Addressing the Climate Crisis: Evolution or Revolution1

Posted on 4 March 2022 by Evan

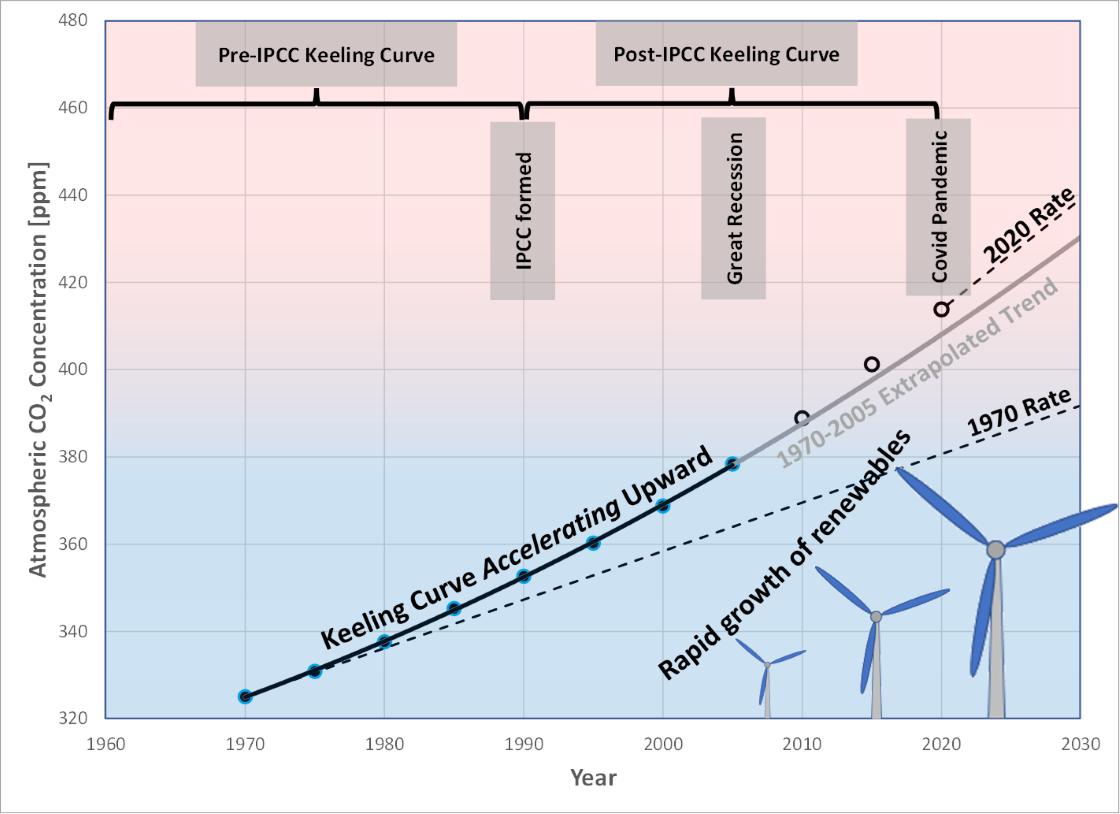

Many hope the planned explosion of renewable energy in the 2020’s will be the first significant step towards reaching Net-Zero by 2050 and stabilizing the climate. Similar hopes were expressed when emissions dropped during the Great Recession (read here) and the Covid Pandemic Lockdown (read here). But the Keeling Curve did not notice, showing great resiliency in the face of societal upheaval. Whatever temporary emission pauses excite us, the long-term trend of the Keeling Curve is a persistent, upward bent. To appreciate the scale of the problem, consider the following characteristics of this iconic curve.

Figure 1 shows the Keeling Curve plotted from 1970 to 2005. The data points represent 10-year averages of the raw data.2 Extrapolating the 1970-2005 trend line forward, the data points for 2010, 2015, and 2020 lie above this upward-accelerating trend line.3 This implies that the 1970-2005 extrapolated Keeling Curve does not accelerate upward fast enough to explain the 2010-2020 data. That is, despite the Great Recession, the rapid growth of renewables, and the Covid Pandemic, the acceleration itself seems to be increasing! The Keeling Curve seems not to appreciate any of our efforts to slow down its rapid, upward acceleration! What will it take to impress the Keeling Curve?

Figure 1. Keeling Curve plotted from 1970 to 2020 as 10-year averages from 1970 to 2015, and a single 3-year average to represent the 2020 data. A trend line is fit to the 1970 to 2005 data, and extrapolated forward to 2030 (shown as the solid, gray line). The 1970 and 2020 rates are shown as black, dashed lines.

If the rollout of renewables in the 2020’s is to have any chance of impressing the Keeling Curve, it needs your full support: in addition to replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy, we must consume less. Think about Fig. 1 the next time you ponder the future of your children and grandchildren, so that it helps you decide how to vote with your money and your politicians. Just as you should resist those who claim all is well, “live and be happy,” resist those who project a rosy future that only requires minor adjustments to how we live, while continuing unbounded economic growth.

If we are to tame the Keeling Curve (i.e., achieve Net-Zero by 2050), we must not only stop the upward acceleration of the Keeling Curve, we must stabilize the Keeling Curve to the same kind of horizontal line that formed the basis for the emergence of modern civilization.4 So far, nothing we’ve done has impressed the Keeling Curve. Nothing.

There is a saying, “If you do what you’ve always done, you’ll get what you've always got.”

Time to do things differently.

The future is revolution. Either we proactively revolutionize how we live, or we reactively bear the brunt of revolutionary climatic changes. Our choice.

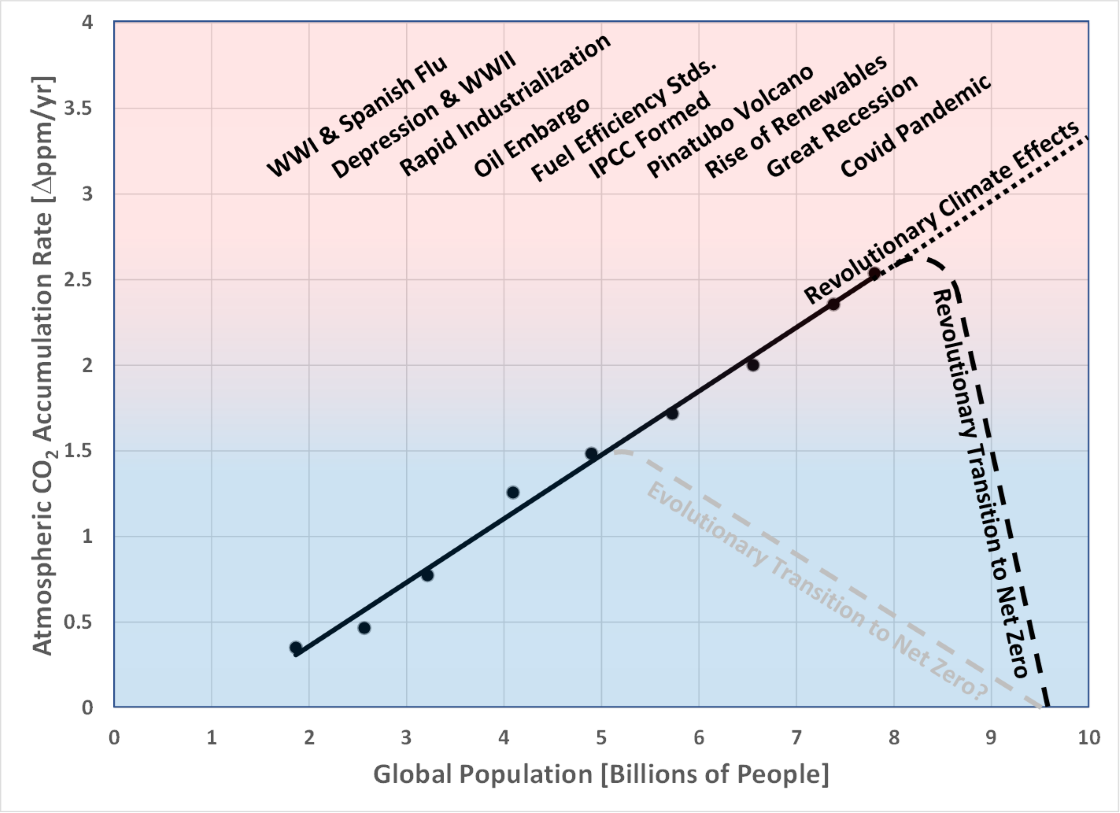

Lest you think that the problem can be easily remedied by reverting to an earlier nostalgic time when people pumped their own water, used an out-house by the barn, and did not have houses full of electronic gadgets sucking power, consider Fig. 2, which shows the annual rate of atmospheric CO2 accumulation vs global population. This plot goes back to the early 1900’s, and suggests a direct relationship between the number of people and the annual accumulation rate of CO2. There is no apparent difference in what they did versus what we’re doing. We’re just doing it on a grander scale. The upward trend seems to be ruled by one dominant factor: global population.

