The Myth Debunking One-Pager

Posted on 20 March 2014 by John Cook

In late 2011, I co-authored the Debunking Handbook with Stephan Lewandowsky. The purpose of the handbook was to summarise all the psychological research into misinformation and debunking into a short, concise, practical guide. We published a much more comprehensive scholarly review afterwards. Nevertheless, the much shorter version has always been the preferred option.

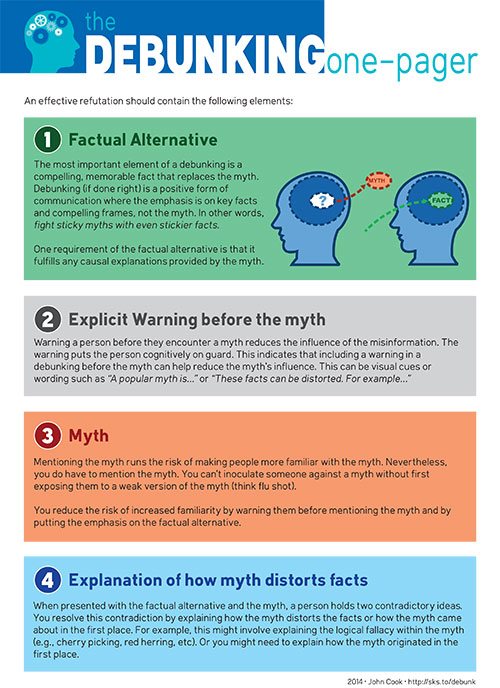

Until, perhaps, now. I was asked recently if I could boil down the key points of the Debunking Handbook into a one-pager. Apparently boiling down several decades of psychological research into six plain-English, graphics-heavy pages is too much in the age of Twitter :-)

As a result, here is the Debunking One-Pager:

An effective debunking is more about the fact than the myth

There are two major elements to an effective debunking. The most important thing when debunking a myth is identifying a compelling, memorable factual alternative to the myth. If you're debunking "the sun is causing global warming" and you're eliminating the sun as the cause, how do you communicate the alternative cause in a compelling manner? An effective debunking is more about the fact than the myth.

Nevertheless, you still need to mention the myth. In order for people to mentally label a myth as false, you need to first 'activate' it in their minds. Think of it like getting a flu shot. In order to inoculate yourself from a virus, you get exposed to a weaker version of the virus. This enables you to build up resistance when you encounter the real virus. Similarly, a debunking exposes the reader to a weaker version of the myth. That way, you inoculate people for when they encounter the misinformation.

This is why when communicating science, consider also explaining how the science might be distorted. Without that explanation, people might encounter misinformation down the track and have no way of reconciling the myth with the science. But if the science is accompanied with an explanation of how the myth distorts the science, then they can reconcile the contradiction. I recently presented my PhD research at the AGU Fall meeting, explaining how inoculating people against myths not only neutralizes the misinformation, it also discredits the source of the misinformation.

Oh and to pre-empt the wise-guy who asks for an even shorter version – a Debunking Tweet – I'll paraphrase from the Heath brothers:

Fight sticky myths with stickier facts.

Here is the Debunking One-Pager in PDF form. You can also access it via the short URL http://sks.to/debunkpage

Arguments

Arguments

Great work!

I find it best to start explaining the science and infer how people could mistake some section of the data but push home the facts that shows what the data is actually saying. Only then do i mention the myth and how they hide the true facts. My point is it might be best to not start with the myth but to give the information first to let them debunk the myth themselves

The Skeptical Science section "Most Used Climate Myths" seems to have some pretty strong versions of the myth being addressed, not weak, flu shot versions. Should these be changed in the light of this one pager when updates are made? All's fair ...

As an example the "Are surface temperatures reliable" myth contains the statement - "In fact, we found that 89 percent of the stations – nearly 9 of every 10 – fail to meet the National Weather Service’s own siting requirements that stations must be 30 meters (about 100 feet) or more away from an artificial heating or radiating/reflecting heat source." (Watts 2009)" This part of the myth wasn't addressed in the response as far as I could see. Nor does it seem that relevant to the important issues being discussed. But it does add weight to the myth with impressive stats.

Anyway I don't want to be critical of the fantastic work done here and the huge committment put into it. So please regard this as a constructive criticism.

I very much agree with @BC, in general and with regards the example. I would be happy to volunteer to help reword if a team effort is required, although I'd need to use the science presented to help do the job rather than my own knowledge, which is not as rounded as other posters here.

On a related note, I have come to realise that a lot of the information provided by e.g. Watts is or appears very detailed, and is not completely dealt with by rebuttals. At a higher level of detail, logic says to me that the Watts arguments must be flawed, but the information to debunk them completely is not immediately apparent. A good example is the one presented by @BC above.

Michael Whittemore is correct. If you start with your opponent's frame, no matter how you want to precondition it, you reinforce it. To avoid doing so, state your position, and then you can point out what an ass the other side is (or words to that effect). A very good read on this phenomenon is George Lakoff's book, "Don't Think of an Elephant."