The Mid-Wales floods of June 2012: a taste of things to come?

Posted on 20 July 2012 by John Mason

Sitting on the western side of a landmass that already juts out prominently into the Atlantic, facing into the prevailing moist sou-westerlies and having lots of high ground just set back from the coast, Wales has a deserved reputation for having a wet climate. It is generally a very green country. Not all the time, it must be said: the summer of 2006 was marked by a drought so severe that farmers ended up having to cut sections of fence to allow stock to access what springs were still flowing, and it was the year in which a farmer friend was one of many who decided to have a borehole drilled as a new and more reliable water supply.

I've lived here in Mid-Wales for over 30 years now and having a strong interest in meteorology I've investigated all sorts of severe weather, from the Great Blizzard of 1982 to the EF-2 tornado that tore a path of destruction through a neighbouring village late in 2006. I've seen the aftermath of flash floods following severe thunderstorms and have even chased the occasional supercell. But I don't think any of these events have been so shocking as the Mid-Wales floods of June 8-9 2012.

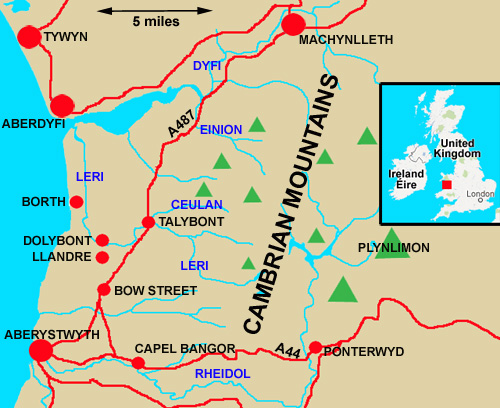

above: map of the area of Wales affected by the floods of June 8-9, 2012. Green triangles are summits, the highest of which is Plynlimon (752m). Large red circles are towns; small ones are villages. Roads are in red; rivers in blue. Graphic: author

Rain set in early on Friday June 8th as a deep area of low pressure off the SW of England moved NE straight across Wales. By the evening of the 8th, the low had moved off into the North Sea, but an associated trailing occluded front continued to sit over Mid-Wales overnight before finally drifting off northwards later on Saturday June 9th. The rain finally died out late morning on the 9th, almost 36 hours after it started.

This was a classic dynamic rainfall event: south-west winds with a long fetch down across the warm Atlantic brought moisture with them, only for it to fall out as rain when the air cooled as it was forced up over the Cambrian Mountains, generally 500-600m in height. It was a classic example of “warm conveyor” driven, orographically-enhanced rainfall, made more efficient by the 'seeder-feeder' mechanism in which ice crystals falling from high, upper clouds seed the moist layers below.

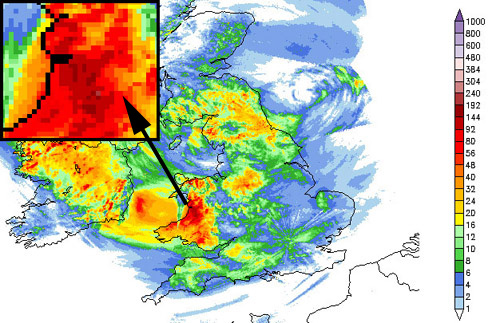

However, what made this event stand out from the rest was the incredible 36-hour event totals. Now, in winter we commonly see dynamic, warm conveyor rainfall events giving 75-100mm of rain over, say, 48 hours due to the aforementioned mechanism. Three to four inches of rain in that timespan may sound a lot but the area's geography deals with it effectively: peat-bogs soak a lot up and the remainder runs off, putting streams in spate and the major rivers such as the Dyfi and the Rheidol spill out over their flood-plains as they have done for thousands of years. A few roads are closed for a couple of days then everything goes back to normal. But this fall was different. The highest rain-gauge total I have seen was 183mm in 36 hours, but cumulative radar plots indicate that in some areas of higher ground, 200-250mm or eight to ten inches of rain fell during the event.

above: cumulative radar rainfall totals for day one of the event, Friday June 8th 2012, from Netweather. The inset (top L) is a zoom-in on the Mid-Wales district.

The result was chaos on an unprecedented scale.

Talybont is a village some seven miles north of the seaside university town of Aberystwyth. There has long been a settlement here, with Bronze Age, Iron Age and Roman remains to be found in the vicinity, but the village expanded with the growth of the lead and silver mining industry, which reached a peak in the Nineteenth Century, a time from which many of the original houses date. Two rivers pass through the village and meet just downstream from it: the Leri and the Ceulan. The Leri is a medium-sized river, but the Ceulan is little more than a stream. Talybont's village green, with its two old coaching inns, the White Lion and the Black Lion, sits in between them. It last flooded in 1963 when heavy late winter rains brought major snow-melt, and it is said a major factor in the flooding was that a tree had become wedged underneath the bridge that carries the main A487 road over the Leri. In 1990, the bridge was enlarged with a bigger and higher arch.