Figure 2 shows what the revolution needs to look like: a plunge down to achieve Net-Zero by 2050.5

Figure 2. Annual atmospheric CO2 accumulation rates vs global population. Various notable events are shown. The dashed lines show the trend towards Net-Zero we might have followed had we started immediately after the IPCC was formed, and the trend currently proposed. This figure implicitly assumes that we will reach a global population of 9.5 billion by 2050, the target year for achieving Net-Zero.

What will it take to break the incessant upward trend and drive annual CO2 accumulation to 0? As a minimum, it will take your full involvement, as well as the commitment of enough people to elect public officials who will stay the course. This is not a sprint to Net-Zero: it is a marathon.

Monitoring our approach to Net-Zero is conceptually easy. Just measure the CO2 concentration each year and see if it stops increasing. Read here for additional information about how to monitor our approach to Net-Zero. To be successful, we need to follow something like the following path.

As of 2021 we are at 415 ppm CO2 and rising 2.5 ppm/yr. Let’s assume that we immediately start decreasing this rate by 0.1 ppm/yr. That means something like the following trend, where in 2022 we first stop the rate of increase from increasing, and in 2023 we get the CO2 accumulation rate to start dropping by 0.1 ppm/year. This looks like the trend show in Table 1.

Table 1. Path to Net-Zero by 2050.

| Year | ?CO2 [?ppm/yr] | CO2 Conc [ppm] |

| 2021 | 2.5 | 415 |

| 2022 | 2.5 | 417.5 |

| 2023 | 2.4 | 420 |

| 2024 | 2.3 | 422.4 |

| 2025 | 2.2 | 424.7 |

| 2026 | 2.1 | 426.9 |

| 2027 | 2.0 | 429 |

| 2028 | 1.9 | 431 |

| 2029 | 1.8 | 432.9 |

| 2030 | 1.7 | 434.7 |

| 2031 | 1.6 | 436.4 |

| 2032 | 1.5 | 438 |

| 2033 | 1.4 | 439.5 |

| 2034 | 1.3 | 440.9 |

| 2035 | 1.2 | 442.2 |

| 2036 | 1.1 | 443.4 |

| 2037 | 1.0 | 444.5 |

| 2038 | 0.9 | 445.5 |

| 2039 | 0.8 | 446.4 |

| 2040 | 0.7 | 447.2 |

| 2041 | 0.6 | 447.9 |

| 2042 | 0.5 | 448.5 |

| 2043 | 0.4 | 449 |

| 2044 | 0.3 | 449.4 |

| 2045 | 0.2 | 449.7 |

| 2046 | 0.1 | 449.9 |

| 2047 | Net-Zero | 450 |

This path shown in Table 1 leaves us with 450 ppm CO2 in 2050, sufficient to take us to 2°C warming. Without getting into the details here (read here for the details), the actual path to Net-Zero by 2050 requires that we not only stabilize the Keeling Curve, but get it to start decreasing. If we do that, then theoretically we can stabilize the temperature. Stabilizing the Keeling Curve will be really tough. Stabilizing global temperature will be a "bit" harder. Use Table 1 to monitor our progress.

Making this personal

A decrease from 2.5 to 2.4 is a 4% decrease the first year. But because in 2021 population is increasing about 1%/yr, this means that each person on Earth, on average, must decrease their carbon emissions by 5%/yr to compensate for the carbon emissions of the newborns. By some estimates, 25% of the world need assistance to rise up out of poverty. Not only do they lack the reserves to cut their carbon emissions, but they deserve the chance to rise to a higher standard of living. If we reduce our emissions sufficiently to cover their lack of ability to reduce emissions, and then reduce our emissions further so that they can rise up out of poverty, those in developed countries need to decrease their emissions about 8% the first year, and the same amount year after year after year.

What does this mean? If you drive a car 15,000 miles/yr, that means driving 1200 miles less the first year, 1200 miles less the second year, etc. At some point you need to buy a car with much higher mileage. You need to buy 8% fewer clothes the first year, and then 8% fewer the next year, etc. Or buy clothes with a lower carbon footprint and wear them longer. Eat 8% less each year, or eat food with a lower carbon footprint. Heat and cool your house 8% less the first year, or insulate your house better and install a more efficient heating/cooling system. Because there is a limit to how much we can reduce our emissions, at some point we accept that we will continue emitting some carbon and build systems to remove carbon from the atmosphere to compensate for our baseline emissions. These are collectively called Negative Emissions Technologies (NET).

Where does this take us?

If we get the entire world on board with this carbon-reduction plan so that we successfully implement the carbon-emission-reduction schedule shown in Table 1, this represents a total increase of 35 ppm CO2 relative to the 2021 level of 415. That means that by 2050 we will have 450 ppm CO2 in the atmosphere, enough to take us to 2°C warming … even with a revolutionary decrease to Net-Zero by 2050.

What does this mean? We are at the gates of Hell. Anything less than a revolutionary approach to decarbonization and we will enter a place we've only dreamed of. Is this the future you want for your children and grandchildren?

The future is either about revolutionary changes to how we run society, or adaptation to revolutionary climatic changes. Time to choose. Time to act!

Footnotes

1. Referring to a talk by the same name given by Prof. Kevin Anderson in 2015.

2. The data point for 2020 is a 3-year average of the raw data from 2019, 2020, and 2021.

3. For those concerned about extrapolating a quadratic equation, the R2 = 0.9998 for the trend line fit to the 10-yr averaged data from 1970 to 2005.

4. Some use a definition of Net-Zero to mean that our Net GHG emissions reach 0, a goal that is virtually impossible to verify. For this post I define Net-Zero to mean that the net, annual accumulation rate of CO2 in the atmosphere reaches 0, a goal that is easily verified. Read here for more details about the distinction between these two definitions of Net-Zero.

5. Whereas some project a global population of 9 billion people by 2050 and others 10 billion, I’ve used a value between these two of 9.5 billion people.

Arguments

Arguments

Well, that is one of the more depressing posts that I've seen: looking at those charts and numbers can be used to convincingly argue quite a different conclusion: it's too late. According to World Energy Consumption patterns I've looked at (and there are no doubt more current analyses), there was a huge jump in energy consumption in the 1970s, with a 65% increase in 10 years, dropping off to a mere 15% energy growth per capita by 2000, bouncing back to 25% increase from the previous decade by 2010, and yet there was barely any change in the growth rate of CO2 emissions during those times. I presume that this is due to population growth that ate up the increases in efficiencies, so that even modest increases in global per capita energy consumption (1965: ~48Gj/person, 2010: ~74) resulted in almost no change in the emissions trajectory.

While it is easy to turn a line dramatically down to zero from this incessant, steady rise in consumption, it is very hard to envision the circumstances it would require to actually turn that arrow downward in such a dramatic fashion. Compared to the 1970s, so much has changed, and yet the slope of the curve marches on and up. The word Revolution seems to be a gross understatement. Collapse might turn the curve in the manner you draw it: either through some unparalleled catastrophe, or if the trends continue, climate-induced collapse. Please tell me I'm wrong and why.

wilddouglascounty, agree, that is a depressing post. My point in writing it is that if, if we are to achieve Net-Zero, I think people should realize what is needed to make it happen. I would rather shock them now then wait until they're shocked later.

I wrote a long, not very readable post about modeling I did (read here). You can make a strong case, using the IPAT equation, that for the last 50 years, improvements in the carbon footprint of producing goods and services have been offset by rising consumption. That leaves the annual increase in global population as the main driver of increasing atmospheric CO2 accumulation rates, which has been steady for about 50 years at 80,000,000 new carbon emitters/year.

Figure 2 in this post was a shocker to me when I created it, showing that for about 100 years, carbon accumulation rates in the atmosphere appearto be due entirely to population, independent of the modernity of civilization.

It's a tough nut to crack. And sorry, I won't tell you you're wrong about what it might take to turn the curve downward.

