Food Security: the first big hit from Climate Change will be to our pockets

Posted on 26 December 2012 by John Mason

"While the global community has committed itself to holding warming below 2°C to prevent “dangerous” climate change, the sum total of current policies—in place and pledged—will very likely lead to warming far in excess of this level. Indeed, present emission trends put the world plausibly on a path toward 4°C warming within this century."

Turn down the Heat - why a 4oC warmer world must be avoided

World Bank, 2012

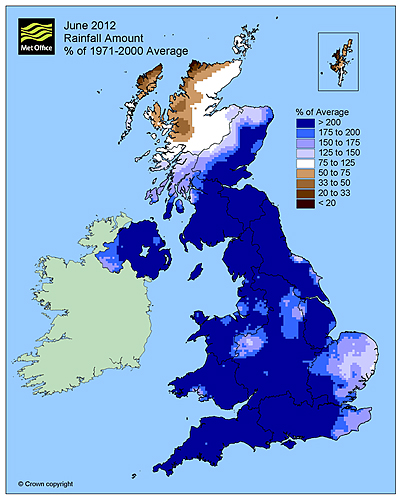

I've been growing a lot of my own food this past few years and amongst the varied challenges I've had to work around, the dismal summer of 2012 here in Wales has been the greatest of all. A cold and often overcast spring was followed by an exceptionally wet summer - the Met Office graphic for June (R) spells that out in no uncertain terms - and the few brief flickers of warmth that were felt early in the autumn came too late: the wind and rain soon set in again.

I've been growing a lot of my own food this past few years and amongst the varied challenges I've had to work around, the dismal summer of 2012 here in Wales has been the greatest of all. A cold and often overcast spring was followed by an exceptionally wet summer - the Met Office graphic for June (R) spells that out in no uncertain terms - and the few brief flickers of warmth that were felt early in the autumn came too late: the wind and rain soon set in again.

How did that affect the crops? Well, firstly, despite all sorts of control measures, including dead-of-night visits armed with a torch and bucket, the slugs had a field-day, chomping their way through anything they fancied. Slugs are always a nuisance to veg-growers, but the conditions this summer were just about perfectly in their favour. But there was more to it than that: the cold spring meant that the soil was slow to warm; bees and hoverflies, both vitally important to any grower, were both late to appear and in short supply and the severely reduced sunshine further compounded things. In short, it was a bit of a disaster!

Across the pond, conditions were the exact opposite with heat and prolonged drought affecting the American Midwest and severely reducing crop yields across vast swathes of normally productive land. It was as if the weather was stuck: wherever you were, if you had one type of weather, you were likely to be left with it for a long time. For growers, from my little one-man operation up to the big landowners, it's a bit like the Goldilocks story: you ideally need conditions to be 'just right', yet in both the cases I cite they weren't just off a bit - they were way off to one extreme or the other.

Skeptical Science has covered the recent research into the slowing and stalling of the Rossby Waves - the large upper ridges and troughs that trundle around the Northern Hemisphere from west to east and dictate the type of weather that goes on below. Evidence is accumulating that manmade global warming, at its greatest up in the Arctic (as demonstrated in no uncertain terms by the dramatic record sea-ice melt up there this year), has, by reducing the thermal gradient between the Arctic and the Tropics, affected the way in which these waves behave, and thereby caused weather-patterns to stall. Extreme weather does not have to just be about mile-wide EF-5 tornadoes: it can include weeks and weeks with no rain, or pretty much constant cloud and rain. And there is one early casualty of such conditions: agriculture.