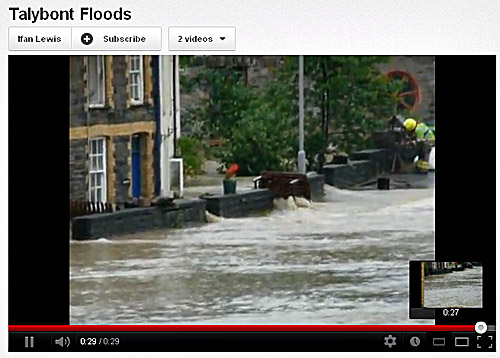

By the night of Friday June 8th, the Leri was already in raging spate, but early the following morning both the Leri and the Ceulan reached unprecedented levels. Water burst in through the backs of houses that had stood close to the Leri for at least two hundred years, flooding their ground floors feet deep. The Ceulan's waters tore across the car-park of the White Lion, ripping up metres of tarmac. The rivers merged together on the green and then as one surged on down the valley, where they overwhelmed flood defences with ease and swept across caravan sites, leading to emergency aerial evacuations taking place involving local lifeboat crews and RAF helicopters. At Dolybont, the Environment Agency's river-level gauge on the Leri went, quite literally, off the scale. From there, the floodwaters continued on down to affect the fishing village of Borth before reaching the open sea. Days later, boat crews out fishing reported finding slicks of floating debris from houses and caravans, several miles out to sea. This incident involved neither snowmelt or wedged trees: it was, plain and simple, the sheer amount of rain that fell.

above: chaos - after the flood's peak, looking upstream along the Leri in Talybont, on the afternoon of June 9th 2012. Photo: author

On July 11th 2012, the BBC reported that, according to the UK Government's Committee for Climate Change:

“Four times as many homes and firms risk flooding in the next 20 years if the UK does not prepare for climate change.”

Criticising the government for cutting funds for flood defences, the committee said that these will be needed more than ever if climate projections prove accurate. This news follows the publication of the US National Oceanic and Air Administration's (NOAA) annual state of the climate publication, in which a supplementary report looks at attribution and asks whether extreme weather events can be linked to climate change.

Weather is of course influenced by climate, so that if the climate changes in any way one would expect the weather to respond accordingly. The NOAA research looked at a number of extreme events and ran estimates of the likelihood of them happening in a world with pre-industrial CO2 levels. They found that with some events, climate change almost certainly had a role. The 2011 Texas heatwave was 20 times more likely to happen as a result of the climate change to date; warm winter extremes such as the second warmest November on record in the UK, in 2011, were now a staggering 60 times more likely to happen. Some events were more influenced, however, by other factors such as man-made infrastructure: the 2011 Thailand floods were cited as an example.

In the UK, climate contrarians tend to blame all severe floods on man-made infrastructure: concreting-over of soil, building on flood-plains and so on. Let the events of June 8-9 2012 be a lesson for them: the Leri and the Ceulan are upland rivers that drain boggy, acid moorland where there is barely a speck of concrete to be seen and only a few single-track roads giving access to farms. It is too early to take these disastrous floods and nail them firmly to the notice-board of climate change, given that such research is a time-consuming process, but the unprecedented ferocity of these floods begs the question, “is this a taste of what is to come?”

above: a taste of things to come? Screengrab of a video taken by Ifan Lewis of Talybont.

The question is partially answered by the Clausius-Clapeyron relation: put simply, this holds that in a warming trend, for every added degree Celsius the air can potentially hold 7% more water vapour. It therefore follows that moist air-masses, such as those advected towards the UK from the sub-tropical Atlantic, can become substantially moister in a warming world, leading to more intense rainfall-rates and increased event-totals. It is important to point out that prolonged, multi-day dynamic rainfalls have always been a feature of the Welsh climate as we are especially prone to 'warm-conveyor' synoptic setups - as are the mountains of Ireland, the Lake District and Western Scotland. What we need to watch out for in the coming years are any further indications of increases in intensity of precipitation during such events in any of these areas. The November 2009 flood disaster in Cockermouth, Cumbria may be another example: it was another classic “warm conveyor” which dropped huge amounts of rain over the Lakeland fells.

