Hockey sticks to huge methane burps: Five papers that shaped climate science in 2013

Posted on 3 January 2014 by dana1981

This is a re-post from The Carbon Brief by Roz Pidcock

There's no doubt, 2013 was a busy year in climate science. As well as a bumper new climate report from the UN's official climate assessment body - the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) - a few bits of research caused quite a stir on their own.

We've cast our collective Carbon Brief mind back over the year to find the five science papers that had everybody talking.

1. What hockey stick graphs tell us about recent climate change

Using fossils, corals, ice cores and tree rings, a study in the journal Science in March became the first to take a 11,300-year peek back into earth's temperature history.

Shaun Marcott and colleagues showed global temperature rose faster in the past century than it has since the end of the last ice age, more than 11,000 years ago.

The story piqued the interest of The Times, The Independent, The Daily Mail and The Evening Standard. And as an extension of Michael Mann's iconic "hockey stick" graph, the paper attracted a good deal of attention from climate skeptic corners too.

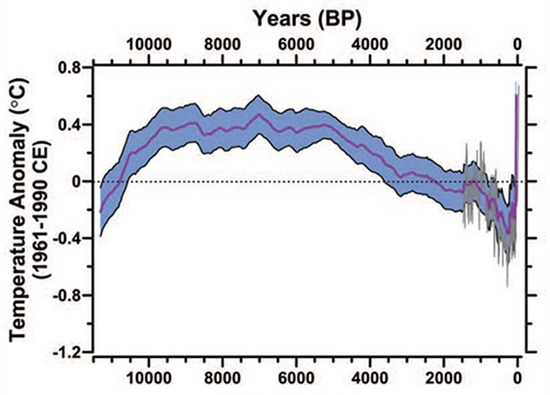

Global temperature reconstructed for the past 11,300 years by Marcott et al. (purple line) and for the past 2,000 years by Mann et al. (grey lines) Source: Skeptical Science

Marcott, S. A. et al., (2013) A Reconstruction of Regional and Global Temperature for the Past 11,300 Years. Science, DOI:10.1126/science.1228026

2.World's oceans are getting warmer, faster

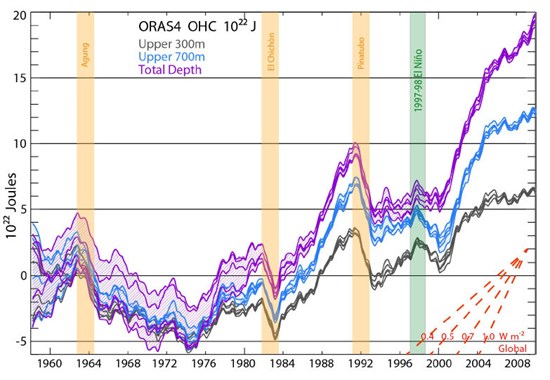

A study led by UK researcher Magdalena Balmaseda highlighted why its important not to overlook the oceans when thinking about climate change.

Publishing in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, the authors showed just how much the oceans have warmed in the past 50 years - and that the pace accelerated sharply after about 2000.

The data suggests heat is finding its way to the deep ocean, rather than staying in the upper layer. That could be one reason for less surface warming in the last 15 years than in previous decades, suggested the authors. Lead author Kevin Trenberth told Carbon Brief:

"[The new study] means that the current hiatus in surface warming is transient and global warming has not gone away."

Amount of heat stored in the whole ocean in past five decades (purple), the top 700 m (blue) and just the top 300 m (grey). Source: Balmaseda et al., ( 2013)

The paper just missed the deadline for consideration in the recent IPCC report. But as a potential explanation for the so-called surface warming slowdown, the oceans still got a fair bit of media attention when the report finally came out in September.

Balmaseda, M. A., Trenberth, K. E. & Källén, E. (2013) Distinctive climate signals in reanalysis of global ocean heat content. Geophysical Research Letters, DOI:10/1002/grl.50382

3. Surface warming slowdown doesn't affect climate sensitivity, study says

This was the year climate sensitivity became a thing. The degree of earth's sensitivity to greenhouse gases is key to understanding climate change. This year, a particularly technical way to measure it made the leap from the quiet corridors of scientific institutes to the mainstream media.

The Economist brought the issue to the masses in April by suggesting slower than expected warming in recent years meant scientists were rethinking how sensitive the climate is.

But it was a case of mistranslation by the Economist and a paper by Alexander Otto a month later put paid to the idea. Climate sensitivity is pretty nuanced stuff, but the paper's gist was that recent sluggish surface temperatures have no bearing on the warming we can expect in the long term.

The authors' climate sensitivity estimate sat just below the likely range put forward by the IPCC. While not a conclusive argument for shifting the range altogether, Otto told us it might support lowering the bottom boundary a bit - and this is what happened when the IPCC released its report.