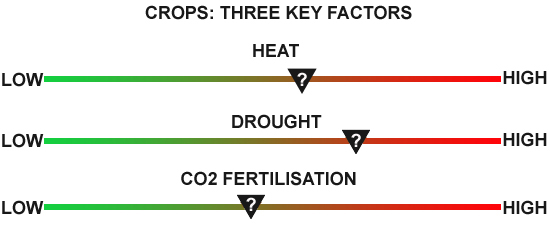

On exactly that topic, Oxfam released a report on September 5th 2012, entitled Extreme Weather, Extreme Prices, available here; now we have Turn Down the Heat - why a 4oC warmer world must be avoided, a report prepared by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) and Climate Analytics for the World Bank. Chapter 6 of the report looks at how future warming scenarios might further affect food security and it makes worrying reading. The report looks at the effects upon agriculture from three key perspectives: what they refer to as 1) the temperature-induced effect, 2) the precipitation-induced effect, and 3) the CO2-fertilization effect. There are other factors too: loss of biodiversity for instance can include loss of pollinating insects, which play an essential role in the reproduction of flowering plants. Given that very many types of fruit and veg fall into the 'flowering plants' category of plantlife, it is obvious that biodiversity is vitally important and we damage it at our peril. But let's look at the findings regarding the three factors above.

above: three key variables likely to affect crop yields in a warming world - but how?

Temperature

Since the release of the IPCC's AR4 in 2007, there have been significant developments in understanding the effects of temperature rises with respect to crop production. It's a mixed picture. Rising temperature may increase yields at higher latitudes where low temperatures are a limiting factor on growth. Conversely, at lower latitudes, increases in temperature alone are expected to reduce yields from grain crops because these mature earlier at higher temperatures, reducing the critical growth period and leading to lower yields, an effect that is well understood. Field experiments have, however, shown that crop sensitivity to temperatures has certain thresholds above which it takes off in a non-linear fashion (in other words these are tipping points beyond which crop-failure can be severe). Because, the report states, most current crop models do not account for this effect, with the very real risk of a 4oC world ahead of us, we need to overhaul the models to take these recent findings into account.

Precipitation

Recent projections and evaluations against historical records point to a substantially increased risk of severe drought affecting large parts of the world: currently affecting 15.4 % of global cropland, with 4oC of warming (relative to 1961-1990 temperatures) this could rise to a colossal 44 % by 2100. The regions expected to see increasing drought severity and extent over the coming decades are in southern Africa, the United States, southern Europe, Brazil, and Southeast Asia. Wetter conditions are projected in particular for the northern high latitudes: countries likely to be affected are those in northern North America, northern Europe (parts of which, i.e. the UK, have been in the news of late due to the severe floods they have had to endure) and Siberia, plus some monsoon regions.

CO2 Fertilisation

The effects of increasing atmospheric CO2 concentrations on crop yields are, the report states, one of the most critical assumptions with respect to biophysical crop modeling. It is critical because if the effects of CO2 fertilization can occur to the extent assumed in laboratory studies, then global crop production could - possibly - be increased; if not, then a decrease is possible. Thus, it's not a straightforward picture (although those who oppose mainstream science like to repeat 'CO2 is plant-food' as though they were chanting at a football match). A key constraint of the carbon fertilization effect on the ground (and not in the controlled conditions of a greenhouse or laboratory) is that it would be operating in situations where other variables, essential to plant growth, may not play ball. It's a long list when one includes all the various minerals and trace-elements but key factors are major nutrients such as phosphorus, potassium, nitrogen and so on. CO2 is plant-food but so are these elements and they are essential, as any serious vegetable-grower will tell you.

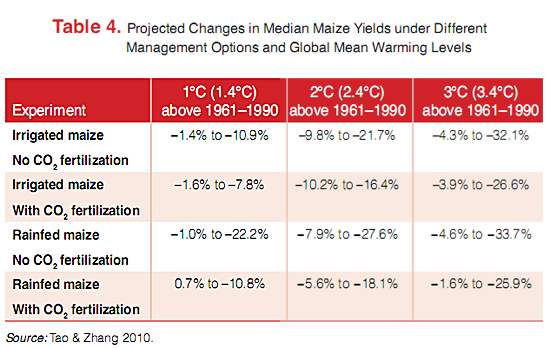

The table below (redrawn to fit our format) shows the results of a study on maize in China, and it illustrates an example of the way in which these three factors interplay - it's not a simple picture. Note that projected temperature figures in brackets are above the pre-industrial average and those not in brackets are above the 1961-1990 average.