Evan,

I may provide a more comprehensive response, but I have to think about it a little more.

My main point is that the "population problem" is the way that less fortunate people can be easily tempted to aspire to develop to live like the people who are identified as the most successful, highest status people.

Parts of my comments to Peter Cook on your recent item "The problem of growth in a finite world" are related to this 'population' topic.

My developed perspective and understanding is that the people recognised as the most successful, highest status people, need to be people who are striving to live the least harmful most helpful ways possible:

I agree. Understanding that that is the required correction of what has developed is reason to question how quickly the harm being done to the future of humanity will be limited.

But I believe humanity has to have a future. Humanity inevitably has to collectively and collaboratively grow the portion of the population that understands the need for the highest status people to be constantly striving to provide the best examples of Sustainable Helpful Living for all others to aspire to be better than.

As that portion of the population grows it will develop increased ability to limit the harm done by the portion of the population that has developed a liking for resisting learning to be less harmful and more helpful.

Probably the most important understanding is that the "Great Recession" and "Covid Pandemic Lockdown" were not "temporary emission pauses".

Though the rate of harmful impact in each case was reduced by a measurable amount, the harmful impacts were not "Temporarily Zero".

This understanding highlights that things will continue to be made worse until "global net-zero living (highest status people being net-negative impact by zero-carbon living and reducing impacts to off-set the impacts of lower status people who have more excuse for being harmful)" is achieved by correction of all harmfully incorrect development that has occurred.

The current harmfully incorrect developed ways of living, esepcially by the higher status people, make things worse as they are continued. Hope for a 'solution to be developed' misleadingly makes things worse.

What is needed now is the reduction of energy use and other harmful consumption that has been harmfully over-developed by the supposedly more advanced and superior people. Using less energy makes the end of harmful energy use come sooner with less total harm done. Once net-zero is achieved it may be possible to sustainably improve things with more energy use.

Indeed, 25% of the world population needs assistance to rise up out of poverty, and they should be helped to live basic decent lives. It is also important to acknowledge that those helped out of poverty, and everyone else, has the right to strive to live more like the higher status people, even if that is more harmful and less sustainable. Higher status people do not have the right to be more harmful. They have the responsibility to set the best examples.

The solution is dramatic reductions of harmful developed ways of living by the highest consuming and impacting portion of the population. The highest status people need to all be leading the transition to net-zero living, meaning they live net-zero far earlier than others and they penalize any of their peers who are not doing that.

And, to be more sustainable, it would be best to have the development assistance that is provided for the less fortunate help them jump directly to net-zero basic decent living. That would be less harmful, but require more assistance, than the approach China is pushing. China is building coal burners for developing nations with the 'intent to rapidly replace them with net-zero systems'. Best intentions often get delayed, or worse, do not materialize.

Note that the UN is now pursuing a global agreement to limit plastic use. That is a sign of advancement, as long as it rapidly meaningfully materializes.

Very thought provoking article Evan.

Your idea seems to be that with the increasing per capita use of energy over the last 150 years, due to the adoption of car ownership, electric heaters, and multiple appliances, etc,etc, we should have actually seen a much bigger acceleration in the keeling curve. I'm guessing that the reason we haven't might be because of higher energy efficiency in using fossil fuels, such that we are using less fossil fuels per capita to get the same results for example with more fuel efficient cars, power generation, and heating devices. So it may not necessarily be just population per se driving the keeling curve shape.

That said, obviously population is a big factor in the keeling curve. I've always thought overpopulation is one of our biggest environmental problems, followed closely by per capita consumption levels (obviously particularly with high income groups), and we have now learned in recent decades that fossil fuels are a problem. We know the solutions to all this, but its a bit like trying to turn around the Titanic.

nigelj@6 Thanks for your comments.

The IPAT equation relates Impact (in this case, the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere) to Population, Affluence, and Technology, which is really a measure of the carbon footprint of producing our goods and services. Expressing affluence as Global GDP per person, and expressing the carbon footprint of producing goods and services as the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere per unit GDP, you can make the case using the IPAT equation that there has been a steady decrease of the carbon footprint per unit GDP over the last 50 years, which has been offset by rising affluence, leaving population as the main driver of the accumulation of CO2 in the atmosphere (read here if you have a few hours to kill). The upward acceleration of the Keeling Curve therefore appears to be driven by population increase. If global population stopped increasing, the Keeling Curve would increase as a straight line. But population growth causes the Keeling Curve to accelerate upwards.

And yes, it is surprising that Figure 2 suggests this relationship goes back to at least the early 1900's. Population is one of the main drivers of the Keeling Curve, and while we are deployiing renewable energy systems to try to stabilize the Keeling Curve, population growth will be working against us.

It's a tough nut to crack. I'm not trying to depress people, but to get people ready for what will be required to tackle the climate crisis.

The author wrote "Monitoring our approach to Net-Zero is conceptually easy. Just measure the CO2 concentration each year and see if it stops increasing".

I disagree. Net-Zero means humanity's emissions are in balance with what humanity removes from the atmosphere themselves. If that were the case, then the biosphere should be removing additional CO2 from the atmosphere so that the concentration would actually drop.

The author wrote: "If the rollout of renewables in the 2020’s is to have any chance of impressing the Keeling Curve, it needs your full support: in addition to replacing fossil fuels with renewable energy, we must consume less."

I used to believe this too. However, the En-ROADS climate and world economy model shows that you can in principle achieve warming under 2 degrees C with economic growth on the side. Here is the link to En-ROADS

https://en-roads.climateinteractive.org/scenario.html?v=22.3.0

En-ROADS does not allow for degrowth. It would have been interesting if they had included it in their model. But it does show that it is still possible to have net economic growth on the global scale while meeting the conditions of the Paris Agreement. You have to play with the program to get a solution by pulling policy levers.

What would cause the "higher status people", the "affluent" to roll back their emissions so the less fortunate can execute the right to obtain a decent living standard? Since we already know that for every right asserted by a human, there must be a corresponding obligation by some other human, what mechanism would you introduce to persuade or force the obligated to satiate the obliged? What would you do if the obligated resisted shouldering the obligation? We know that the majority of the global population has missed the benefits of material wealth while the last hundred years has showered a comparatively opulent batch of goods and other stuff on the minority. What tool of social engineering would bring to heel the "better offs" to provide the space in their emissions footprint so as to provide this "right" of which you speak?

Swampfoxh @9 , the social engineering tool you speak of is Carbon Tax with Dividend ~ which has a good track record in its very brief/limited career. Of course, it needs to start small & go slow, to get widespread political acceptance. Have you other tools in mind?

Plincoln24 @8 ,

Our-World-in-Data states a world total energy consumption of just under 200,000 TeraWatt-hours annually. A lot. And of this, 84% is fossil fuel [oil 33 ; coal 27 ; gas 24% ] plus 5% solar/wind/other [not including nuclear & hydro ]. These figures not including land-clearing and cement production.

Obviously it will be a long & slow uphhill climb to get to all 200,000 TWh coming from carbon-free sources. Presumably this figure will go higher even without much population growth.

Some sort of "renewable" liquid hydrocarbon fuel will need production in large quantities in the second half of this current Century.

Plincoln24 , perhaps if you have time, you could discuss what you (and others) mean by the term economic growth ~ a term which is often used in a vague undefined way.

plincoln24@8 Regarding what we mean by Net Zero, I wrote a separate article (read here) where I describe the difference between Net-Zero Emissions (what you refer to) and Net-Zero Accumulation (what I refer to in this article). By definition, we must achieve Net-Zero Accumulation before achieving Net-Zero Emissions.

What I show in Fig. 2 is Net-Zero Accumulation, which means that atmospheric CO2 accumulation hits 0. As wilddouglascounty@1 pointed out, this seems only achievable through "collapse". To achieve Net-Zero Emissions will be even harder.

Without splitting hairs, what I am trying to show is the challenges that lay ahead. I understand the definitions to which you're referring, but people cannot, on their own, monitor our progress to Net-Zero Emissions. They can monitor our approach to Net-Zero Accumulation by following Table 1. I am trying to help people learn how to monitor our progress.

Yes, I've read about how we can maintain "robust economic growth" in the IEA report. But that is a study, assuming the entire world follows their roadmap, and that everything works out as planned with the technology (NET systems at scale are still a plan, not reality). Reality is that absolutely nothing we've done, to date, has caused the Keeling Curve to deviate from its upward acceleration. If we keep telling people that we can keep increasing our consumption (i.e., growth) while stabilizing the Keeling Curve, we may miss this final opportunity to deal with climate crisis.