The authors' prediction for the next few decades caused a bit of a stir too. The prospect of less warming than previously thought - because heat is temporarily entering the oceans - prompted some commentators to jump to the conclusion that climate change no longer poses a problem.

Otto, A. et al., (2013) Energy budget constraints on climate response. Nature Geoscience, DOI:10.1038/ngeo1836

4. How likely is a huge Arctic methane pulse? We find disagreement among scientists

Rising temperatures in the Arctic could see 50 billion tonnes of methane currently frozen in the seabed released into the atmosphere over ten years, a Nature comment piece argued in July.

The paper's topline figure pricked the media's ears - that the climate change consequences of that amount of methane could cost a whopping $60 trillion.

Expressing the result of huge and sudden methane release as an economic cost is a new concept. But the study's novelty was eclipsed by scientists' criticisms that a 50 billion tonne pulse was "totally unjustified". Professor David Archer from the University of Chicago told Carbon Brief:

"No one has proposed any mechanism for releasing methane that wouldn't take centuries, not just a few years."

Dr Nafeez Ahmed, whose blog for the Guardian reported the research, later conceded the perils of attaching too much weight to one study, saying he hadn't realised the scenario was "speculative".

Whiteman, G., Hope, C. & Wadhams, P. (2013) Climate science: Vast costs of Arctic change. Nature Climate Change, DOI:10.1038/499401a

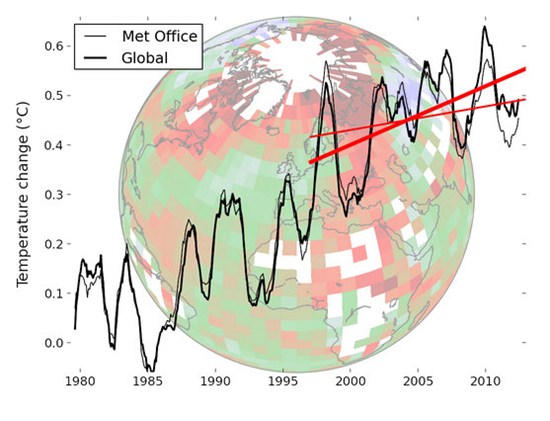

The so-called surface warming slowdown - and what may be driving it - has been quite a media preoccupation in the past year - particularly in the run up to the IPCC report launch in September.

Research earlier in the year suggested natural cycles could be squirrelling heat away into the deep ocean. Cuts in CFCs under the Montreal Protocol could be contributing too, scientists suggested.

But a paper published in November shed new light on this much-discussed topic, suggesting temperature rise in the last decade and a half may be nothing unusual after all.

The authors said plugging well-known gaps in one of the major global datasets - particularly in the Arctic - brings the rate of warming since 1997 much more in line with previous decades.

Warming after 1997 in the original temperature data (thin red line) compared to the updated data (thick red line). Source: Cowtan & Way (2013)

Coming on the heels of a year of heated speculation, the paper met with plenty of interest from climate scientists and skeptics alike.

So where does it leave the slowdown? This RealClimate blog does a good job of explaining how different explanations for slower warming fit together. The gist is there is still evidence for a slowdown, but the magnitude may not be as great as previously thought.

This won't be the last word on the slowdown, warn the authors. Lead author Kevin Cowtan had another salient point to make, looking at short time periods "has dominated the public discourse but is in our view a misleading approach to evaluating climate science."

Cowtan, K. & Way, R.G. (2013) Coverage bias in the HadCRUT4 temperature series and its impact on recent temperature trends. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, DOI: 10.1002/qj.2297

Arguments

Arguments

Whilst these were all significant and interesting papers it seems a stretch to say that they were the five papers that 'shaped climate science' last year. I can imagine certain 'sceptics' selecting their own set of five papers to tell an entirely different story.

Really? And which peer-reviewed papers would these be that tell an entirely different story?

"Skeptics" don't cite a lot of papers.

As for these being the top 5, I would say that 1, 2 and 5 are well chosen. 3 and 4 were more media sensations than major contributions to climatology.

The author has missed the latesat paper by Steven Sherwood from NSW uni, quantifying the cloud formation changes from H2O forcing:

Planet likely to warm by 4C by 2100, scientists warn

video

Several SkS commenters quoted that paper lately.

That late 2013 paper, has not "shaped climate science" yet, but it certainly will. It should put to bed the Lindzen's "negative cloud feadback". Then, I predict, it will cause IPCC to revise upwards their ECS.

Chriskoz,

While the paper you linked is very interesting, the original article in Nature is dated January 2. If the results hold up it might be one of the five top articles for 2014.

Well, Cowtan and Way will also be listed as 2014 when it hits the print edition.

