The SCIARA Project – Interactive Time Travel into the Climate Future

Posted on 25 January 2021 by Guest Author

This is a guest blog post by Daniel Tamberg, Potsdam, co-founder and director of SCIARA GmbH. The non-profit organisation SCIARA is developing and operating a flexible software platform for scientific simulation games that allows thousands of players to explore, design and understand possible climate futures together. Decision-makers in politics, business, society can use these games to test climate protection measures for social acceptance in advance, in order to be able to act more quickly and safely to combat global warming.

SCIARA is currently running a crowdfunding campaign to finance the next round of development and refinement after a first Minimal Viable Product (MVP) has been created in the last seven months by a team of software development professionals ten members strong.

Setting the stage

Once the evidence of what was causing the ozone hole had become clear in 1985, it only took a few years to ban the production and use of the responsible chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) after the Montreal Protocol was signed in 1987 and entered into force on 26 August 1989. Replacing the ozone-depleting CFCs was technically easy, and users were not subjected to any significant restrictions as a result of the technological changeover.

Tackling climate change requires global interaction of many complex technical and social solutions. Central industries will be massively affected and are - in some cases - bound to die: first and foremost the fossil energy industry as well as the automotive and aircraft industries, which have provided unprecedented prosperity in the past. And the lifestyle of billions of people will need to change.

Any politician or business leader who takes early and decisive action on climate change risks losing voters, customers, investors, and supporters - see French President Macron’s experience with the Yellow Vests. Those who act too late or too hesitantly, on the other hand, become responsible for the catastrophic effects of climate change in the future.

“Yellow Vest” protests after fuel prices were raised in France in 2019, Elekes Andor CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

My hypothesis: We know enough about the existence, cause, consequences and impacts of climate change as well as about possible technological, systemic and societal solutions. The social acceptance of climate protection measures has become the decisive impediment to solving the climate crisis. The lack of acceptance is expressed through non-compliance with regulations, at the ballot box and through protests, riots and, in extreme cases, even insurrection.

How can governments and corporate leaders reduce uncertainty about the response of people affected, find the most socially acceptable solutions and strategies to introduce them, and thus make confident decisions about climate action?

One would have to be able to see into the future. But who can?

Visualizing climate futures

Insufficient strategies to identify climate change solutions

Insufficient strategies to identify climate change solutions

Previous strategies such as expert interviews, studies and surveys apparently do not work well enough for this. And even the most sophisticated so-called social-ecological agent-based simulations, which attempt to bring together models of human behaviour with models of our natural environment, do not achieve sufficiently realistic results to be able to narrow down the likely behaviour of real citizens.

The crucial shortcoming of these models: people are mapped into formulas and algorithms and some essential drivers of social dynamics are not mapped at all, for example the discursive communication of the modelled human actors.

Common types of models used to study societal climate impacts

Common types of models used to study societal climate impacts

This is where SCIARA comes in. Instead of trying to refine software models of human behaviour further and further in the hope of one day creating a realistic representation of humans in computers, we take a shortcut: we replace software-driven actors in social-ecological-technological simulations with real people.

For the players of these simulations, who can participate free of charge and anonymously, it looks like a browser-based massively multiplayer online game. The backend with the models runs on cloud-based servers, maintained by the SCIARA organisation.

Playing the game

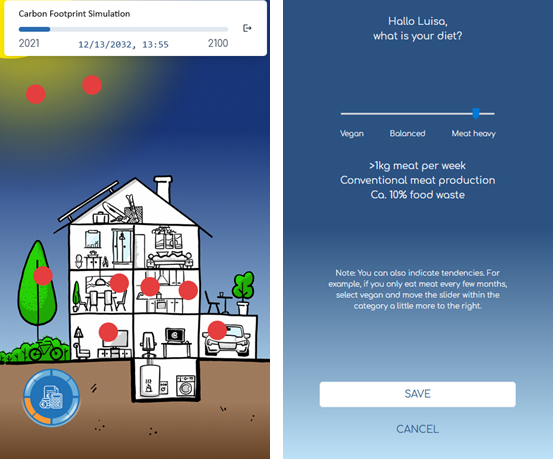

In a first of many possible simulation scenarios, players roll forward their current lifestyle in all areas that are important for the climate. To do this, they adapt their future lifestyle to their changing needs, new rules and the state of the world whenever they want. Important areas on which players make decisions are, for example, mobility, diet, housing, consumption, leisure, investments, travel and recycling and their political orientation.