Where I disagree with you is the use of the words, "in principle" and your reference to "pulling policy levers" I don't necessarily disagree with the models, scientifically and conceptually. I disagree that you can implement the models on 8 billion people spread across almost 200 countries.

And by the time we are supposed to achieve Net Zero, there will likely be 9-9.5 billion people. Dealing with that kind of population growth is a huge headwind, that likely can only be offset by encouraging people to consume less.

Eclectic

I had in mind: The collision between emissions producing a somewhat higher than 3.0C, the terrestrial damage already, and yet to be done, and the size of the global population will winnow itself out in a general catastrophe similar in scope to the very early End Triassic or perhaps the early End Paleocene extinction events. The population is likely to fall back to around 500 million which removes both the GHG emissions problem and the terrestrial damage events fostered by human activity over these past 200 years.

Evan,

In my comment @13 on your earlier post “The problem of growth in a finite world” I point out that the "Emissions = Population x GDP/capita x Energy/GDP x Emissions/Energy” can make it difficult to see the important need for superiority and advancement to be recognized as "reduced energy use per person" and "reduced harm done by the energy that is used" (because any use of technologically produced energy has the potential to produce harmful results).

I also point out that, since everybody’s actions add up, that presentation is a potentially misleading sub-set of the overall issue of the clearer simpler presentation that: "Total Harmful Impacts = The sum of the harmful impacts attributable to each person".

That leads to understanding that there will be a diversity of degrees and types of harm that would be hidden by averaging the impacts of a group of people.

The following series of recent articles in The Guardian point out how important it is to recognize the different levels of impact, and how harmful it is for the people perceived to be superior or more advanced to be more harmful than the average rather than leading the pursuit of sustainable development which requires leadership towards reduction of harmful ways of obtaining personal benefit and enjoyment.

‘Carbon footprint gap’ between rich and poor expanding, study finds (Feb 4, 2022)

This article identifies the key point that 'from 2010 to 2015' the wealthiest have become more harmful.

“In 2010, the most affluent 10% of households emitted 34% of global CO2, while the 50% of the global population in lower income brackets accounted for just 15%. By 2015, the richest 10% were responsible for 49% of emissions against 7% produced by the poorest half of the world’s population.”

That means that if everyone alive in 2010 developed to live as harmfully as the top 10% did just under 30% of the 2010 global population (6.922 billion) = 2 billion, would produce the total global impacts of 2010.

If everyone alive in 2015 developed to live as harmfully as the top 10% did just over 20% of the 2015 global population (7.348 billion) = 1.5 billion, would produce the total global impacts of 2015.

The article also points out that in 2015 the top 1% contributed 15.3% of global CO2 emissions (and the top 0.1% caused 4.5%). If everybody alive in 2015 developed to live as harmfully as the top 1% did then just over 6.5% of the 2015 global population, 0.065 of 7.348 billion = 480 million people would produce the total global impacts of 2015. And it would be worse if people developed to live like the top 0.1%. That spoils swampfoxh’s hope that a 500 million global population “removes both the GHG emissions problem and the terrestrial damage events fostered by human activity”.

Also note that global emissions in 2010 were 41.8 Gt CO2 equivalent. The 2015 total was 44.4 Gt. So, to maintain the global total emissions impact at 2010 levels, the number of people living like the top 10% did in 2015 would be 1.4 billion.

And those evaluations are to maintain the 2010 and 2015 levels of accumulating harm done.

Since everyone has the right to aspire to live like the ones who are perceived to be the highest status, and it is foolish to pretend that that is not the case, the problem can be seen to be the example set by the way that the top 10% live.

The way that the top 10% lived in 2010 was already unsustainable. And the top 10% were even worse in 2015. If that “advancement trajectory” is not reversed there will be no sustainable future for humanity.

This is indeed a very challenging understanding. It leads to recognizing that the higher energy consuming 5G communication technology is a harmful leap further away from sustainable living.

The richest 10% produce about half of greenhouse gas emissions. They should pay to fix the climate (Dec 7, 2021)

Includes: “Let’s first look at the facts: 10% of the world’s population are responsible for about half of all greenhouse gas emissions, while the bottom half of the world contributes just 12% of all emissions. This is not simply a rich versus poor countries divide: there are huge emitters in poor countries, and low emitters in rich countries.”

‘Luxury carbon consumption’ of top 1% threatens 1.5C global heating limit (Nov 5, 2021)

Includes: “The carbon dioxide emissions of the richest 1% of humanity are on track to be 30 times greater than what is compatible with keeping global heating below 1.5C, new research warns, as scientists urge governments to “constrain luxury carbon consumption” of private jets, megayachts and space travel.”

A version of Carbon Fee and Rebate would help solve the problem. But it would need to be based on understanding the need for ‘progressive penalties’ for harmful ways of living. The richer a person is the more they should be penalized per-unit of harmful impact. A crude way to do that is a Carbon Fee and Rebate program that only rebates the total collected to the middle and lower income portion of the population. A more refined method would be progressive rebates of the collected fees that are higher for lower income people. That method would avoid concerns about ‘costing the middle and lower income people’. It would be easy to show that the middle and lower income people actually benefit from the program. A higher Carbon Fee and resulting higher total collected for Refund would be better for them. There would be no need to slowly increase the carbon fee. It could statrt at $200 per tonne. Admittedly, the irresponsible among the middle and lower income portion of the population may only break even. And the grossly irresponsible would lose a little. But those who resist learning to change how they live to be less harmful have to face a consequence. And the richer they are the less excuse they have for being more harmfully irresponsible.

OPOF@13, points noted. But at the same time, this is why Fig. 2 is so astounding. Something is working itself out in the system to produce CO2 accumulation rates that simply scale with population. I understand what you're saying, but it's not clear to me how much it matters. Even if you neglect the top 10% of emitters, you are still left with a completely unsustainable problem.

And of course 100 years ago there was also a distribution of emitters: rich, middle class, those aspiring to rise to the middle class. What Fig. 2 is suggesting is that it may work itself out in the averages.

Evan @7. Thank's. Your explanation is convincing. The facts are sometimes depressing. People just have to deal with that.

To the above I'll add that yesterday without bothering to consult the general population the US congress ruled out an embargo on Russian fossil fuel imports to the United States, because "higher gas prices."

This helps to set our expectations with regard to dealing with climate change.

Evan @14

Something seems wrong in your analysis. The population versus atmospheric emissions growth trend is dependent on a population using fossil fuels. So if people reduce their consumption of fossil fuels ( and all other things stay equal) emissions must drop, and atmospheric CO2 reduces eventually. Since rich people consume more fossil fuels they are contributing to more of the problem. Isn't all that simple logic?

Although I'm rather doubtful that rich people will cut their emissions very much by simply reducing their levels of consumption ( eg turning down the heater to low, or giving away all their assets). They will buy things like electric cars and insulate their houses. So the biggest lever we have to mitigate the problem is still probably renewable energy and negative emissions technology, as per your conclusions elsewhere.

Evan,

Part of the reason for the observed result could be that the intensity of emissions per person may have been very high when inefficient coal burning was driving industrial advancement.

But, the potentially revolutionary understanding is that this is the first time in history that we are seeing undeniable evidence of the need to shift away from the historic human development behaviour of competition for perceptions of superiority relative to others, with everyone striving to live more like the people who are seen to be higher-status based on measures of material consumption or material possession.

The higher status people being higher harm producing per person is likely the root of the problem.

Evan,

Deforestation and other land use changes may also have been much higher 'per capita' in those earlier years of development.

Eclectic at 10:

The problem with hydrocarbons from renewable energy is that hydrocarbons are a completely wasteful use of energy. That generally means that making hdrocarbons from renewable energy will be expensive. Connelly et al 2020 (summarized at SkS here) (free similar paper) describe the steps to have a 100% renewble all energy economy. They use methane for storage and for powering those parts of the economy that cannot be converted to electricity. Generating the power to make the hydrocarbons needed is one of the most expensive parts of converting the entire economy to renewable energy. Hydrocarbons are very cheap to store (as much as 1,000 times cheaper than batteries) which offsets their high cost.