While the attention is very flattering, in scientific terms our paper is really only addressing a technical data analysis issue. If climate change skeptics had not managed to inflate the short term trend into the "most pressing" issue in climate science (according to BBC Newsnight) then it would not have attracted much interest. That's not to say that it didn't need doing, but as the Stoat said, "anyone could have done it".

In my view the real scientific breakthrough missing from this list is Kosaka and Xie.

Kevin

Cowtan and Way is a very nice paper. I do wish I had written it; but it is not fair to say "anyone could have done it" a good grounding in physical sciences is needed. I know in much of my professional life everyone has a PhD in Physics - but this is not generally true. When I discuss climate change with my brother in law (who is a skeptic) we have no common ground. Much of the population has very little grounding in Physical Sciences. Well done again

sean

Interesting discussion, thanks. I'd say my idea was to summarise papers that made it into the media's collective consciousness this year rather than perhaps the most worthy contributions to climate science - although some tick both boxes. I suppose a better title might have been "5 papers that shaped climate science discourse'.

Kosaka & Xie nearly made the cut (and I do link to it in the final section) since the pre-WG1 timing made it quite a media conversation piece. But I felt Balmaseda et al. first described the Pacific warming/cooling mechanism (incidentally, the authors of that paper had some interesting comments about Kosaka & Xie on that front http://bit.ly/1g7Ocm6)

And yes, sadly the new Sherwood paper about climate sensitivity came just after I'd written this piece. Though it perhaps would have slotted in as a continuation of the media interest in climate sensitivity this year rather than forming a category on its own. Glad to hear all your thoughts, keep them coming ...

We all have our own personal vectors of importance weights when it comes to climate research. These days mine tend to place much weight on research that sheds a clearer light on why we shouldn’t be considering solar radiation management geo-engineering, what I’ve called ‘the mother of all moral hazards’. And so the two papers that I would rate as highly policy relevant this past year are the theoretical paper by A. Kleidon and M. Renner of the Max Planck Institute published in Earth Systems Dynamics (“A simple explanation for the sensitivity of the hydrologic cycle to surface temperature and solar radiation and its implications for global climate change”) and then the multiple Earth System climate-model verification of this effect by S. Tilmes et al. in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Atmospheres (“The hydrological impact of geoengineering in the Geoengineering Model Intercomparison Project”). Together, they make a compelling case that if you tried to nullify global temperature increases with solar radiation management techniques, the expected consequences would be reduced global evaporation leading to lower rainfall and significant changes in its distribution.

There is a mechanism that could result in a sudden methane burp. As a thougt experiment, take a diving bottle and fill it half full of clathrate that you have dredged from the ocean. Put a bung in the opening. Deck temperature is, say 50C. The clathrate begins to give up its methane and the pressure rises in the bottle. When the pressure gets to a certain point (equivalent to a depth of about 700m) the clatrate stops giving out its methane. If clatrate below the bottom of the ocean is being stabilized by, for instance, the strength of an overlying layer of permafrost rather than by the depth at which it occurs. anything that breaches this cap (mehanaclude - like an aquaclude) could result in a sudden release of methane that is already in the gasseous form and from remaining clathrate that is now exposed to warm water but now without sufficient pressure to keep it stable. An earthquake could do it or a land slide on the contenental slope north of Russia as the permafrost slowly weakens to the point where such a land slide can occur.

http://mtkass.blogspot.co.nz/2013/08/a-methane-spike.html

Maybe I've spent too much time in the wrong places to judge the real nature of the climate science discourse (it certainly feels that way) but I'd have said Nic Lewis' climate sensitivity paper probably had a disproportionately large impact. Did this paper get on to the short list Roz?

OPatrick @11, creating a buzz in the denialosphere is not the same as having a significant scientific impact. As to the later, Nic Lewis's paper is just one recent paper on climate sensitivity, many of which show much larger values:

There is no particular reason to think his method is more reliable than others, and indeed, some reason to think its results vary widely depending on choice of time frame, making it a fairly unreliable method.

Tom, I agree - and, as you've said, similar can be said for the Sherwood paper and indeed probably for any of the papers listed above. Any single paper is only ever likely to be an incremental improvement in our understanding.

industrialization ended the little ice age

the next one would probably be a recent analysis by JPL regarding the little ice age:

skeptics are forever saying that the recent warming is caused by "coming out of the little ice age" without causation. If industrialization is the cause of "coming out of the little ice age" and industrialization is the primary force that increases atmospheric CO2 then, in this case, I am in full agreement with those "skeptics".

jja, as the top graph shows, global temperatures had been dropping by about .1 degree C per millennium for the last 7000 years (since the 'Holocene Climate Optimum'). The Little Ice Age was just a little, probably regional, wiggle in that long decline.

