimes on a vast scale compared to anything humans have ever witnessed. Such 'Large Igneous Province' eruptions have even been linked to mass-extinctions, such as that at the end of the Permian period 250 million years ago. So in the absence of humans and their fossil fuel burning, volcanic activity and its carbon emissions have certainly had a hand in driving climate fluctuations on Earth. At times such events have proved disastrous. It's just that today is not one such time. This time, it's mostly down to us.

Last updated on 10 September 2023 by John Mason. View Archives

Arguments

Arguments

I enjoy it so when the agenda (funding) driven science of climatology states so much they know that just isn't so... or at least isn't all of the story. (snip)

The last twenty years have seen huge steps in our understanding of how, and how much CO2 leaves the deep Earth. But at the same time, a disturbing pattern has been emerging.

In 1992, it was thought that volcanic degassing released something like 100 million tons of CO2 each year. Around the turn of the millennium, this figure was getting closer to 200. The most recent estimate, released this February, comes from a team led by Mike Burton, of the Italian National Institute of Geophysics and Volcanology – and it’s just shy of 600 million tons. It caps a staggering trend: A six-fold increase in just two decades.

These inflating figures, I hasten to add, don't mean that our planet is suddenly venting more CO2.

Humanity certainly is; but any changes to the volcanic background level would occur over generations, not years. The rise we’re seeing now, therefore, must have been there all along: the daunting outline of how little we really know about volcanoes is beginning to loom large.

[RH] Read the comments policy for why you were snipped here.

For the remainder of your comment, please cite the actual research instead of just recounting. People here will want to check your sources.

Also, note that annual human emissions of CO2 are 30GT. That's about 30,000 million tons.

Prof X @276 fails to provide his reference for his claim of deep Earth degassing of CO2 of approx 600 million tonnes of CO2 per annum, and nor is a recent discussion of global geophysical degassing rates evidents from Burton's list of publications. In any event, the 600 million tonnes figure is a reduction from Burton's prior estimate (2013) of 937 million tonnes of CO2 per annum from all deep sources, discussed by me @256 (July, 2014) above. If Burton indeed has a new estimate of approx 600 million tonnes, that would be a reduction from his prior estimate, which would spoil Prof X's narrative.

To add slight confusion, Burton does have a 2014 conference paper which estimates a global flux of 1,800 million tonnes of CO2 based on new measurements of CO2 flux (still only 5% of anthropogenic emissions), but that estimate does not appear to have made it into a journal article. Further, as more recent direct measurements of CO2 flux from a volcano contradict the claims heightened flux from Burton's indirect measurements, the premise of the 2014 conference paper estimate appears to have been falsified.

i came across Wylie's article the other day. Interesting. The other point he covered was diffuse CO2, that is invisible, i.e. not associated with steam plumes, part of the reason for upping the estimates, but more importantly that some we thought extinct are invisibly emitting CO2 adding perhaps another 50%, which would take CO2 to ~1 billion tons a year, 10 times what we thought 20 years ago, and therefore now around 3%, three times what was said at the beginning of the thread.

it occurred to me that as this gas was bubbling through the magma, the diffusion would seperate the C12 from C13 and that, depending on time, variation etc, could distort the ratio that we use for measuring anthropogenic emissions from fossil fuels, in the same direction, meaning we would overestimate anthropogenic by up to that amount.

Still small in the scheme of things but not insignificant, with obvious effects in rare of AGW and 2100 levels.

just a thought.

No relation to Roy btw!

Tony Spencer @278, the estimates of geological CO2 emissions are certainly in ferment at the moment. One factor is that we know that over the long term, CO2 concentrations are essentially stable. Specifically, the CO2 concentration either at glacial maximums, or interglacial peaks have not varied by more than a few ppmv relative to other glacial maximums or interglacials respectively, for 800,000 years. It follows that natural emissions are essentially in balance with natural uptake of CO2. As it stands, however, where estimates of CO2 uptake used to exceed estimates of emissions by about 50%, they are not dwarfed by them. That means there is a problem with one set of figures, or the other, or both. My suspicion is that currently the vulcanoligists are over counting, but assume the estimate of natural uptake is too low. It would remain the case that total geological contribution to atmospheric CO2 increase is essentially zero.