There are two ways to get renewable hydrofuels from renewable electricity. You can capture CO2 from the air (this uses energy). Than you use electricity to get hydrogen from water. Then you convert the hydrogen and CO2 into hydrocarbons. You lose about 30% or more of the energy during this step. Burning the hydrocarbons you only get back about 20-40% of the energy stored in the hydrocarbons. Net you only get about 5-25 joules of useful energy from every 100 joules of input electricity (common uses like cars are nearer to 5%). If you put the energy into car batteries and than run the car you get about 90 useful joules of energy from inputting 100 joules of energy. Converting everything possible to electricity saves so much energy that hydrocarbons are ony economic for purposes that cannot be converted into electric power like marine transport (some people propose using ammonia to power marine transport. Ammonia has the same issues as hydrocarbons.)

You can also get hydrocarbons by electrolysis of carbon containing materials like forest waste. That takes less energy than converting CO2 into hydrocarbons. The supply of plant waste is limited and it is still much more expensive than electricity so using electricity instead of hydrocarbons is more economic.

Fuels like biodiesel made from plant oils use too much land that is needed to raise food, although every little bit helps.

nigelj@17, yes, "if people reduce their consumption of fossil fuels" then wonderful things might happen. But so far, fossil fuel use is increasing each year. Figure 2 is based on a sufficiently long time period to pretty solidly suggest that when averaged out, population is a key driver. That is all I'm really trying to say. What we are trying to do is to move off of that fundamental curve. There is lots of talk about how easily we'll be able to do it, but so far we are still solidly on it.

OPOF, agree with your assessments of what might have been driving early GHG emissions. However you slice it, it is remarkable that we've been on this straight line for about 100 years.

Michael Sweet @20 : Quite right, the hydrocarbons are a wicked problem. The FF hydrocarbons have their 84% of total energy because they are cheap and very convenient (plus legacy low-technology).

As you say, crops grown specifically for biodiesel/gasoline are unjustifiable.

Yet there may be room for biological waste material to be fermented and/or hi-tech enzymatically converted into suitable fuels. I haven't followed the latest developments ~ last I heard, some pilot plants could produce "oil" at $200 per barrel. Even allowing for initial enthusiastic hype . . . how practical & economic would it be to scale up such processes? OTOH, hi-tech CO2 capture & conversion may have a place in the middling future, when the world is really awash in superfluous solar (PV) energy. We can hope !

As you know, the liquid hydrocarbon fuels are so very useful in many small areas, where their compactness, light weight, easy storage, and overall convenience give them a big tick of approval. And even in 50 years' time, the hydrocarbons will still be on target for "large niche" areas of aircraft and shipping and heavy machinery.

The (renewable) hydrocarbons will become a luxury fuel at a luxury price. At twice or more the current price, they will still be affordable when viewed against the overall costs of ships, jetplanes, etcetera.

The short-term political problem remains . . . e.g. my brother-in-law almost faints when gasoline goes up 10 cents. Quite irrational : but it's a widespread emotional response . . . and which affects votes.

Eclectic:

I think we basicly agree on the generalities.

The key for the next ten years is to build out wind and solar energy as rapidly as possible. Convert all cars and most other transportation to battery electric. 80% of electricity can be generated using wind and solar with fossil natural gas as storage using existing gas generators. Electric storage can be built as needed. Convert all heating and cooling to heat pumps (cooling is already mostly done with heat pumps). Connelly et al 2020 suggest that all storage can eventualy be electrofuels made for heavy industry and generating peak power when renewable sources are low.

It will be interesting to see if Europe (and the USA) decide to build out more renewable energy to get out from their dependance on Russian gas and oil.

Eclectic:

ps: My brother installed solar panels on his roof and bought an electric car. He doesn't care what the price of gas is!!

Michael Sweet @ 24/25 :

Care to swap brothers-in-law ?

Electrofuels ~ I will have to remember that term. It seems the best bet for large scale storage, once the marginal price gets low.

The goal of Net Zero carbon emissions by 2050 is impossible, as it violates the most fundamental laws of the universe. For example, Carbon the fourth most abundant element in the universe by mass after hydrogen, helium, and oxygen. Carbon's abundance, its unique diversity of organic compounds, and its unusual ability to form polymers at the temperatures commonly encountered on Earth enables this element to serve as a common element of all known life. It is the second most abundant element in the human body by mass (about 18.5%) after oxygen.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carbon

The goal of Net Zero Carbon Emissions by 2050 is as impossible, if not more so, than was the Marxist goal to abolish private property.

I write this not because I am a so-called "Denier" that there is Climate Change, and nor am I opposed to action on Climate Change. But I do believe it is extremely important to be realistic about what can be achieved, in order to develop achievable public policies.

For example, In 2021 a Lazard study of unsubsidized electricity said that the median cost of fully deprecated existing coal power was $42/MWh, nuclear $29/MWh and gas $24/MWh. The study estimated offshore wind at around $83/MWh and utility-scale solar power was around $36/MWh.

The International Energy Agency said in 2021 that under its "Net Zero by 2050" scenario solar power would contribute about 20% of worldwide energy consumption, and solar would be the world's largest source of electricity.

However, both solar and wind are variable (VRE)/intermittent (IRES) energy sources, and therefore are limited in the extent to which they can replace non-renewables due to their fluctuating nature: i.e. at night time solar must be replaced by other power sources; and likewise, wind must be replaced during low wind periods.

Nuclear $29/MWh has almost zero carbon emissions, and Australia where I am from has an estimated 40% of the world's uranium. However, there is almost zero support in Australia for switching to nuclear, in large part because countries with nuclear power like the U.S., U.K. and France don't want to provide us in Australia with the nuclear technology required, as they are against the spread of nuclear technology.

If Australia was to invest in sufficient nuclear power to provide not only our present electricity needs, but also enough to power electric cars as well, then it would require a huge amount of money to replace our coal power stations with nuclear power stations, and take about 15 to 20 years to build. But that is the cheapest possible way for us to reduce our carbon emissions, and it would only reduce our carbon emissions by about 50%. It is therefore the wisest thing we can do as a country and gives us the best chance of reducing our emissions.

Even by doing the above switch to nuclear, we would certainly not get anywhere near Zero Carbon Emissions by 2050, because to reiterate that goal is impossible.

Reuben Fraser:

Here is a link to the 2021 Lazard study.

I note that the cost of unsubsidized onshore wind is $25-50. The low end is cheaper than all existing coal and nuclear and a portion of combined gas genertaion that has no mortgage. You take the cost of existing nuclear power with no mortgage and compare it to new renewables with a mortgage. If they built out nuclear in Australia they would have to pay the mortgage and nuclear would be the most expensive energy. I suggest you learn how to read your references. I note that the price of gas has skyrocketed since the Lazard report was written. Today renewable energy would be chepaer than gas generators with no mortgage. The price of renewable energy does not change with the political winds like fossil fuels do.

New build renewable energy is much cheaper than all other new build electricity sources. We see that world wide few fossil or nuclear power plants are being started. The cheapest power is produced from renewable energy.

It is possible for renewable energy to provide all the needed energy for the world, you have just not informed yourself. Connelly et al 2020 describe how to build an all renewable energy system for Europe. Many other all renewable energy systems have been proposed.

The abundance of carbon in the universe does not relate to the release of CO2 into the atmosphere.

The IAEA increases their projections of how much renewable energy will be built in the future every year. They overestimate the amount of fossil energy that will be built.

I'm curious as to why this discussion revolved, largely, around GGEs from fossil fuels. Industrial Animal Agriculture's direct carbon footprint comes in around 31%. Its indirect footprint is variously estimated between 20% and higher numbers. On top of its footprint, we have to add in the environment damages which include deforestation, desertification, eutrophication and acidification of oceans, habitat loss, wild animal extinction, outsized fresh water use, land use conversions, human disease and disorders, especially cardiovascular...while consuming 85% of global crop tonnage, occupying 45% of arable land, while contributing only 1.5% to the gross global value of goods and services. Should not Industrial Animal Agriculture be targeted for elimination in the same manner as fossil fuels?

@Evan

This is a response to comment number 11 which you posted in response to my comments about En-ROADS.

You wrote "Without splitting hairs, what I am trying to show is the challenges that lay ahead. I understand the definitions to which you're referring, but people cannot, on their own, monitor our progress to Net-Zero Emissions. They can monitor our approach to Net-Zero Accumulation by following Table 1. I am trying to help people learn how to monitor our progress."

I think you are right that simply looking at Table 1.1 is better for members of the public.

I am not familiar with the IEA report. I don't think that pushing for more consumption is the right way to solve our problem. I wish En-ROADS included a lever that has policy that creates degrowth. It doesn't, and I think that the lack of its inclusion is a sign of bias in the producers of the En-ROADS program. I think it would be a lot easier to achieve our climate obligations if we allowed for degrowth in the global economy. I in fact advocate for integrating degrowth into our climate solutions.