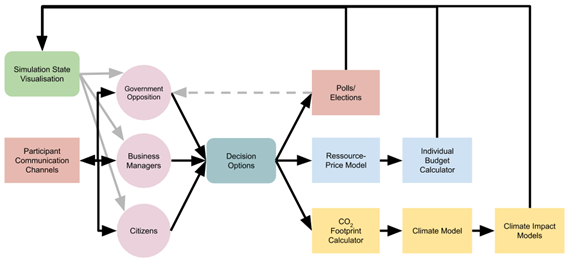

Simple SCIARA information flow schematics (click for larger version)

Simple SCIARA information flow schematics (click for larger version)

The system constantly visualises the collective progressive effects of all participants' decisions on the planet and society. These include, for example, sea level rise, crop failures and extreme weather events, but also bank balances, the results of elections and perhaps economic growth. Wherever necessary, these feedbacks are calculated by scientific models provided by major science partners..

Realistic trade-offs arise for players because, even in the simulation, they only have a limited income and assets, they want to live healthily for a long time, and perhaps freedom and the amount of free time they have at their disposal are particularly important to them.

Screenshots from the current development version of SCIARA - the red dots on the screen give access to various corresponding information or decision options, like diet.

Screenshots from the current development version of SCIARA - the red dots on the screen give access to various corresponding information or decision options, like diet.

In addition, players meet and interact with other simulation participants about the world and their decisions in the game. They do this in simulated places such as their homes, neighbourhoods, workplaces, pubs, transport and many more.

Complementing their direct perception of the simulated world, AI-generated virtual media of various flavours give players a realistically "filtered" view of the wider simulated world and the events in it.

The "goal" of the game is to live the best life possible in the simulation under the given and evolving circumstances - according to players’ own standards, values and needs. To do this, it is necessary to constantly adapt one's own lifestyle to the changing climate and climate protection measures introduced, and to balance the conflicting goals that arise in the process.

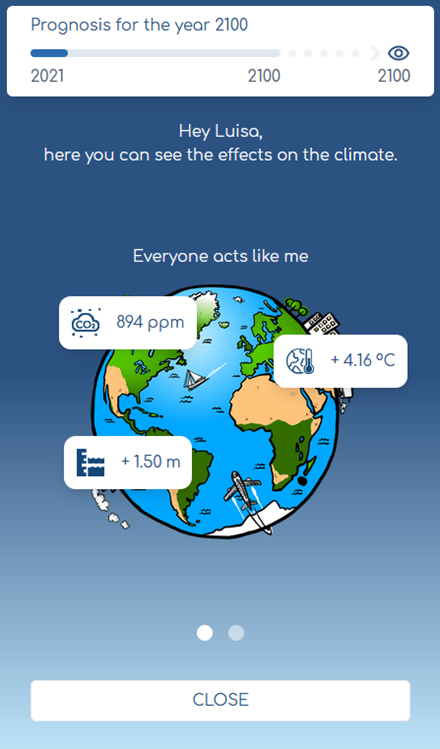

This is a prognosis screen - how would the climate look in 2100 if everybody would live like I do? We want to visualize the numeric values in a more tangible way in the future, like stating which cities will be inundated by the given sea level rise.

This is a prognosis screen - how would the climate look in 2100 if everybody would live like I do? We want to visualize the numeric values in a more tangible way in the future, like stating which cities will be inundated by the given sea level rise.

