Drought and Deforestation in Brazil

Posted on 4 December 2014 by Guest Author

This is a guest post by Alexandre Lacerda who lives in Serra Negra, a small town about 150 Km north of São Paulo city, Brazil, where he works as an attorney and entrepreneur. He has contributed many of the Portuguese translations of Skeptical Science arguments and this is his first blog post.

I live in São Paulo, the richest state in Brazil, and also the one with the largest population. I live in a small town up on the hills about 150 Km north of São Paulo city, a large city with some 20 million inhabitants if you include all its surrounding metropolitan area.

The climate here is quite pleasant: dry, mild winters in the middle of the year (remember, this is the southern hemisphere) when we get a few frosts and hot summers cooled by frequent torrential rain in December-January. Well, at least that’s how it used to be. Frosts became a rare event, when they happen at all. And summer rains failed last year, which is what this article is about.

In our small town, public water reservoirs usually get quite low during winter, and get filled up again every summer with reliable rainfall. That’s something we learned to count on almost as we count on the sun rising tomorrow. The low reservoirs were something we looked at as something normal for the season, just as you don’t usually panic when your fridge is empty: after all, it will be replenished when needed.

Then, after a pretty unremarkable December last year, with a few good showers, January came and it was sunny. Day after day, we enjoyed the summer vacation with the feeling that the fun sunny days would any time be over. But they lingered on all month, then the next month, then the month after that. It slowly dawned on us that the rainy season would be over, but the necessary rain would not come.

Local reservoir in normal condition (on top) and at the present drought (above). (personal archive)

Of course, meanwhile, reservoirs ran low. Actually, for the first time in my lifetime, they were extremely low in January, when they should be overflowing with brownish water.

We hoped for the odd off-season rain during the year to keep reservoirs from going empty. Our small town was just lucky enough to get barely the rainfall it needed. São Paulo city, on the other hand, is too large to have its problems solved with the occasional rain, so its main reservoir, Cantareira (actually an array of five interconnected dams), kept going lower. Today it is only at 9% of its capacity.

I know politicians elsewhere in the world are selfless and reliable administrators, but here they all (state and federal government) were busy crafting creative marketing strategies to convince the public that the real culprit was the other party. Heck, it was an election year.

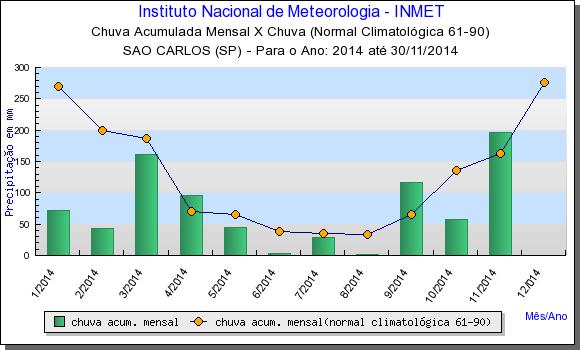

Everyone hoped we just had to sit tight through the year to be saved by next summer’s rain. Well, it should have started raining again by September or October in a normal year. However, October was the driest since 1985.

Fig. 1: Monthly precipitation (green) and the climatic normal (yellow) in a nearby town. (source: INMET)

Capybaras in a local reservoir. It should be full in November. (personal archive)

People here understand that this situation can get critical; much more serious than it is already. We are used to abundant, cheap water. Many people hose their sidewalks with water instead of sweeping it, and just keep the water running from the tap all the time while washing dishes. We shower at least once a day, some do it for a very long time, and it’s a serious social blunder to even suggest you skipped just one day on your daily duty of showering. I’m just mentioning it to illustrate what kind of world we’re used to living in, and how a world of water scarcity would force us to make huge adjustments in our daily lives.

The Science

Aside from the political solution from blaming each other, people do expect some effective solution for this kind of problem.

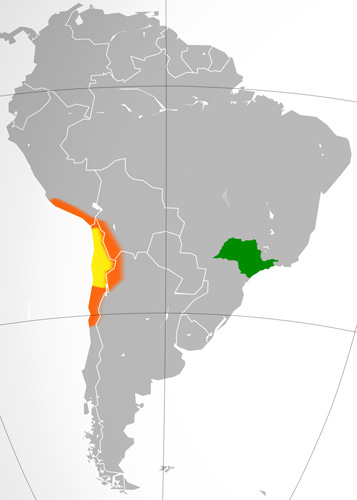

Fig. 2: Relative locations of the Atacama desert (yellow) and the Brazilian state of São Paulo (green). (Source: Wikipedia)

In 2007, Sampaio et al. published a paper called “Regional climate change over eastern Amazonia caused by pasture and soybean cropland expansion”. It suggested there’s a tipping point in the capability of the Amazon rainforest to recycle water inland. Let’s explain this: water comes to the Amazon from the Atlantic Ocean only until it rains down for the first time. From then on, it’s the forest itself that promotes transpiration, producing new clouds that go a bit further inland, repeating the cycle many times and so making rain come to many parts of the continent where it wouldn’t otherwise. São Paulo, for instance, is on the same latitude of the Chilean Atacama desert (Fig. 4), and is roughly on the descending end of the southern Hadley cell. Therefore, it should be very dry, were it not for other climatic factors that offset this, such as the capacity of equatorial forests to recycle their water inland through transpiration. This moisture is then carried southwards through a low level jet, east of the Andes (Marengo et al. 2007). Thanks to this, our state has a lush, tropical rainforest with much biodiversity.