So beyond your excellent point about industrialization bringing us out of that cold trend, we should point out that we should be some part of tenth of a degree _colder_ than that period by now. That we are instead some .8 degrees warmer, in that context, is even more shocking.

The importance of the first graph is not just that it shows that the temps are rising faster than any other time in the holocene, but that we are now hotter than any time in the Holocene, which in turn means that we are hotter than any time in the last 110,000 years or so (since the Eemian Interglacial)--in other words hotter than any time since fully modern man evolved.

We have already created a world that our species has never experienced, and every day we are pushing it further outside of the range underwhich we have evolved as a species and as a civilization. So thanks for placing that important graph at the top. It should be at the top of every human's mind.

Slight correction: In spite of what the graph seems to show, the last part of the abstract of the paper states specifically:

"Current global temperatures of the past decade have not yet exceeded peak interglacial values but are warmer than during ~75% of the Holocene temperature history. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change model projections for 2100 exceed the full distribution of Holocene temperature under all plausible greenhouse gas emission scenarios."

So we are now warmer than nearly any time in the Holocene, and getting warmer fast.

Not trying to be make any waves but wasn't there a big dust-up at the time of publication regarding statements similar to the following (quoted from above):

And the actual language in the paper that was expanded upon in the FAQ at realclimate.org (my emphasis):

In my mind, that's a pretty clear contradiction. Maybe others disagree?

If not, I think we should offer proper caveats about the results of the study rather than open ourselves up to such easy criticisms.

Just my $.02.

P.S. I know that Tamino made a blog post defending those types of claims so maybe reference that as well even though it was neither peer-reviewed nor included in the Marcott analysis.

Hank_Stoney - Regarding Marcott et al 2013, Tamino tested a theoretic 0.9 spike (100 years up, 100 years down) against their Monte Carlo testing, and found they were clearly visible in the resulting analysis. I personally repeated that with a separate technique, using the frequency transform Marcott et al described in their supplemental data, and found that such a spike would leave a 0.2-0.3C spike in the final data.

No such spike appears anywhere in the Holocene data Marcott et al analyzed. And that doesn't even include the physics indicating a CO2-driven spike of the kind we are currently experiencing cannot just vanish over 100 years - rather, 1-10Ky would be required (Archer et al 2008); there is just no physical mechanism for such a spike.

The entire 'dust-up' you mention arose from fantasy hypotheticals created by 'skeptics', hypotheticals which simply do not hold up under analysis. Hypotheticals, I'll note, which are certainly not peer-reviewed...

KR @19, as I contributed in a small way to the 'dust-up', I should probably feel insulted that you have included me among the 'skeptics'. As I have noted elsewhere, neither Tamino nor your tests allow for the innate smoothing implicit in any reconstruction from the fact that the measured age of each proxy will differ from the actual age of the proxy by some random amount. I have discussed this in detail here, where interested readers can find your response, and my response to your response. My argument was, of course, not that the Marcott et al algorithm would not show rapid changes in temperature occuring over a short period, but that neither you nor Tamino had shown that it would.

Tom Curtis - I strongly disagree, and have responded in detail on the appropriate thread.

@KR - Fair enough but then why did Marcott et al not explicitly state this? Even after having been given the opportunity to respond to this issue in the FAQ, they chosenot to make such a claim. Given the significance of such a result, I'd like to think they would have made their case if it were at all justified.

So I reiterate: in order to avoid confusion when discussing this (or any other) study, I personally think that it would be wise to carefully distinguish between the actual peer-reviewed conclusions that the authors intended and those inferred and written about in the blogosphere after the fact by those such as Tamino and yourself, in this instance.

In any case, the Marcott et al paper was a great contribution to paleoclimate studies from last year and certainly deserves mention in this post.

Hank_Stoney - I suspect because, in part, there is considerable confusion between resolution and detection - a confusion I have encountered more than once in the realm of signal processing.

A band-limit of 300 years, as per the Marcott et al analysis, means that their methodology won't be able to resolve or separate discrete events (warming or cooling) less than perhaps 600 years apart, as they would be blurred together. Detecting that something happened, however, is another story entirely. You can look through a telescope at a distant pulsar or supernova, sized far below the resolution of your telescope - and yet detect it as a bright spot that clearly tells you that something is present. In much the same fashion the 'unicorn spike' so beloved of the 'skeptics' would add 0.9*100 or 90 Cyr to the Marcott data, and even the blurring of the Marcott processing would still show this as a clearly detectable bump in the mean.

You don't need to resolve something to detect it.

I agree, it's important to distinguish between peer-reviewed science and unfiltered (so to speak) opinions on blogs. Which is but one reason I found your description of the blog based discussion of 'unicorns' as a dust-up a bit odd; that seems to be giving more credence to blogged objections than to the replies.