The 2010 Amazon Drought

Posted on 6 February 2011 by Andy Skuce

A short paper by Simon Lewis, Paulo Brando and three co-authors, just published in Science Magazine, reports on the 2010 drought in the Amazon Basin. This drought occurred only a few years after the exceptional drought of 2005, which was supposed to have been a one-in-a-hundred-year event. The paper presents evidence that last year's drought was both more severe and more extensive than the earlier one.

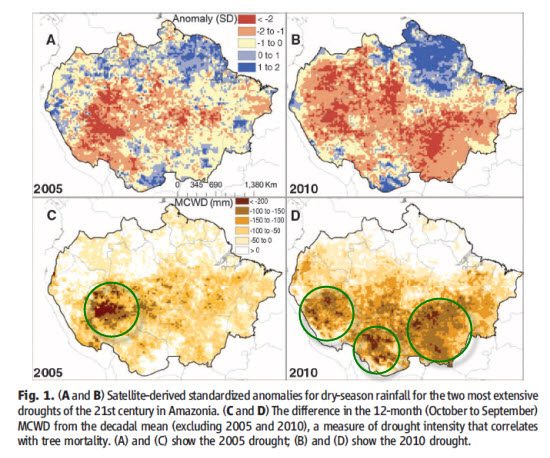

Figure from Lewis (2010) with annotation added.

Using data from satellites, the red-blue maps compare the rainfall in the dry seasons of 2005 and 2010. The "maximum climatological surface water deficit" (MCWD) is a factor that more accurately predicts the amount of stress that the trees endure in a drought and is shown in the lower, brown-colored couple of maps. The zones with the most severe expected drought damage are highlighted by green circles, added here to the original published figure. There was a dry zone observed in both droughts in the southwest of the Amazon basin. The 2010 drought affected two additional affected areas, one in the south of the Basin, in Northern Bolivia and another in the southeast, in Mato Grosso State, Brazil.

Droughts reduce the rate of tree growth and repeated droughts may cause trees to die off altogether. Forest fires are also more likely during unusually dry periods and in 2010 extensive fires were reported in Northern Bolivia . All these effects combine to make the Amazon basin in 2010 into a source of carbon rather than a net sink Simon Lewis and his co-workers calculated that the impact of the 2010 drought amounted to an effective net transfer of 2.2 gigatonnes (billion tonnes) of carbon from the biomass to the atmosphere.

To put this into perspective, 2.2 gigatonnes is comparable to the emissions resulting from fuel burning in 2008 from India and China combined, according to the IEA. One dry year in the Amazon, therefore, may have made as big a contribution to greenhouse gasses as the annual contribution of the two largest developing economies. Last year, the lungs of the world were breathing out carbon when we would have preferred them to be breathing it in.

Droughts in the Amazon tend to occur at the same time as sea surface temperature anomalies in the Pacific (El Niño) and in the Atlantic Oceans. Climate models predict an increase in the frequency and severity of both ocean temperature anomalies and droughts in the Amazon. On the other hand, the two exceptional droughts that occurred in quick succession might just represent unusual weather years and, if there were a return to normal rainfall patterns, the forests might recover quickly. But if the climate model predictions are correct, we should expect additional severe Amazon Basin droughts over the coming decades.

One of the slow positive feedbacks to climate change--the great Amazonian forests starting to emit, rather than continuing to absorb carbon--may be kicking in more quickly than we previously feared (for example, see Cox et al 2000}.

The BBC has produced an excellent short video report on this story.

Hat-tip to Dorothy Cutting.

Arguments

Arguments

0

0  0

0 Since 1935, the terrestrial biosphere has been acting as a carbon sink, Some of this sequestration has been taking place in Amazonia, at least for part of this time, but the majority of the sink is probably happening in high northern latitudes, through reforestation and increased plant growth in the tundra. This continuing negative feedback may make us feel better but our sense of relief may be short lived if factors like forest fires, melting permafrost or pine beetles start to play a bigger role.

Since 1935, the terrestrial biosphere has been acting as a carbon sink, Some of this sequestration has been taking place in Amazonia, at least for part of this time, but the majority of the sink is probably happening in high northern latitudes, through reforestation and increased plant growth in the tundra. This continuing negative feedback may make us feel better but our sense of relief may be short lived if factors like forest fires, melting permafrost or pine beetles start to play a bigger role.

El-Nino causes drought in the Amazon by shifting the convective area over to the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, where the SST's along the South American coast are ramping up. Once again the rain-making shifts toward the area of greater sea surface temperatures.

The connection between drought/wet episodes in the Amazon are very consistent throughout the 20th century. 16 out 17 El- Nino caused drought, and 14 out of 16 La Nina caused wet episodes in the Amazon. See Ropelewski & Halpert 1987. The figure jumps higher when the 1990's Amazonian droughts are included.

El-Nino causes drought in the Amazon by shifting the convective area over to the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean, where the SST's along the South American coast are ramping up. Once again the rain-making shifts toward the area of greater sea surface temperatures.

The connection between drought/wet episodes in the Amazon are very consistent throughout the 20th century. 16 out 17 El- Nino caused drought, and 14 out of 16 La Nina caused wet episodes in the Amazon. See Ropelewski & Halpert 1987. The figure jumps higher when the 1990's Amazonian droughts are included.

but we'll probably find out in the next 5 years or so if we start getting large El Ninos contrary to the diminished El Ninos that we would expect from a natural cycle.

but we'll probably find out in the next 5 years or so if we start getting large El Ninos contrary to the diminished El Ninos that we would expect from a natural cycle.

-- Figure 7 from Dai et al 2004

Maps of linear trends of PDSI [change (50 yr), calculated with both precipitation and temperature changes] during (top) 1900–49 and (middle) 1950–2002. (bottom) The trends of PDSI calculated without temperature changes. Red (blue) areas indicate drying (wetting).

The more recent 50 years sure look more severe than the prior 50. The graph ends in 2002, the beginning of the most recent 100 year events in the Amazon.

The authors conclude:

Our PDSI results, which are based on atmospheric moisture supply and demand near the surface, are consistent with increased evaporation under greenhouse gas–induced warming, as predicted by comprehensive coupled climate models. Global temperature increases have become pronounced after the 1970s and have been attributed to human-induced climate changes arising primarily from increased greenhouse gases.

-- Figure 7 from Dai et al 2004

Maps of linear trends of PDSI [change (50 yr), calculated with both precipitation and temperature changes] during (top) 1900–49 and (middle) 1950–2002. (bottom) The trends of PDSI calculated without temperature changes. Red (blue) areas indicate drying (wetting).

The more recent 50 years sure look more severe than the prior 50. The graph ends in 2002, the beginning of the most recent 100 year events in the Amazon.

The authors conclude:

Our PDSI results, which are based on atmospheric moisture supply and demand near the surface, are consistent with increased evaporation under greenhouse gas–induced warming, as predicted by comprehensive coupled climate models. Global temperature increases have become pronounced after the 1970s and have been attributed to human-induced climate changes arising primarily from increased greenhouse gases.

Comments