2018 was the hottest La Niña year ever recorded

Posted on 24 December 2018 by dana1981

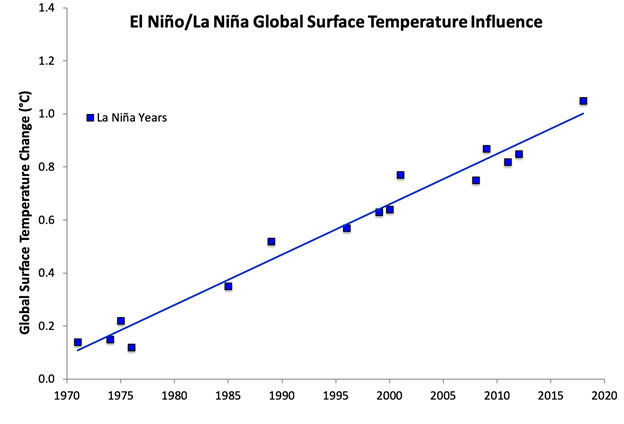

Once the final official global annual surface temperature is published, 2018 will be the hottest La Niña year on record, by a wide margin. It will be the fourth-hottest year overall, and the fourth consecutive year more than 1°C (1.8°F) hotter than temperatures in the late-1800s, when reliable measurements began. 2009 will be bumped to second-hottest La Niña year on record, at 0.87°C (1.6°F) warmer than the late-1800s, but about 0.16°C (0.29°F) cooler than 2018.

The above brief visual uses NASA GISS global average surface temperature data for 1970–2018, splitting the period into El Niño, Neutral, and La Niña years with linear trends. (Video by Dana Nuccitelli)

El Niño events bring warm water to the ocean surface; La Niña events are cool at the surface. Since scientists measure global surface temperatures over both land and oceans, new hottest year records are usually set during El Niño events.

For this reason, it’s best to compare like-with-like. In the case of 2018, given that it was a La Niña year, it’s most useful to compare it with prior years in which global surface temperatures were cooled by La Niña events.

NASA GISS global average surface temperature data for La Niña years during the period 1970–2018. (Illustration by Dana Nuccitelli)

NASA GISS global average surface temperature data for La Niña years during the period 1970–2018. (Illustration by Dana Nuccitelli)

Defining La Niña years

There is no established scientific definition of a “La Niña year.” To compare apples-to-apples, consider which years had similar surface temperature cooling influences resulting from La Niña events.

To do this, let’s examine the global temperature and El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) data since 1970. That’s the year the Clean Air Act was expanded to authorize regulation of sulfate pollutants that 1) are also released during the burning fossil fuels, and 2) offset global warming by blocking sunlight. Since 1970, emissions of those temperature-cooling pollutants have been reduced even as greenhouse gas levels have continued to rise. As a result, global warming has proceeded rapidly over the past five decades as the increasing greenhouse effect has been unmasked.

There are various indicators of El Niño and La Niña events. There’s the Multivariate ENSO Index (or MEI for short); the Southern Oscillation Index (SOI, which is counter-intuitive in that negative numbers indicate El Niño conditions); and the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI). For our purposes, let’s take the average of the three indices (accounting for the opposite sign of the SOI) and set a cutoff – years with an average index of ± 0.3 are El Niño or La Niña years, and values in the middle represent “neutral” years.

Let’s also separate out “volcanic years,” because large volcanic eruptions like El Chichón in 1982 and Mount Pinatubo in 1991 can release enough sulfate pollution into the atmosphere to significantly block sunlight and cool global surface temperatures for about three years.

Remember too that research scientists Grant Foster and Stefan Rahmstorf in a 2011 study estimated that there’s about a four-month lag before changes in the ENSO cycle are reflected in global surface temperature measurements. So, for example, ENSO changes from September 2017 through August 2018 influence the calendar year 2018 annual global surface temperature.

Using these criteria, since 1970 there have been 15 El Niño years, 15 La Niña years, 13 neutral years, and six volcanic years. 2018 was a fairly weak La Niña year similar to 2009 and 2012, but the global temperature was about 0.16-0.18°C (0.29-0.32°F) hotter in 2018 despite solar activity’s also remaining relatively low.

That last point is important: Those characterized as “climate contrarians” often argue either that the Sun is responsible for global warming, or that an extended quiet solar phase will trigger a “mini ice age.” The fact that record temperatures are occurring while the Sun is in a quiet phase dispels these claims, which have long been disproved by the climate science community.

The global warming trend is clear

The overall global surface warming trend over the past five decades is 0.18°C (0.32°F) per decade. The trends among just El Niño (0.19°C or 0.34°F per decade), neutral (0.17°C or 0.31°F per decade), and La Niña years (0.19°C or 0.34°F per decade) during that period are all very similar.

Arguments

Arguments

We had the slowdown in warming (such as it was, not very much) from about 1998 - 2014, then temperatures jumped from 2015 - 2016, and remain quite high even during a la nina. It looks like temperatures may be resetting at a permanently higher level. Speculation of course, but perhaps this is a sign of things to come, a very "step like" progression of warming, perhaps due to something to do with how ocean processes work.

Using 1970 as the year when the temperature anomaly emerged from the background noise as the starting point, plot the maximum atmospheric temperature for each decade (which is often the temperature of El Nino years), fit a line to it, and it parallels the line derived from fitting all of the atmospheric temperature data. Has there ever really been a slowdown if we look at the data over a long enough time period? The following plots merely shows that during large El Nino years that the temperature is about 0.2C higher than the long-term trend.

[DB] Reduced image width

The choice of Nina metrics seems a little arbitrary. Make different choices and 2017 is the warmest la Nina year.

http://origin.cpc.ncep.noaa.gov/products/analysis_monitoring/ensostuff/ONI_v5.php

Substantively, the point hardly alters, but the messaging is a little less compelling...

The fact that the La Niña of 2018 was warmer than the El Niño of 2010 and all El Niños from before is really telling.

2014 surprassed 2010 as the hottest year on record and it was a neutral year, and it looks like we probably won't get another year cooler than 2014 in our lifetimes, unless we get a really strong La Niña pretty soon.

Evan @2, yeah you are right. Looking at NASA GISS and the smoothed line, any slowdown was about 5 years at most around 2002 - 2007 and not dissimilar from previous slowdowns since 1970. Its obviously not significant. The long term smoothed line does form a step like pattern though, but nothing really radically different recently.

nigelj@5 I think the point that climate scientists like James Hansen have been making is that the energy continues to be pumped into the climate year after year, but because of the complex ocean circulation and El Nino/La Nino cycles, we just don't see it in the atmospheric temperature record as a smooth increase. I know you know that, but we have to keep reminding ourselves of this when focusing down on short-term trends.

Excellent, and well explained, however I think the problem is some scientists have denied there was a pause which is technically correct in energy accumulation terms etc, but the public see a clear slowdown or "pause" in surface temperatures from about 2002 - 2007 in the smoothing line in the nasa giss graphs, so the public get confused. You have to ackowledge there was a pause in surface temperatures, or it looks deceitful.

I remind people that the intermmitent slow periods of warming of a few years are just the influence of natural variation, and that the early IPCC reports predicted there would be slow warming periods of up to 10 years, due to the impact of natural variation. We have seen a couple so its exactly what was predicted! So the so called pause never bothered me.

nigelj@7 people who live in earthquake zones know that when there is a pause in earthquake activity that the big one might be coming. The energy keeps building up year after year, whether or not it is periodically released.