Even with carbon dioxide fertilisation, yields tend to be reduced, with the possibility of severe reduction. Other factors that may have some success in mitigation of the worst effects are the production of new cultivars that have better resistance to heat or water stress, or resilience to plant pathogens that favour certain conditions: I may well be trying the new blight-resistant potato cultivars that are emerging if I can get hold of any, as our damp Welsh summers in recent years have seen major outbreaks of this devastating fungus.

Alternatives?

And what of the warming northern latitudes? Some argue that if we lose the USA Midwest then we simply shift production northwards. It ain't that simple, folks. Yes, in time one would be able to grow crops in areas that are currently thawing permafrost. But there's one thing you need to grow fruit and veg productively: healthy soils. And that's the problem: healthy soils take a considerable time to develop. The problem is not the end result in a few centuries' time (assuming things reach an equilibrium state by then): the problem is the period of transition from now to then, in which events may move at a pace beyond our ability to keep up, to adapt.

Consequences

The first noticeable effect of reduced crop yields is already manifesting itself in rising food prices:

According to the Food and Agriculture Organisation in Rome, global wheat production is expected to fall 5.2% in 2012 and yields from many other crops grown to feed animals could be 10% down on last year.

"Populations are growing but production is not keeping up with consumption. Prices for wheat have already risen 25% in 2012, maize 13% and dairy prices rose 7% just last month. Food reserves, held to provide a buffer against rising prices, are at a critical low level. It means that food supplies are tight across the board and there is very little room for unexpected events," said Abdolreza Abbassian, a senior economist with the FAO. (source: Guardian, October 2012)

above: a few of the author's shallots nearing harvest-time, July 2010. With a lousy spring and summer due to weather-patterns getting 'stuck', 2012's crop was a sorry sight in comparison!

Food is one thing that cannot be regarded as a luxury (unlike a lot of consumerist 'stuff'). Any major hike in food prices places immense numbers of the world's poorest people under severe hardship or even starvation. At the same time, across the developed world, it hits all but a small percentage (the wealthy) as an unavoidable, universal tax, a big dent in the pocket. But rises to date have been relatively minor, when compared to what would be in the pipeline for a +4oC world.

Those who loudly oppose mainstream science like to pretend how we are being fleeced by all sorts of 'green taxes'. But you never hear a squeak from them about this one, the greatest, most far-reaching tax of all time, that if they get their way we will all have to pay. The alternative is to starve: it's not much of a choice really, is it?

So the World Bank joins the academic institutions of every country worldwide, the world's military, the International Energy Agency and the United Nations. Everyone, apart from a few noisy think-tanks and their shills and their disciples, realises that we are heading in the wrong direction; that what we are doing is far from being in the best interests of humanity. Four degrees of warming can - and must - be avoided.

Our leaders need to stop thinking about the next election, four or five years ahead, and take a longer-term outlook. This is happening on their watch and the worse things get - and let's not forget that hikes in staple food costs were a factor in the emergence of the Arab Spring unrest - the less likely it is that they will be forgiven for failure to take action.

Postscript (30/12/2012):

Driving from the Midlands back to Mid Wales last week, it occurred to me that I ought to record the spectacular flooding along the River Severn for posterity; having done so it then occurred to me that the state of the ground was worth recording too. The photograph below was taken near Leominster in Herefordshire, but frankly it could have been anywhere between Birmingham and the Welsh mountains as most fields looked similar. How one goes about planting in such conditions is anybody's guess!

Arguments

Arguments

Klapper,

If you wish to continue your discussion of crop yields they would be on topic on this thread. I read the reference you cited in your deleted post. If the best that you can find in the peer reviewed literature is a paper from Bulgaria written in 2000 I suggest that you are way out of date. (Although Bulgaria might be far enough north to benefit from the warming so far). The citations that I quoted from the IPCC report are up to date and claim world wide decrease in yield of wheat and maize (corn). I am also unimpressed with your claims that you eyeballed the data and found a different result. Can you find more recent citations that support your claims?