You write "Yes, I've read about how we can maintain "robust economic growth" in the IEA report. But that is a study, assuming the entire world follows their roadmap, and that everything works out as planned with the technology (NET systems at scale are still a plan, not reality). Reality is that absolutely nothing we've done, to date, has caused the Keeling Curve to deviate from its upward acceleration. If we keep telling people that we can keep increasing our consumption (i.e., growth) while stabilizing the Keeling Curve, we may miss this final opportunity to deal with climate crisis.

Where I disagree with you is the use of the words, "in principle" and your reference to "pulling policy levers" I don't necessarily disagree with the models, scientifically and conceptually. I disagree that you can implement the models on 8 billion people spread across almost 200 countries."

To this I say what we should be telling people is what we would say if we were being as honest as possible. I agree with you that we probably wont solve the climate crisis if we fail to implement degrowth. We should do that. But the reason we need to do it is not because it is physically impossible to have economic growth and solve the climate crisis simultaneously. The reason we should implement degrowth is because growth does not equate with well being and including degrowth in the plan increases the probability of success dramatically.

I have met a lot of resistance trying to convince politicians that degrowth should be part of their political platform. I have had more success trying to convince them that a high price on carbon should be. I get the since that it is counterproductive for me to try to sell the degrowth concept at the local level, the national level or even at the EU level. It seems like something that needs to be a global agreement, like a global price on carbon would be. I wrote to James Hansen with regards to my concerns about economic growth needing to be addressed and he wrote back that the size of the global economy could be restrained by placing a fee on energy consumption that rises with time as you approach how large you want the global economy to be and the fees could be paid back out to the public in the form of a dividend (much like the carbon fee in dividend). I like this idea, and if we are going to take such an approach, it makes most sense to introduce a fee on the energy consumption which is the worst (emissions) by introducing Carbon Fee and Dividend, and then when the public is ready for it, sell them on protecting nature from economic growth by taking the existing Carbon Fee and Dividend program and rolling out a generalized fee on all energy sources. In my mind we need to have success with selling the public on a global price on carbon on the order of hundreds of dollars per ton CO2 before moving on to economic growth. I am not sure why you think that the policies cannot be implemented on the 8 billion people of the globle. If you mean it is because it is politically impossible (politicians would never agree on it), then you might be right). I don't otherwise understand why you would say that the policies in En-ROADS cannot be implemented on 8 billion people. In some cases it is clear you could. One policy is a global ban on new coal infrastructure from a year of your choice such as 2025. Another policy is a precentage increase in electrication of transportation per year. This latter policy could be implemnted at different rates for different nations (depending on their situation) where the desired global average is maintained. Anyhow, I view James Hansen's suggestion of applying a fee to energy in general to be a powerful tool which would take care of most of kinks associated with getting a global agreement on limiting economic growth. There would be other details naturally. But that method doesn't make sense without placing a fees on the forms of energy which are worse for the environment first. You are free to respond.

@Evan,

I don't see that I can edit my post.

I wrote " I get the since that it is counterproductive for me to try to sell the degrowth concept at the local level, the national level or even at the EU level".

Since should have been sense. Sorry for the error.

plincoln24, thanks for your detailed responses. I also like the idea of a carbon tax as you described. I could respond to your detailed discussion, but I am basically in agreement with all that you say.

One of the most natural ways to reduce GHG emissions is to reduce consumption. It is better not to consume than to try to consume using low-carbon methods. There is another angle where this becomes important. In an upcoming post I will show that the rise of renewable energy, to date, has had no effect on the upward acceleration of the Keeling Curve. The reason is simple. Renewable energy on its own does nothing to reduce GHG emissions. Only switching from fossil-fuel energy to renewable energy will reduce emissions. Apparently renewables are growing alongside fossil fuels and not replacing them. Because renewable energy is currently supplementing fossil fuels, and have not replaced them in any significant measure (speaking from a global, total integration perspective), people can hasten the transition from fossil fuels to renewables by consuming less, because presumably any decreased consumption will directly reduce fossil-fuel usage without changing the level of renewables, simply because renewables are currently only supplementing fossil-fuel energy.

I hope we agree that reduced consumption must be part of the solution if we are to achieve the ambitious goals of stabilizing the climate, whenever that occurs, and at whatever level that occurs.

@ Evan: You wrote "I hope we agree that reduced consumption must be part of the solution if we are to achieve the ambitious goals of stabilizing the climate, whenever that occurs, and at whatever level that occurs." We agree.

I am interested to see that upcoming post where you write about the non impacts of the renewable energy on the keeling curve.

Evan, plincoln24

You have considered reduced consuption as a policy that might positively reduce the GGE problem. Thus, might you support the elimination of Industrial Animal Agriculture (IAA)? There is already a suitable, adequate and immediaty available, alternate, food supply that can replace meat. Plants. Livestock enterprises contribute only 1.5% to the Global Value of Goods and Services (Gross Global Product). 1.5% is virtully negligible, and easily replaced by the growing of plant foods for humans. IAA emits at least 31% of total global GHG emissions while having an outsized deleterious effect on the environment. There are only about a million animal farmers in the U.S. They are, numbers-wise, an unimportant interest group and are only a small handful of voters. Current livestock farmers could be persuaded to abandon the livestock business through a buyout program where they agree to abandon this industry in favor of a "Eco-Ranger" (government) subsidy that promotes land re-conversion to non-livestock uses, the regeneration of wild animal species, returning former domestic farm animal acreage into forest and riparian zones, and so forth. Any interest in this topic being assessed alongside Fossil Fuels?

I should point out that we see very little traffic in scientific literature on the subject of Animal Ariculture's impact on the environment. I would have thought that knocking off 30% to 50%, perhaps more, of the global greehouse gas emissions currently being pumped into the atmosphere would draw considerable attention. Please offer me your suspicions on why the narrative about livestock seems not to arrive at the surface of the discourse on Scep/Sci?

[BL] You have asserted numbers similar to this more than once recently.When I look at the most recent IPCC report, I see discussions of methane, N2O, CO2 that include agricultural inputs, so I don't know where you get the "little traffic" argument from.

Perhaps you could start by posting some references/sources for the numbers you are throwing out.

Evan,

Here are some thoughts that I believe are fairly closely aligned with the points made by plincoln24, and builds on points presented in my earlier comments.

It is likely that what is seen in Figure 2 is the result of the limited success of efforts to identify and increase awareness of harmful developments. And that leads to the awareness and understanding that significant correction of what has been developed is required to limit the climate change harm so that sustainable improvements can be developed. It also leads to understanding that harmful popular and profitable developments can be expected to powerfully resist being corrected and limited.

I prefer to say something like ‘correction of harmful development’. Degrowth is too generic. I understand that undoing harmful developments at the pace required to limit harm done to future generations could result in reductions of measures used to track economic progress like GDP. But that indicates that the measure of economic progress failed to properly account for harm done because they are ‘externalities to the money math that are hard to precisely monetize’. They would be negatives if they were monetized.

I have been looking for a specific reference, but have not found ‘the one document’. My perspective and understanding is based on many evidence-based presentations of understanding. The 2020 Human Development Report comes to mind as a comprehensive presentation that supports a lot, but maybe not all, of my current understanding.

I will start with a positive comment.

When less harmful ways of doing things are perceived to be more beneficial or desirable the Marketplaces, including the marketplace of public opinion (increased awareness and popularity), can be helpful. Collective and collaborative societies are also marketplaces. But the majority of global marketplaces, including dictatorships and non-capitalist societies, are more competitive than collaborative or cooperative marketplaces.

There have been instances when the competitive marketplaces developed less harmful replacements for more harmful developments without formal Government Intervention. The marketplace can self-govern by collectively and collaboratively identifying and correcting harmful developments. But the fact that Government Intervention has been required to limit harm done by so many developments indicates that there are Harmful Errors in the major developed Systems, especially as pursuits of profit grow beyond regional family businesses.

Significant helpful Government Intervention in the marketplace competitions for perceptions of superiority have limited the increase of CO2 in the atmosphere. Those interventions, like imposing requirements for improved fuel efficiency, have kept the harm done by human developments lower than would otherwise have developed. But the harm continues to add up because there is powerful resistance to those helpful interventions.

