Agnotology, Climastrology, and Replicability Examined in a New Study

Posted on 28 June 2013 by dana1981

A new paper is currently undergoing open public review in Earth System Dynamics (ESD) titled Agnotology: learning from mistakes by Benestad and Hygen of The Norwegian Meteorological Institute, van Dorland of The Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute, and Cook and Nuccitelli of Skeptical Science. ESD has a review system in which anybody can review a paper and submit comments to be considered before its final publication. So far we have received many comments, including from several authors whose papers we critique in our study, like Ross McKitrick, Craig Loehle, and Jan-Erik Solheim. We appreciate and welcome all constructive comments; the discussion period ends on July 4th.

Agnotology is the study of how and why we do not know things, and often deals with the publication of inaccurate or misleading scientific data. From this perspective, we attempted to replicate and analyze the methods and results of a number of climate science publications.

We focused on two papers claiming that factors other than human greenhouse gas emissions are responsible for the global warming observed over the past century – specifically, the orbital cycles of various planetary bodies in the solar system. Since there is no physical reason to believe that the orbits of other planets should have any significant effect on the Earth's climate, and these papers generally do not propose a physical mechanism behind this supposed influence, this hypothesis is often referred to as "climastrology," because it's essentially an application of astrology to climate change.

In our study, we attempted to replicate the methods and results in these and a number of other papers to evaluate their validity. In the process, we found many different types of errors that can appear in any paper, but that appear to be common to those which purport to overturn mainstream climate science.

Curve Fitting

One common mistake we highlighted in our paper is known as 'curve fitting'. This is an issue we have previously discussed at Skeptical Science, for example in papers published by Loehle and Scafetta. The concept behind 'curve fitting' is that with enough fully adjustable model parameters that are not limited by any sort of physical constraint, it's easy to make the model fit any data set. As the famous mathematician, John von Neumann said,

"With four parameters I can fit an elephant, and with five I can make him wiggle his trunk."

However, a model without any sort of physical limitations is not a useful model. If you create a model that attributes climate changes on Earth to the orbital cycles of Jupiter and Saturn as Scafetta did, but you don't have any physical connection between the two or any way to know if your parameters are at all physically realistic, then you really haven't shown anything useful. All you've got is a curve fitting exercise.

Omitting Inconvenient Data

Similarly, Humlum et al. (2011) attempted to attribute climate changes on Earth to lunar orbital cycles. In addition to the same curve fitting issues, we also found that they neglected data that did not fit their model. Humlum et al. claimed that their model could be used to predict future climate changes, but in fact we found that it could not even accurately reproduce past climate changes.

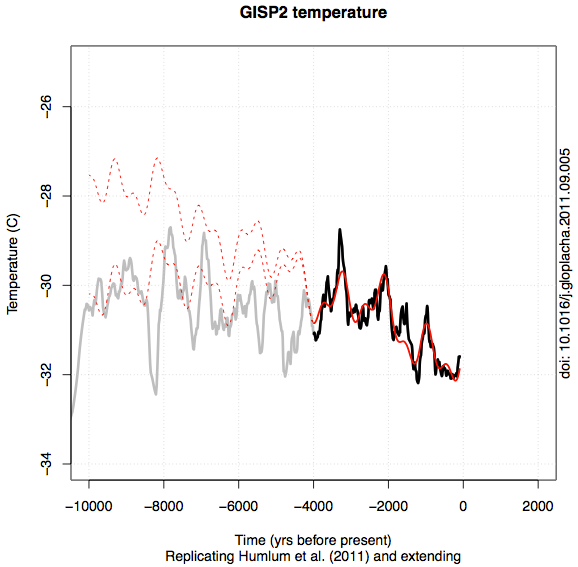

They fit their model to temperature data from Greenland ice cores (GISP2) (which is a problem in itself, since Greenland is not an accurate representation of global temperatures) over the past 4,000 years. However, the data are available much further back in time. We extended the Humlum model, and found it could not reproduce Greenland temperature changes for the prior 6,000 years. Even when we fit the observed data as best as we could by removing the trend in the 4,000-year model, the model still produced a poor fit (Figure 1).

Figure 1: A replication of Humlum et al. (2011a)’s model for the GISP2-record (solid red) and extensions back to the end of the last glacial period (red dashed). The two red dashed lines represent two attempts to extend the curve fit, one keeping the trend over the calibration interval and one setting the trend to zero. The black curve shows the part of the data showed in Humlum et al. (2011a) and the grey part shows the section of the data they discarded.

Many Other Examples

We examined many other case studies of methodological errors in the appendix of our paper.