Moving from individual events to broader trends, whilst over the pond in the USA the heat records have been going down like ninepins, here in the UK the summer has been dismal, with the only records getting broken involving rainfall. Many areas have seen in excess of 200% of the average rainfall in June, based on 1971-2000 climatology. Why have we been stuck in a weather-rut for so long?

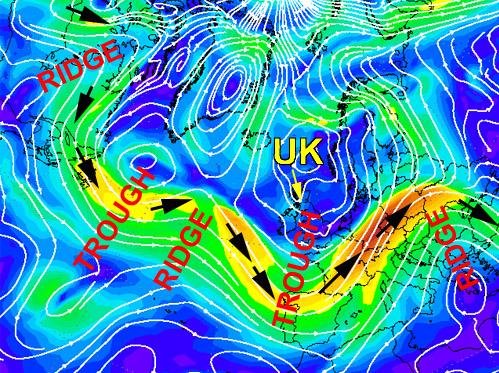

The answer lies in the large-scale waves that mark the course of the Polar Jet around the Northern Hemisphere. This band of strong winds aloft marks the boundary between the warmer air of the tropics and the colder air of the polar regions: upper ridges are where warm air has pushed northwards whereas upper troughs are where incursions of polar air are sinking southwards. The ridges bring warm, settled conditions in summer, whereas the troughs are where stormy weather is generated. And the problem - both for the USA and for the UK - has been that through June and July, the system got stuck.

above: GFS 300 hPa windfields over the North Atlantic for July 14, 2012. The Polar Jetstream is clearly marked as the band of stronger winds (green to red-orange) and the series of ridges and troughs is annotated. Chart from Wetterzentrale.

Typically, ridges and troughs migrate along this conveyor of west-to-east winds, but recent weeks have seen the stalling of this progression, so that the USA has been stuck beneath a strong upper ridge while the UK has been stuck under the influence of an upper trough. The result has been, for us, non-stop wet weather with a mixture of dynamic and convective rainfall bringing an abundance of costly flooding incidents. But why has this stalling occurred?

At Skeptical Science, we recently discussed a March 2012 paper by Jennifer Francis and Stephen Vavrus, published in Geophysical Research Letters. It is worth returning to this publication in the context of the current conditions. Francis and Vavrus looked at how these upper-level wave-patterns were responding to the well-documented changes taking place in the Arctic, where the warming trend is strongly enhanced in comparison to the rest of the planet, to the extent that it actually has a technical name - Arctic amplification. The warming has markedly reduced the thermal gradient between the Arctic and the tropics.

The work identified two key effects: firstly a reduction in zonality - the west to east movement - and secondly an increase in wave amplitude, meaning a tendency for ridges to push much further north and troughs to push much further south. Think of how a sluggish lowland river tends to develop meanders: if the jetstream slows down it, too, starts to meander a lot more. In combination, these two effects lead to some areas having prolonged periods of anticyclonic weather, bringing heat and increasing the risk of drought, and other areas having more prolonged periods of cyclonic weather, bringing excessive rainfalls and flooding.

Francis and Vavrus found the effects to be most evident in autumn and early winter, consistent with times of low sea-ice, but they also suggested that the same effect in summer could be caused by early snow-cover melt in high-latitude land areas. We have looked at long-reach teleconnection between the Arctic and Europe in early winter before: the extraordinary cold spell of December 2010 is often cited as an example of this process, with a block of high pressure over the Atlantic and prolonged northerlies bringing Arctic air south over the UK and elsewhere. Although forecast models suggest a return to a more mobile scenario soon, the question remains: was June-July 2012 an example of what we can expect in future when the system stalls in the warmer months?

The work of Francis and Vavrus and indeed other researchers in this field, for the research is ongoing, will be put to the test by what actually happens in the coming years. There is no reason to expect the Arctic amplification effect to cease (barring a miracle from policymakers), so that if they are right, we should see a continuing trend towards slow-moving, high-amplitude waves in the Northern Hemisphere. The weather-extremes caused by such patterns are problematic simply due to their prolonged nature. Drought, affecting many USA states, is one result. Saturated ground across parts of the UK (leading directly to rapid run-off from heavy rain and an increased flooding risk) is another. Both have large impacts on agriculture: in droughts, crop yields are poor, whilst in a saturated situation, plant diseases are more frequent and harvesting may be difficult or impossible. Both outcomes have major impacts upon food prices, so that if flooding hasn't hit you in the pocket then climbing food-prices will. Is this a taste of things to come? Because if it is, then global warming, left unmitigated, is going to be very expensive indeed.

Arguments

Arguments

0

0  0

0

Comments