Some people harmfully resist, rather than helpfully support, helpful government intervention that would correct or limit harmful developments. The resistance can be more powerful if the intervention would correct harmful popular beliefs (misunderstandings) and/or restrict or stop harmful activities that are beneficial (profitable) for some people to the detriment of the ability to others to live at least a basic decent life. That resistance has kept the CO2 levels increasing rather than levelling off. And part of that resistance has been the fight against actions like Carbon Fee and Rebate (best if rebated only to the middle income and below).

Misleading marketing develops and sustains harmful lack of awareness and harmful misunderstanding. Limiting (ideally ending) harmful misunderstandings and related actions that harm future generations and harm less fortunate people today is a massive challenge. It requires:

A particularly challenging requirement is for all leadership competitors to lead the efforts to not be harmfully misleading. Giving up the potential power and competetive advantage that can be obtained by developing and sustaining harmful misunderstandings is a challenge. It requires many higher status people to accept some loss of unjustified perceptions of status. And that is where misleading marketing is really harmful. Marketing science has developed tremendous understanding about how easily people can be tempted to harmfully misunderstand things when they perceive that they are personally going to benefit or lose. The potential harmfulness of their misunderstanding and related actions will easily become less of a concern for them than their ‘gut-reaction - instinctive’ perception of personal benefit or loss.

The focus of SkS on raising awareness of harmful misunderstandings and misleading marketing regarding climate change impacts is very helpful. But it is hard work because many people are powerfully motivated to misunderstand climate science because of the identified loses of perceptions of personal benefit that are now needed, more than were needed before, to limit the harm done to 1.5C. The push to continue developing in the harmful direction through the past 30 years, especially by the higher status supposed leaders has made it even harder to achieve that fair limit of harm done to the future of humanity.

Because of the lack of reduction of harm done by the richest through the past 30 years, and the continued resistance to correction by many of them today, an increasingly dramatic loss of status is required, as indicated in Figure 2.

Human history is tragically full of examples of massive harm done by sub-sets of the population before a large enough collective collaborates to effectively limit the misunderstandings motivating the incessant harmful pursuits of perceptions of superiority.

I have some comments on this "degrowth" idea. Degrowth can be defined in two parts. Firstly a reduction in rates of economic growth to zero growth. And secondly negative growth which is essentially a reduction in consumption levels. But lets just call them both degrowth for simplicity sake.

Degrowth has multiple consequences. It usefully reduces environmental pressures but it can also cause personal hardship, economic recession / depressions and cause poverty and job losses. This is basic economics. Also refer to the writings of the anthropologist Joseph Tainter. Obviously this depends on how much degrowth and how fast and there is probably a rate of degrowth that the economy can adapt to ( and which I think is desirable) but if you go beyond this the entire economy could collapse quite severely.

Japan has had very low rates of economic growth for decades ( and is doing ok as a society). It looks like we could live with something like zero economic growth, phased in slowly, although I believe poor countries have to be allowed to grow. More rapid and substantial degrowth could be problematic.

Degrowth is also obviously inevitable to some degree sooner or later, because the planets resources are finite and there is huge population pressure on them. Rates of economic growth have been falling steadily in developed countries over the last 50 years from about 6% to about 2.5%, driven by resource scarcity and demographics and market saturation (according to the experts). But deliberately engineering degrowth is another matter, and would obviously not be an election winning policy. If degrowth happens at a moderate pace as a consequence or side effect of carbon taxes that would be ideal.

swampfoxh, yes, I support switching to vegan/vegetarian diets, and yes, I agree that we should be talking about it. But IMO the top priority should still be electing leaders who will push through climate legislation, because the low-hanging fruit is still switchng from fossil fuels to renewables. So far, nothing we've done has affected the trajectory of the Keeling Curve. So we need to push for leaders who will lead on climate.

Of course, individuals are always free to construct their diet as they please, so I certainly agree with the messaging that a vegan/vegetarian diet is another way to decarbonize.

nigelj@37, I get your point when you write "Degrowth is also obviously inevitable to some degree sooner or later." But the problem is that we will blow past any climate-stabilization limits far before we run into material shortages. Unlike a limited food supply that will limit the population of rabbits, there are no limits that I'm aware of that will prevent us from raising Earth's temperature to dangerous levels. Look at Fig. 1. Not only is the Keeling Curve accelerating upwards, but it appears that the acceleration might be increasing (prooving this likely requires more data than is available). The only thing that will avert a crisis is government assistance/intervention. People may fall in line if responsible leaders take the lead, but no amount of messaging will ever be enough, and natural limits are unlikely to save us.

Evan @39, I didnt suggest we just wait for economic growth to slow naturally. I suggested the economy could be deliberately made to contract at moderate rates. The point I'm making is rapid and substantial degrowth would likely cause problems as described. Any disagreement?

There are three main variables: 1)population trends, 2) growth / consumption trends and 3) type of energy being used. I would say its very difficult changing population and consumption trends dramatically for multiple reasons. Its really mostly about a new energy grid, transport and negative emissions technologies. They are going to be hard work but easier than altering population growth rates and consumption levels.

nigelj@40, sorry for not directly dealing with your good question.

"The point I'm making is rapid and substantial degrowth would likely cause problems as described."

I don't disagree. But the situation is this. We are racing to a brick wall not just at high speeds, but accelerating towards this brick wall. And we are discussing if we will spill people's drinks in the car if we step on the brakes.

What I am trying to bring out in these posts is that society is so far out of control, that we need to start putting on the brakes as hard as possible. We will spill many drinks. Nothing short of that will have any chance of achieving Net Zero. What we are essentially saying by what you note (which I don't disagree with) is that because people will only vote for policies that maintain something like the status quo, we must prioritize an orderly slow-down. Which means that we will focus on stabilizing the climate, but not at any particulate level. We will encourage pallatable policies, and just see where it lands us. In other words, we will apply the brakes so as not to spill any drinks, and just see how long the car takes to stop.

That is really what we're doing and will likely continue to do. But we have to try to do better.

Evan @41, I broadly agree with your comments and your articles. I'm just interested in the implications of a degrowth agenda (reductions in gdp growth and consumption) . I'm not a particularly high consumer myself and I have already hugely reduce how much I fly.

I'm looking more at the big picture, and the very ambitious degrowth agendas some people have proposed (eg: 90% cuts in energy use within a decade or two) and I'm pointing out the implications are hugely problematic and much bigger than what these people seem to realise and could be worse than the actual climate problem. Obviously we could get some cuts in consumption without significant problems, but not 90% done at speed or anything remotely like that.

To put things in perspective the great depression of the 1930s involved a big degrowth, an economic contraction, (or cuts in consumption if you prefer,) of 50% at the worst point and this lead to 25% unemployment and dire poverty with no end in sight, ie the trend was accelerating into an unstoppable downwards spiral due to a feedback effect. It took The New Deal together to WW2 to fix the problem. This level of economic contraction is more than spilling a few drinks.

I'm not sure we can risk that again, even if there was a public desire for such levels of degrowth which seems unlikely. Our civilisation is based on high levels of consumption and all our jobs depend on it and unwinding this is going to be very difficult if its even possible.

I'm also not persuaded we actually need such high levels of degrowth / reductions in consumption. It seems intuitively obvious we could fix the climate problem largely with a programme to develop renewables etc,etc, with absolute cuts to consumption that are fairly moderate. We still have about 30 years to get to net zero. If we delay any longer then yes we will be needing bigger and bigger cuts in consumption to the point it becomes politically untenable, and creating a high risk of economic system collapse and mass unemployment as demand is sucked out of the economy at huge scale.

nigelj, I agree that 90% degrowth would cause massive disruption. No question about it. And I'm not saying that is what's needed. I don't know. I am only suggesting that a combination of new technology with lowered consumption is needed. But getting to Net Zero is HUGELY challenging.

What I show in Fig. 2 is not what is referred to as Net Zero in the media. Fig. 2 shows Net Zero Accumulation. What is broadly referred to in the media is Net Zero Emissions, which is more challenging than Net Zero Accumulation, and would result in atmospheric CO2 concentrations decreasing. What I show in Fig. 2 and in Table 1 only shows atmospheric CO2 concentrtions stabilizing.

And we don't have 30 years to do that, but 28. Time flies.

At some point 1.5C will be beyond reach. Then at some point 2C will be beyond reach. If either of these are still within reach today, in 2022, they will only be achieved by revolutionary adjustments to how we live and do business.

Do we have the political will to do that?

