Correction to the True Cost of Coal Power - MMN11

Posted on 16 October 2011 by dana1981

We recently published a post on a study which examined the external costs of air pollution associated with various industries (costs which are not reflected in the market price), including power production through coal combustion, written by economists Muller, Mendelsohn, and Nordhaus (2011; MMN11).

Social Cost of Carbon

The costs associated with climate change are estimated through the "social cost of carbon" (SCC). Normally the SCC is estimated in terms of CO2-equivalent emissions, because CO2 isn't the only long-lived greenhouse gas causing global warming, and carbon pricing systems usually include other greenhouse gases as well. As we have previously discussed, although it's a difficult value to estimate, in recent climate economics studies, the SCC is usually put between about $5 to $68 per ton of CO2-equivalent emissions.

In their study, MMN11 estimated SCC at between $6 and $65 per ton, with a central value of $27 per ton. Given that SCC is normally defined in units of $ per ton of CO2-eq, and that their range of values was similar to other recent estimates, I assumed their SCC range was also listed in $ per ton CO2-eq.

When You Make Assumptions, You Make an...

Alas, no! Joe Romm has pointed out that MMN11 use SCC units of $ per ton of carbon emitted. In order to convert their SCC estimates to $ per CO2-eq, we must divide by 3.67, which changes their estimates to $1.63 to $17.71 per ton of CO2, with a central value of $7.36 per ton. Note that this puts the MMN11 central estimate of SCC near the lower limit we have seen in recent economic studies!

SCC Depends on Discount Rate

The SCC value depends heavily on the 'discount rate' which is effectively how much more we value money now than in the future, and is related to interest rates. The larger the discount rate, the less we value the future, and thus future climate change does that much less relative economic damage. Less economic damage = lower social cost of CO2 emissions.

Some "skeptic" economists - most notably Richard Tol - have argued for a very high discount rate, which then allows them to argue that future economic damage from climate change will be relatively small. Australian Economist John Quiggin has noted that much higher discount rates like those implemented by MMN11 are tantamount to telling future generations that they "can go to hell for all we care," since high discount rates place much lower weight on the welfare of future generations.

A study by the New York University School of Law's Institute for Policy Integrity considered discount rates ranging from 2% to 5%, which results in the SCC range of $5 to $68 we referenced above (note that's in 2007 dollars, and grows over time). The MMN central estimate of $7.36 per ton of CO2 is equivalent to a discount rate of approximately 5%, which is fairly high. A more commonly-used discount rate of 3% results in an SCC of $36 per ton of CO2 in 2010 dollars. Note that this rather mainstream value is more than twice the upper bound of the range of SSC values considered by MMN11 ($17.71 per ton of CO2).

Difference Between MMN11 and Epstein 2011

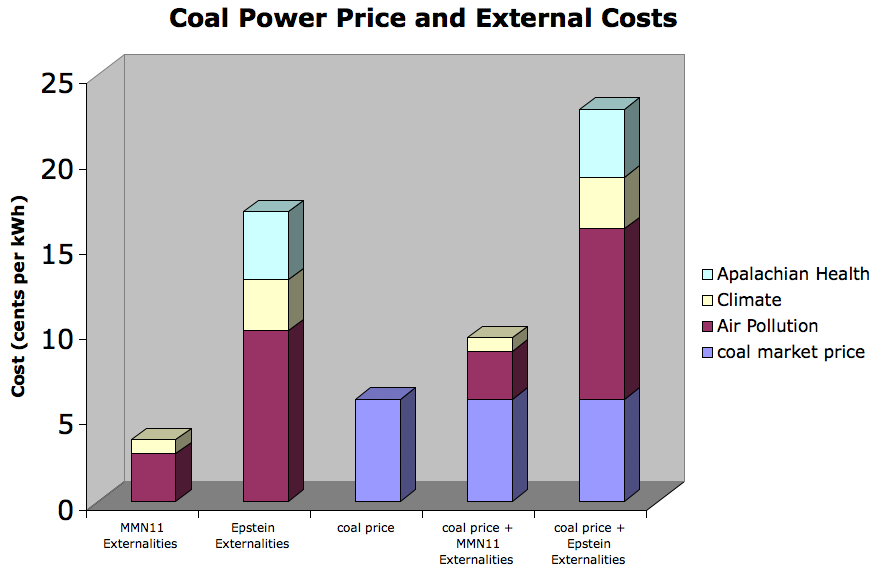

In our post on MMN11, we noted that their estimates of the external costs of coal emissions were more than 3 times lower than the estimates in Epstein et al. (2011) (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Average US coal electricity price vs. MMN11 and Epstein 2011 best estimate coal external costs.

The SCC discrepancy accounts for the difference in climate externality estimates. Epstein et al. used an SCC value of $30 per ton of CO2, where as MMN11 used $7.36 per ton of CO2. The Epstein et al. value is much more realistic and consistent with current-day SCC estimates, but even $30 per ton of CO2 is likely on the low side. In fact, a recent Economics for Equity and Environment Network report concluded that the SCC in 2010 likely lies between $28 and $893 per ton, and will rise in 2050 to between $64 and $1,550 a ton.

MMN11 is Extremely Conservative

In short, the CO2 external costs estimated in MMN11 are extremely conservative. Nevertheless, they estimated that in the USA, coal combustion CO2 emissions cause an additional $15 billion in external damages per year which are not reflected in its market price. Had they used a more realistic SCC value, this figure would be much, much higher. This just reinforces our previous conclusion even further, that the economy would benefit by putting a price on CO2 emissions, thus allowing the free market to incorporate those (currently external) costs.

Arguments

Arguments

0

0  0

0 Assuming eternal growth is one of the reasons of the current mess, as was discussed here.

Alexandre:

You said " It's saying the goods this generation will enjoy have to be considered as more important than the goods the next generations will do "

And you are totally right.I do not know much about economics, so I was asking a bold question to see if someone else with more knowledge on the topic has arrived at the same thought than me, or if instead I had missed something.

I could not know much about economics, but I feel that something is completely wrong about how our society is described.I post this comment to see if others share the same feeling.

Assuming eternal growth is one of the reasons of the current mess, as was discussed here.

Alexandre:

You said " It's saying the goods this generation will enjoy have to be considered as more important than the goods the next generations will do "

And you are totally right.I do not know much about economics, so I was asking a bold question to see if someone else with more knowledge on the topic has arrived at the same thought than me, or if instead I had missed something.

I could not know much about economics, but I feel that something is completely wrong about how our society is described.I post this comment to see if others share the same feeling.

Comments