- Case 3: Loehle and Scafetta (2011) - unclear physics and inappropriate curve-fitting

- Case 4: Solheim et al. (2011) - ignoring negative tests

- Case 5: Scafetta and West (various) - wrongly presumed dependencies and no model evaluation

- Case 6: Douglass et al. (2007) - misinterpretation of statistics

- Case 7: McKitrick and Michaels (2004) - failure to account for the actual degrees of freedom

- Case 8: Veizer (2005) - missing similarities

- Case 9: Humlum et al. (2013) - looking at wrong scales

- Case 10: Cohn and Lins (2005) - circular reasoning

- Case 11: Scafetta (2010) - lack of plausible physics

- Case 12: McIntyre and McKitrick (2005) - incorrect interpretation of mathematics

- Case 13: Beck (2008) - contamination by other factors

- Case 14: Miskolzi (2010) - incomplete account of the physics

- Case 15: Svensmark, Friis-Christensen, and Lassen (various) - differences in pre-processing of data

- Case 16: Svensmark (2007), Shaviv (2002), and Courtillot et al. (2007) - selective use of data

- Case 17: Yndestad (2006) - misinterpretation of spectral methods

All the results of our paper through Case 10 will be available in an R-package in which we replicate the results of the studies in question.

Conclusions

The main point of our paper is to show that studies should be replicable and replicated. The peer-review process is a necessary but insufficient step in ensuring that published studies are scientifically valid. Sometimes flawed papers are published. We also note the usefulness of including open source codes and data, as we have done, to allow for replication of a study's results.

Frequently, a paper that purports to overturn our previous scientific understanding is immediately amplified in the media, and can serve to misinform the public if the results are incorrect. There was recently a good example of this in the field of economics, where an attempt to replicate a paper's results revealed a mistake that entirely undermined its conclusions. However, before the attempt was made to replicate the study, its conclusions were widely used to justify a number of economic policies that now appear to have been ill conceived.

This example highlights the importance of replication and replicability prior to putting too much weight on the results of any single study. It can be tempting to immediately accept the results of a study which confirms our pre-conceived notions – that's true of everybody, not just climate 'skeptics' – but it's important to resist that urge and first make sure the study's results are replicable and accurate.

Arguments

Arguments

Somewhat on the topic of how we know what we think we know, this was something interesting I came across recently.

Changing Minds About Climate Change Policy Can Be Done -- Sometimes

I suppose it depends on the mentality of the person. Some get confused by conflicting information. Personally, I tend to withhold judgement until I have heard a differing opinion; it doesn't matter if it is climate change or an argument between two children.

Interesting - perhaps one lesson is to accept the notion that:

"We need each other to keep our selves honest."

This sounds like a very, very interesting paper. Looking forward to seeing the comments from the various authors that are being "audited" as well. Great work!

The interactive comments are highly entertaining. There should be a separate post just on those comments.

DSL, I only read a couple of the responses, but yeah, it seems that in addition to the need to avoid confirmation bias, there is a complementary need to avoid dis-conformation(?) bias, the bias against understanding an argument correctly the conclusion is contrary to existing beliefs.

I read them and I think, "You are arguing with something that was not said."

Close scrutiny of the 3%?

I vacillate between thinking it's best not to draw too much attention to them, on the basis that any publicity will lift their profiles, and thinking an expose of their bad science can only damage the denialist cause. On the basis that more and better information is best, I've decided to pump for the latter.

Auditing the "auditors". How audacious! The response from Hanekamp that invents a criteria of symmetry is delicious in an ironic sense then, that it's somehow unfair to systematically demonstrate common classes of logical, statistical and factual errors in the work of those seeking to do the same with regard to mainstream climate science. O- the humanity!

Hanekamp is an interesting case, especially if you can trust things you find with google:

http://www.zoominfo.com/p/Jaap-Hanekamp/11461458

http://www.climatewiki.org/wiki/Heidelberg_Appeal

Apparently, Heidelberg Appeal no longer exists, but there is a new one called the "Green Audit Institution" (difficult to translate "Groene Rekenkamer"):

http://www.groenerekenkamer.com/node/877

I wonder if this is the Dutch equivalent to the organisation "klimarealistene" which we discuss in our paper? Anyhow, his comment speaks for itself...

Nice job LOL.

But how could you leave out my personal favorite climastrologist - Dr Theodor Landscheidt? I mean after all, His work with Gleissberg cycles and the sun's barycentric oscillations explains it all.

See fig 8 in this fine paper (published in E&E).

Keep up the good work,

arch

I have been following things over at RC and ESDD comment section... Deliciously wicked!

Whether it has anything to do with agnotology, I am not qualified to say, but it has everything to do with proper science and the essence of peer review.

Rasmus, De Groene Rekenkamer is indeed the equivalent of the klimarealisterne. Hanekamp is linked to CFACT also, so there's little to expect from him in terms of scientific objectivity.

Should have added:

It woudl seem as if the experience of the Wegman report would be a fitting epilogue....