@Tom 280,

That would make sense Tom, simply because the primary regulator of atmospheric gasses is the biosphere. When glaciation events were the main way the biological function was reduced by covering a significantly large area of land with ice, then the geological emissions would exceed natural uptake. The trend reverses till enough ice melts to allow the natural uptake to reign supreme again. So one would expect this. It would bracket the atmospheric CO2 in a range. This is what we see for the last 800k years.

This would support the idea that the degrading biosphere and ecological systems caused by mankind are what has allowed fossil fuel emissions to force the atmosphere to exceed that bracketed range. (very roughly ~170 - 320 ppm +/-) The biological stabilizing feedback function has been degraded simulataneously with increased emissions. Either alone is probably not enough to upset the balance. But both together obvious is since we are watching it happen.

RedBaron @281, if the primary regulator of atmospheric CO2 is the biosphere, as you claim, covering vast swathes of that biosphere with land ice would reduce the fixing of CO2 into soil, and hence result in an increase in atmospheric CO2 durring glacials. Instead we see the reverse.

Although it is not yet entirely clear what drives the synchronous changes of pCO2 and GMST, the evidence strongly suggests the deep ocean has a major role. That role must be at least modulated by change in surface vegetation, which were extensive, even in the tropics. Specifically, the Sahara was not a desert (and much of the Australian outback was greened as well); but much land now covered with tropical rainforest was covered with grassland. The greening of the Sahara, however, survived several millenia past the start of the Holocene - so its contribution to pCO2 was minimal relative to the glacial/interglacial cycle. And total carbon sequestration in rain forest, per meter squared, exceeds that on grassland in every review I have seen, which would make that change, again, counter cyclical.

Suggested supplemental reading:

What Is Kilauea’s Impact on the Climate? by Emily Atkin, The New Republic, May 26, 2018

It's suggested here that man's contribution is about 30bn tons of CO2 annually. The Climate.gov website estimates it at 40bn tons.

The Katla volcano is currently out gassing at a rate of between 12 and 24 ktn a day. That equates to a mid range (18ktn) figure of 6.5bn tons a year. That's about 17% of what man's contributing.

It should get quite warm next year?

[DB] As has already been noted, your statements and maths are erroneous.

Per NOAA, and Burton et al 2013 (which subsumes the works of Gerlach 2011), human activities produce more than 60 times the amount of CO2 than do all the volcanoes in the world, combined.

Umm, 18,000 tons * 365 days is 6.6 million tons, not billion. You're off by a factor of 1000. So Katla gives off ~0.02% of what humans do.

With the recent tsunami from Anak Krakatoa, there seems to be an increase in discussions of CO2 emissions from volcanoes. I have read that the 1883 Krakatoa and 1816 Tamboora eruptions did not emit enough to affect global CO2 levels in ice core measuremnts.

What about the Yellowstone eruption 670,000 years ago? Do we have any measurements with enough resolution going that far back?

@ancient_nerd, There are ice core records from Antarctica which go back that far. See Luthi et al (2008) and Bereiter et al (2015). If you look at their figures you'll see that at around 670,000 years ago the CO2 levels were quite low, below 180 ppm.

Volcanic activity does often show up in ice cores, not as elevated CO2 levels, but as ash layers, and other geochemical effects. These ash layers are often used to synchronize the cores which come from different locations.

For Yellowstone activity that would most likely stay in the northern hemisphere, so that would show up in the Greenland ice cores. Unfortunately, the deepest (oldest) cores only go back to about 150,000 years ago. So your 670,000 year event wouldn't show up.

I think the big eruption at Yellowstone was 2.2my ago. Calculations in Gerlach 2010 would have that comparable to a year of human emissions.

According to a wikipedia article, the eruption I was thinking about was at 630ky Yellowstone_Caldera. The chart in David's link shows what looks like the end of a glacial period right about then.

Ancient Nrd,

I don't see a change in CO2 at 630 kyr.

It appears to me to be the start of a glacial period.

Ancient Nerd: Sorry I mispelled your handle.