This is more like it. A two-day hike in the coastal tropical forest of São Paulo. (personal archive)

The tipping point Sampaio and his colleagues modeled suggested that once 40% of the Amazon was deforested this natural water pump would be broken and the so-called “aerial rivers” would stop flowing.

Today, 14% of the Amazon is already clear-cut. Another 22% is degraded (selectively cut to different extents). That adds up to 36%, pretty close to the calculated tipping point. Even if we consider the unavoidable uncertainties (which we know can cut both ways), the agreement between prediction and observation is worth serious attention.

Let’s not forget that the Amazon also had two “once-in-a-century” droughts, in 2005 and 2010. The second one was especially severe in the West-southwest part of the Amazon – that is, the region farthest from the ocean, and most dependent on the recycling process.

The Bottom Line

It is one thing to think of climate change as an abstract idea, it is another thing to see it with your own eyes and then – only then – really ponder about the consequences. Societies are formed to make the best use of existing resources – including the climate. Less rain means losses and suffering to people, not to mention drastic ecological consequences. I don’t imagine that more rain would be of much use either. It’s not that we had the ideal amount: we just built our cities and farms to match the existing climate. Changing everything would be costly, both in an economic and a human way.

We know the climate is a chaotic system, and changes may not come gradually. We still don’t have data to claim with certainty that this is a sample of what’s coming. Nor do we know with certainty what causes to attribute this to: it may be the deforestation, maybe global climate change, or something else. However, when you start messing with a chaotic system like this, you can expect the unexpected.

It’s just not wise to mess with something as important as this if we don’t fully know how it works and how it will behave. The same study recomends not only a total halt on deforestation, but also an urgent effort in reforestation. I do hope policymakers listen to this.

References:

Driest October in 20 years: http://g1.globo.com/jornal-hoje/noticia/2014/10/mes-de-outubro-termina-como-o-mais-seco-dos-ultimos-20-anos-em-sp.html

INMET: http://www.inmet.gov.br/

PDF - Futuro Climático da Amazônia (review report, in Portuguese): http://www.ccst.inpe.br/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/Futuro-Climatico-da-Amazonia.pdf

Press article about the review report above (in Portuguese):

Novo estudo liga desmatamento da Amazônia a seca no país: http://g1.globo.com/natureza/noticia/2014/10/novo-estudo-liga-desmatamento-da-amazonia-seca-no-pais.html

PDF - Sampaio et al. 2007, Regional climate change over eastern Amazonia caused by pasture and soybean cropland expansion, Geophysical Research Letters, vol. 34. http://www.csr.ufmg.br/~britaldo/Gilvan.pdf

PDF - Marengo et al. 2004, Climatology of the Low-Level Jet East of the Andes as Derived from the NCEP–NCAR Reanalyses: Characteristics and Temporal Variability, Journal of Climate, vol. 17 no. 12. http://journals.ametsoc.org/doi/pdf/10.1175/1520-0442%282004%29017%3C2261%3ACOTLJE%3E2.0.CO%3B2

Arguments

Arguments

Thanks for covering this important story in such a thoughtful, big-picture way. If only we saw more coverage like this from other, more main stream, media!

I sure hope that deforestation in Brazil will finally stop. If the deforestation really is contributing to draughts (which I think is likely), Brazil people will have to learn the hard way that reforestation is easier said than done.

Thanks, Alexandre and vonMackwitz. Do either of you (or anyone else) have a clear idea what the main reasons for deforestation are in that particular region?

vonMackwitz @3,

Unfortunately this recent BBC article indicates that what you hope for is not as likely as it needs to be.

wili at 13:43 PM on 5 December, 2014

The data I have about that are not very recent (one paper from 2009 and another from 2003, both in Portuguese), but I don't think this has changed much in the meantime. It's mainly cattle ranching (more than half), and agriculture to a lesser extent, especially soybean plantation.

It's interesting and sad to notice that logging is a very minor activity comparing to those. Often the deforestation process is done with tractors simply pulling the trees out and discarding the wood. Logging is not a first step to other activities, either.

Deforestation for ranching, plantations and farming is also a major reason for the reduction of Indonesia's rain forests.

And in many nations the ranching, plantations, and farming is not done for 'internal consumption'. In many cases it is done for international trade. In some cases less fortunate nations are fooled into accepting 'development' loans to build massive infrastructure that is promised to bring them 'properity'. And the infrastructure is specifically focused on international trade, it is not hospitals and schools. All that it brings them is insurmountable debt and a desperate desire to expand their production of basic commodities for international trade. And their expansion of that activity reduces global prices for commodities reducing the benefit they get, all while their debt payments grow.

Thanks again for the info. Pretty much what I though. I imagine that most of the soybeans also go toward cattle feed. So pretty much our burger habit is obliterating the most populous area on this half of the planet...nice.

Meanwhile, as they scrape ever further toward the bottom of the barrel, water quality is getting noticably worse, and it's likely causing long-term damage to infrastructure: translate.google.com/translate?hl=en&sl=pt&u=http://noticias.portalvox.com/sao-paulo/2014/12/sabesp-registra-82-de-volume-de-agua-sistema-cantareira.html&prev=search