I sampled some more of the comments. I think it would be painting with too broad a brush to say that there is deliberate intent behind all the mistakes that are being made. The human mind is not a computer; emotion interfers with rational processing. Because of the huge stakes involved, it is difficult to avoid getting emotional when discussing climate science. I believe that some of the dissenters truly believe what they are saying; they are not being dishonest; they are just wrong.

I'm thinking of an analogy of students learning some difficult math process. (Substitute whatever your consider difficult: geometry, trigonometric substitution, discrete statistics, etc.) There are mistakes that are made by the set of students, and some are more common than others. There are patterns to the mistakes.

It is emotionally difficult to deal with the reality of our situation, and there are many mistakes that can be made that enable one to conclude that our situation is better than it really is. I see this paper as an attempt to identify the more common patterns of errors, but to conclude that the mistakes are intentional is perhaps a step too far.

Yes, I know that there have been many times when the mistakes have been pointed out and yet the mistakes are continued, but I've seen the same thing with cancer, COPD, and Alzheimer's among different family members. No matter how you lay out the information and the conclusions, the person refuses to accept that they have a serious problem and that not dealing with the problem is going to end up being worse for them.

The summary of what I am saying is that often when people are wrong, they are not wrong because they have nefarious intent or lack the skill to come to a correct conclusion. They are wrong because the correct conclusion is simply too threatening, and their emotional, and subconscious part, of their mind will not let them come to grips with the reality of the situation. With climate change, two of the most common threats as I see them are the thoughts, "I have really hurt my children's prospects for health and well-being.", and "I will be ostracised from my group." With a great many people, either of those is all the emotional motivation anyone needs to cause a cognitive gear slip. (No, I am not so naive as to think there are not people who would lie for money; I just think it is less common than some believe.)

Where do these guys learn their stuff? In my first year applied maths course, a lecturer told us that interpolation can give useful results, but extrapolation should be treated with extreme caution -- if it purely amounted to curve fitting.

I also recall the mantra "correlation is not causation" from the denial camp when the theory of climate change was a bit less complete than it is now. Funny how the argument they used then against the theory almost entirely applies now to them.

A deep fundamental problem in public perception of science is the desire of the media to portray the big breakthrough. This very rarely happens and may only be recognised in retrospect after a lot of retries of an apparently failed experiment.

In the interactive comments for review of this paper, in a reply by Rasmus ("SC C292: 'Reply to Ellestad/Solheim/"klimarealistene"', Rasmus Benestad, 25 Jun 2013"), there is a reference to a scanned copy of a letter:

The link provided does not work. Is the scanned copy still available anywhere? Thanks!

Can you say anything on the prcoess from here and guess at schedule?

Skeptical Science has a particular interest in communication techniques... this paper seems to represent an instance of a new experiment in communication across the divide with writers who deny conventional aspects of climate science.

The reviews and responses are also an interesting study. in communication problems. The nature of the subject matter is going to make it hard to get a reviewer who has relevant expertise but does not have a personal stake in the subject.

It's amusing to see insulting content clothed in terms of politie discourse. The classic is where Hanekamp adds an extra comment just to say: "I would like to thank Ben-estad et al. for the exchange with me. It has given me a wealth of information for my philosophy classes."

The appropriate response would be, I suggest, be along the lines of: "We are delighted that these exchanges will be of use to your philosophy students. Indeed, we'd be willing to come and give a guest lecture on the matter, which would doubtless be of considerable benefit to your students."

I find the comment by Chris G very interesting. I agree that many people probably believe what they are saying, certainly many lay people who get their (mis-)information from "skeptical" websites or friends, do seem to believe what they are saying.

However, it is also true IMHO that when one is exposed to an enormous amount of fact contrary to one's viewpoint, one does usually concede the point or at least retreats, i.e. stops arguing the obviously false. To take ChrisG's analogy: Certain mistakes made by students may be common, but those same students sooner or later realize their mistakes and either switch major or stop making the same mistakes and learn ...

Not true for a large group if not all "contrarians". They insist on making the same mistakes using the same false logic over and over and over again. Solheim and Ellestad from Klimarealistene are prime examples. They cannot be called "wrong" any more, they clearly behave like/are denialists, only clothing themselves as "skeptics"; and I think the ESDD paper comments (again) show that. When I exposed Ellestad's denialist methods online, he simply repeated the same tactics in reply, very similar to his comment on this manuscript. No evidence, no coherent argument, only rhetoric ala "everybody knows that the Hockey Stick is broken".

I have trouble believing that people like Ellestad have simply "slipped a gear", as seemingly that is what Chris G suggests in his last paragraph. The difference is between ordinary denial, well researched in pschycology and underlying the examples given by Chris G, and denialism as defined by Chris Hoofnagle as

The latter is clearly employed by Klimarealistene and others, and, as a result, does warrant a search for evidence that they, as others, "intentionally" make mistakes in trying to disprove the facts. This paper makes a large step in that direction, kudos to Benestad and colleagues.