Evan @43, yes getting to net zero is hugely challenging whichever way you look at it. Do we have the political will? Doesn't look like it:

www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/feb/16/down-to-earth-joe-biden-climate

Climate catastrophe & the larger ecological crisis is overwhelmingly a consumption problem (caused by a psychological problem) not a population problem. The only ones causing harm are the rich. The only ones growing in numbers are the poor. Population growth in all groups has been slowing for 50 years. Rational population solutions that will be effective in the time we have (9 years) don't exist, but decline in population itself is virtually inevitable as births keep leveling off and death rates rise from the worsening eco-psychological crisis.

Chancel and Piketty note, just 10% of the global population is responsible for around 50% of global emissions.

Kevin Anderson http://kevinanderson.info/blog/a-succinct-account-of-my-view-on-individual-and-collective-action/

I make some of the same points with references in this discussion: https://climatecrocks.com/2020/06/11/ayana-elizabeth-johnson-will-the-ocean-run-out-of-fish/comment-page-1/#comment-115823

The Oxfam Shroom

IPAT is misleading because it assumes every human is an average human. To be accurate & helpful a separate IPAT equation would need to be run on every economic and other group.

[BL] Links activated.

The web software here does not automatically create links. You can do this when posting a comment by selecting the "insert" tab, selecting the text you want to use for the link, and clicking on the icon that looks like a chain link. Add the URL in the dialog box.

J4zonian@45 thanks for your comments. If we remove the 10% wealthiest people in the world, we are still left with 50% of the emissions. That, in itself, is still a climate catastrophe. Yes, the rich consume more. But the people below them still live lifestyles that are not sustainable.

When you say that population growth has been slowing in all groups for 50 years, how do you reconcile that with the numbers that show population growth has been nearly steady at 80,000,000 people/yr for the last 50 years?

I don't doubt that the IPAT equation can be misleading, and I agree that the problem is more complicated because of the distribution of wealth across different sectors of the economy. But I think it broadly shows the relationships and Fig. 2 in this post suggests that at least for the last 100 years, there is a strong relationship between global population and CO2 accumulation rates. Professionaly I work with distributions, so that I understand the difference between an integrated approach from an approach that analyzes effects group by group. But as an engineer I also respect that there are often overall relationships that hold as long as the characteristics of the underlying distributions remain roughly constant. I don't understand Fig. 2 completely, but I consider it very interesting that for the last 100 years there has been some kind of constancy in modern civilization that has CO2 accumulation rates being proportional to global population. Whatever the details, it is frightening.

What's odd is that when I write that we need to consume less, some argue that we cannot push for degrowth. When I write that it is partly a population problem (each person is a carbon emitter), people argue that it is not a general population problem and that the rich contribute more, and ...

So let's agree that the problem is a combination of consumption+population. If wealthy people consumed less and if population stabilized so that global growth stopped, we would likely be much better off.

For the record, I respect Kevin Anderson's work and follow him closely. I'm familiar with the arguments you make as one's that he champions, and even the title of this post is taken from one of his talks.

So we get back to this situation: where is the evidence that it is not too late, and what real alternatives exist to the "spilling people's drinks" as the only criteria we are capable of implementing as individuals, as businesses, as governments, as a species?

I fail to see anything in this discussion that reaches beyond this, which you probably agree with. The primary dynamic driving reduced population grown seems to be by increasing consumption, unfortunately, and knocking off the rich seems pretty unlikely since they are the drivers of misinformation in our global culture, let alone the beneficiaries of consumption, so not sure how that will work.

Don't get me wrong: I firmly believe that we should do everything we can to implement a degrowth strategy: increase the cost of carbon emissions, get renewables to replace fossil fuels, not just compete with them, reduce consumption patterns, elect politicians committed to implementing policies that will increase the pace of the shift, and so on, but from what I can tell, we will be fortunate to just get better at spilling drinks, not slamming on the breaks.

I have spent most of my life promoting sustainable lifestyles, and think that one of the best things folks can do is to look at an even bigger picture: learn as much as they can about the local seasons and cycles of life in the ecosystems they are a part of in order to nurture its health and enable it to survive the bottleneck we are all going through. Aware or not, we are dependent at the capillary level of existence to these parts of our landscape, and if we focused on meeting our needs more by nurturing that relationship, we can actually live more fullfilling lives, reduce our consumption patterns, reduce GGE, and be a significant part of something greater than ourselves in a very visceral, non-abstract way. Reconnecting ourselves and our homes to the planet seems like a silly thing to suggest, but nothing will work in the long run if this isn't part of the equation.

wilddouglascounty "where is the evidence that it is not too late"?

Nobody will ever say, "It is too late." But does Fig. 2 look like a rational scenario? I cannot bring myself to write that it is too late, so what I do instead is to show what we've done and what we need to do, in broad strokes, to stabilize the climate. Fig. 2 and Table 1 are not even as ambitious as the official Net Zero by 2050 goal, and even they seem implausible.

And here is where I'm stuck. My wife and I live in a knock-down house that we bought 25 years ago in our youth, with the idea of building a new house "some day". Now we are in our 60's, and this is "some day". Rebuilding our knock-down house (24 m2 foundation) would be challenging and likely would not survive past our lives, due to building codes that could not be met when we pass it on. So we are looking at building a new house. This means carbon expense. If we build, we are paying the extra money to build a strong house so that it will survive future storms. We will pay the extra money for geothermal HVAC and not use fossil-fuel heating at all. Good things. But I know that as good as we're trying to be, it likely represents an unsustainable carbon footprint.

What do I do? We are genuinely trying to live lives consistent with my writing, but it is really hard. So your message about promoting sustainable lifestyles rings true to me. In our house we designed we built in a root cellar to store fresh food, and we are designing a large garden. The idea is to buy local in bulk and store fruits and veggies, and to grow what we can. I think that part of reducing consumption is people spending more of their liesure time growing what food they can and getting back to cooking from basic ingredients.

So I like your idea very much of reconnecting our homes to the planet. :-)

Congratulations! And by waiting 25 years, you have a clearer picture of what you're going to need now and will be employing people with jobs that are needed to make whatever transition we can muster. If I can suggest some "reconnecting" strategies to your new abode, it would be to follow the slope of your yard to the nearest creek, then introduce yourself to your local watershed basin, creating green corridors whenever possible to link up your land with native habitat, and learn the local cycles and nurture them whenever possible. They are already changing but if you don't know what they are, you won't be able to help nurture them through the inevitable additional changes ahead. And it's a two way street: the life in the land will help those who are listening and helping the land to survive those changes.

It's not too late to continue the fight, it's not too late to help the planet adapt to the changes ahead, and by doing so, we might learn enough to save ourselves. We humans think with a laser-like focus, but when we start paying attention to the rest of the fabric of life that clothes our planet, our task gets easier. It's easier to light a room by opening the drapes rather than trying to make things out with a laser.

wilddouglascounty, I chuckled when I read your response. Yes, 25 years was needed to push our design ideas through the resistant building market.

What we bought 25 years ago is an 80-acre wilderness preserve, dominated by wetlands (that's why we could afford it), with prairie knolls and about 15 wooded acres. Our land sits on a divide, so we interact with two watershed districts as well as the state Department of Natural Resources. We had a grant from the US Fish and Wildlife Service to do restoration work on our land.

We would build our house on a knoll we created, and the water would drain right back into the wetlands. Our land is alredy part of a major green corridor, and we have deer, bear, otter, all manner of birds, etc., in addition to other species. We have Blandings Turtles on our property, and we currently hold the world record for finding the largest Blandings turtle nest (23 eggs).

So yes, we are trying to do the "right" thing, and we are trying to build a house that blends into the surroundings and compliments it rather than dominates it. If we build, we will use the methods we'll employ as teaching tools to help others understand how to build for the future.

When most new American homes have 3 or 4 car garages, we designed our house with a 2-car garage, that is a tuckunder design so that the garage is withing the heating envelope of the house. We therefore use geothermal heat to keep the EV warm in the winter, rather than directly heating the car before using it, as we would in an unheated garage, or sitting outside as it does now. The garage also doubles as a workshop/recreational area. The house is not small by international standards (180 m2 footprint), but there is no separate garage footprint. I also work from home, so the house serves as a workplace. Because we will occupy it starting in our 60's, we designed for wheelchair accessibility. That also causes things to get larger.

I can sit and justify building a new house, but in the end, it pains me to be building something. I wish our current house was more readily fixable, but after 25 years, it is still a knock-down house (by the way, it is 48 m2 not 24 m2 as I incorrectly put in my first comment).