At a glance - The runaway greenhouse effect on Venus

Posted on 30 January 2024 by John Mason, BaerbelW

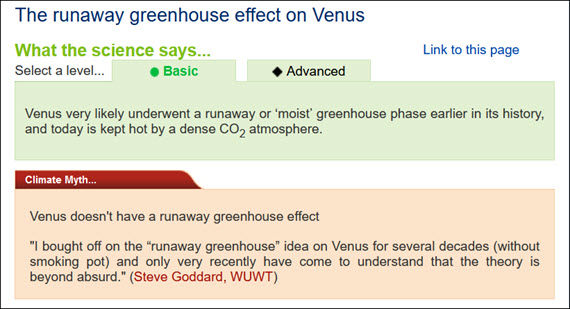

On February 14, 2023 we announced our Rebuttal Update Project. This included an ask for feedback about the added "At a glance" section in the updated basic rebuttal versions. This weekly blog post series highlights this new section of one of the updated basic rebuttal versions and serves as a "bump" for our ask. This week features "The runaway greenhouse effect on Venus". More will follow in the upcoming weeks. Please follow the Further Reading link at the bottom to read the full rebuttal and to join the discussion in the comment thread there.

At a glance

Earth: we take its existence for granted. But when one looks at its early evolution, from around 4.56 billion years ago, the fact that we are here at all starts to look miraculous.

Over billions of years, stars are born and then die. Our modern telescopes can observe such processes across the cosmos. So we have a reasonable idea of what happened when our own Solar System was young. It started out as a vast spinning disc of dust with the young Sun at its centre. What happened next?

Readers who look up a lot at night will be familiar with shooting stars. These are small remnants of the early Solar System, drawn towards Earth's surface by our planet's gravitational pull. Billions of years ago, the same thing happened but on an absolutely massive scale. Fledgeling protoplanets attracted more and more matter to themselves. Lots of them collided. Eventually out of all this violent chaos, a few winners emerged, making up the Solar System as we now know it.

The early Solar system was also extremely hot. Even more heat was generated during the near-constant collisions and through the super-abundance of fiercely radioactive isotopes. Protoplanets became so hot that they went through a completely molten stage, during which heavy elements such as iron sank down through gravity, towards the centre. That's how their metallic cores formed. At the same time, the displaced lighter material rose, to form their silicate mantles. This dramatic process, that affected all juvenile rocky planets, is known as planetary differentiation.

Earth and Venus are the two largest rocky planets. But at some point after differentiation and solidification of their magma-oceans, their paths diverged. Earth ended up becoming habitable to life, but Venus turned into a hellscape. What happened?

There's a lot we don't know about Venus. But what we do know is that the surface temperature is hot enough to melt lead, at 477 °C (890 °F). Atmospheric pressure is akin to that found on Earth - but over a kilometre down in the oceans. The orbit of Venus may be closer to the Sun but a lot of the sunlight bathing the planet is reflected by the thick and permanent cloud cover. Several attempts to land probes on the surface have seen the craft expire during descent or only a short while (~2 hours max.) after landing.

Nevertheless, radar has been used to map the features of the planetary surface and analyses have been made of the Venusian atmosphere. The latter is almost all carbon dioxide, with a bit of nitrogen. Sulphuric acid droplets make up the clouds. Many hypotheses have been put forward for the evidently different evolution of Venus, but the critical bit - testing them - requires fieldwork under the most difficult conditions in the inner Solar System.

One leading hypothesis is that early on, Venus experienced a runaway water vapour-based greenhouse effect. Water vapour built up in the atmosphere and temperatures rose and rose until a point was reached where the oceans had evaporated. In the upper atmosphere, the water (H2O) molecules were split by exposure to high-energy ultraviolet light and the light hydrogen component escaped to space.

With that progressive loss of water, most processes that consume CO2 would eventually grind to a halt, unlike on Earth. Carbon dioxide released by volcanic activity would then simply accumulate in the Venusian atmosphere over billions of years, creating the stable but unfriendly conditions we see there today.

Earth instead managed to hang onto its water, to become the benign, life-supporting place where we live. We should be grateful!

Please use this form to provide feedback about this new "At a glance" section. Read a more technical version below or dig deeper via the tabs above!

Click for Further details

In case you'd like to explore more of our recently updated rebuttals, here are the links to all of them:

If you think that projects like these rebuttal updates are a good idea, please visit our support page to contribute!

Arguments

Arguments

Comments