The time players spend participating in a simulation run varies depending on how deeply they immerse themselves in the virtual world and how much players communicate with the other participants in it. We assume between 2 and 60 minutes per day, over several days or weeks for a simulation run. And new simulation runs will keep coming out with changed conditions, so participation never gets boring.

In this test environment, decision-makers in politics, business and science can check the social reaction to climate protection measures - with realistic social dynamics over time. In this way, they can distinguish laws, regulations and products that are likely to be socially viable from those that would fail due to societal resistance. This helps to weigh risks and opportunities and to act quickly, effectively and sustainably in favour of the climate.

Supporting SCIARA

SCIARA was founded by Sebastian Kutscha and myself. So far, six medium-sized German IT companies have become partners and have invested money and provided team members. A seventh company will soon join as a partner.

The development is done in close cooperation with the renowned Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research as well as leading scientific institutions in Spain, Italy, Slovenia, Switzerland and the USA, which provide the models and work with us to answer the social science questions (e.g. participant recruitment, representativeness, realistic behaviour, citizen science approach, evaluation) properly.

How about supporting SCIARA by participating in the simulations, by supporting the crowdfunding campaign on StartNext, by spreading the idea and the campaign in your networks - or even as a customer who wants to test a climate protection measure?

Note: SCIARA is pronounced "skiara" with a hard "k" (not "shiara") and is an acronym for Society-Climate Interaction Analysis with Real Agents.

Arguments

Arguments

A fascinating effort to exploit new capabilities to produce policy guidance. We're bound to learn something of interest from this project.

I'm wondering how players will be selected for participation, or if they will select themselves.

If self-selected, how will simulation results account for self-selection bias?

It may be (is probably?) the case that fully self-selected participants will more or less converge on a population with proclivities not faithfully reflective of information, attitudes and beliefs of a more complete sample of the general population.

As well, drop-outs during the course of the game could result in a further distillation of users more divergent from the general population.

The resulting group of participants may feature unusual levels of information on various details of climate change, climate solutions. As well, they may not be reflective of general atittudes toward and acceptance of policy interventions, necessities for lifestyle changes etc.

If indicators for paths forward assessed by participation of such an unrepresentative subsample are then applied to the general population in the form of policy, incentives etc., there is a strong chance that misalignment due to the original self-selection will become visible, with acceptance and support projected by the game not mirrored in the real world.

I suspect that consumers of iinformation provided by the game in the political and policy realms will be aware of this risk.

How will self-selection be controlled for?

For readers wanting to learn more about the limitations of previous efforts mentioned by Daniel, a nice example is The Climate Action Simulation, Rooney-Varga et al, 2019 (open access). As is often the case, the supporting citations in this paper are of great value as a means of gaining at least a tenuous foothold on this domain, as valuable in their own way as the actual investigation described.

Dear doug_bostrom, the question of self-selection bias is always about the first one we are asked. ;-)

There will be two contexts in which a SCIARA simulation can run:

My only requirement would be to show the participants how representative a sample the simulation is running with, so they are not misled to believe that the outcome is "the truth".

There are several levels on which we can work to improve representativity:

The application of this technique is limited by the effects of skewed social dynamics if some population groups are strongly over- or underrepresented, as communication between participants cannot be statistically corrected.

Thanks very much for taking the time to elaborate, babelsguy.

I'm not surprised to hear confirmed your most common "FAQ." :-)

It seems as though the nut of the challenge lies in "3," that being the axle on which validity and hence utility of results will spin.

Is it the case that participation will be fully open to all comers, regardless of directed recruitment? I suppose a fairly detailed intake survey will be helpful, to successfully apply "7" and especially if participation is wide open.

And just to clarify, I'm all for this project. It's surely going to be useful. Keen to see the outcome be useful input for politicians and policy formulation.

@doug_bostrom, thank you for the kind exchange. I very much appreciate it.

Recruitment is wide open, and every particpant needs to go through some socio-demographic screening.

Otherwise we could never select representative samples or measure representativity in the first place.

Of course, we will make sure that this data and the behavioural data from the experiments cannot be connected to individual user accounts by simply stealing our database. ;-)