The source of the graph was Beretier et al linked by David Kirtley above.

michael sweet @290,

I see there was a paper presented a couple of years ago attributing the Yellowstone events of 630ky bp with dropping SSTs by 3ºCa couple of times for "at least ~80 yrs" which is longer than expected for a volcanic event (they speculate that feedbacks lengthened it) but it is not very long on a graph of 800ky of climate (about a tenth the width of a pixel in your diagrm).

There is media reports of the paper on-line but they don't say much more than the paper's abstract. The full text is available but on request.

MARodger,

You cite an interesting paper. It appears to me that volcanic dust and gas caused a winter effect. This is known from recent eruptions. Apparently the effect was longer than might be expected from a volcano.

In any case, the cooling effect is not caused by CO2 release. I think Ancient Nerd was asking if the volcano could have contributed to an increase in global temperatures from release of CO2. It appears to me that an increase in temperature from the CO2 did not occur. The amount of CO2 released was not measurable in the ice record. This demonstrates that release of CO2 from volcanoes, even extraordinarily large ones, does not affect climate.

michael sweet@290

The time scale on this chart seems to run backward from what we would expect intuitively. The left edge is the present, the right edge is 800k years ago. So, that large step around 625 or so is an increase in CO2 levels and temperature right about the time of the eruption.

As David pointed out earlier in post 287, there is no ash layer to provide accurate correlation since these cores come from antarctica in the southern hemisphere and the eruption was in the northern hemisphere. So we do not really know the exact timing.

Ancient Nerd,

I know the graph reads earlier on the left. There is a very large drop in CO2 at about 625ky. The bottom of the graph is lower CO2. There is no significant increase of CO2 anywhere near 630. Look at the graph again.

The dates are well established. You must cite a reference if you wish to challenge accepted science. There were 13 eruptions in the southern hemisphere in the last 200,000 years to date the ice. It appears that you are just making things up to suit your preconceived notions.

This data shows that CO2 from the Yellowstone volcano did not affect world wide CO2 concentrations.

I am not denying the science. I am just wondering if what we have here is really conclusive. Thank-you for taking the time for a curious amateur.

So that big rise from 200 to 240 ppm really is at 620 or 625. Is the time calibration really so good that we can be sure the Yellowstone eruption happened earlier? It seems possible that the little wiggle we might expect is getting blasted away by a much bigger signal.

michael@295

Maybe you should look at the graph again. 650k years ago, the CO2 is at 200 ppm. 35,000 years later, at 615k, the CO2 has increased to 240 ppm. That is a big increase at 625k.

The Gerlach 2010 calculation still stands. The amount of CO2 an eruption can produce is constrained by the solubility of CO2 in magma. This is a hard limit.

Ancient Nerd:

In fact I did read the graph incorrectly.

The increase in CO2 is still about 10,000 years after the eruption date.

Reading more background information, I found several articles (BBC Forbes GOOGLE search) that mentioned volcanic winters caused by supervolcanoes but none that mentioned CO2 effects. Several mentioned the Santa Barbara study referenced up thread. The Forbes article suggested that the supervolcano might have delayed the interglacial that was beginning around that time.

I see no supporting information for the idea that CO2 from the volcano caused an increasse in global temperatures.

michael sweet@299

so, the Santa Barbare study does put the end of the glacial about 10,000 years after the eruption. If there was any change in CO2 levels, it would be a tiny blip that may or may not barely stick out of the noise.

I am not sure if I can link to a specific yahoo comment of mine, but here is a paste from this article Anak Krakatau Volcano Erupts in Indonesia.

Measurements from ice core samples show no significant change in CO2 levels after either the Krakatoa or the Tambora eruptions. Volcanoes do inject sulfur into the stratosphere that cools the climate for a few years until it drops out. CO2 has a much longer lifetime in the atmosphere. It takes geological processes thousands of years to stabilize carbon levels.

I could now add to that something like:

There was a massive eruption at Yellowstone 630,000 years ago. It caused massive destruction as it left ash deposits up to 600 feet thick over much of North America. If there was a change in CO2 levels from that, it is barely visible, if at all, in the ice cores.

Thank-you