Great Barrier Reef Part 1: Current Conditions and Human Impacts

Posted on 3 July 2011 by Ove Hoegh-Guldberg

In a recent article published in Quadrant magazine, Bob Carter claimed that "the Great Barrier Reef is in fine fettle." Skeptical of this statement, we contacted Dr. Ove Hoegh-Guldberg, Professor of Marine Studies and Director of the Global Change Institute at the University of Queensland, one of the foremost experts on the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), and asked him to evaluate Carter's claim and other frequent questions about the GBR. This is the first in a three part series from Dr. Hoegh-Guldberg on the state of the GBR.

What's the current state of the GBR (i.e. is it really "in fine fettle")?

Despite being one of the best managed marine ecosystems worldwide, there is evidence that the ecological 'health' of the Great Barrier Reef has declined since the arrival of European settlers into the Queensland region. This evidence comes from a number of key sources. This area is not without its controversy, which is discussed elsewhere at Skeptical Science by Professor John Bruno (University of North Carolina) and others.

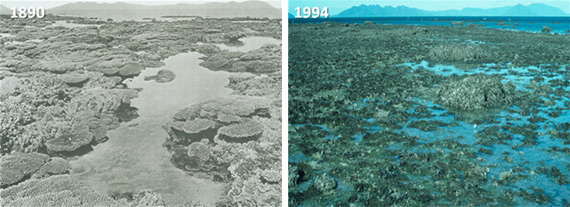

Historic photographic analysis (> late 19th century)

One of the first and most direct way has been via 'before and after' photographs assembled by Dr. David Wachenfeld of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. Dr. Wachenfeld searched photographic archives of pictures of intertidal coral reef systems going back over 100 years. He then organised photographs to be taken in exactly the same spot of the same reef systems. The results revealed no change in reefs systems at 6 out of the 14 sites where it was possible to compare photographs from 100 or more years ago. At four sites, there was evidence of change in the health of intertidal reef communities, while at the 4 remaining sites, coral had more or less disappeared from the intertidal reef areas (Wachenfeld 1997). Photographic analysis is a very direct way of assessing whether or not coral reefs have declined at particular locations. However, it is important to acknowledge that photographers probably went out to photograph 'beautiful' areas of the reef as opposed to areas without coral cover. The criticism that arises is that had that happen, we might have seen an equal and opposite set of photographs in which coral returns to coastal reef flats. Several more recent studies have been exploring sediments using push coring and radioisotope dating techniques, which is allowing a reconstruction of past communities based on the sediments that have built-up. These studies are revealing that major changes have been occurring in coastal coral communities, with the general trend that coral communities have converted into seaweed communities that are very different to the coral communities of old.

Figure 1. Matched photographs of the same section of reef taken around 1890 by William Saville- Kent and again in 1994 by Andrew Elliott. Full details can be obtained in the study reported by Wachenfeld (1997).

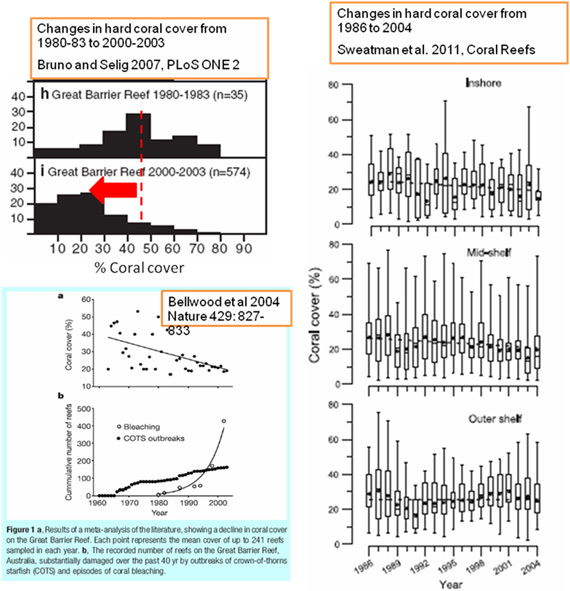

Meta-studies: long-term trends (> 1960)

Several research groups have assembled datasets from the growing number of studies that have been undertaken on the Great Barrier Reef. These studies are referred to as meta-studies given that they depend on drawing numbers from published papers. The idea is that if these sources are carefully vetted for a certain level of quality and rigor, then the dataset of numbers on things like the abundance of coral on coral reefs at a certain time in recent history can be established. One of the first of these was (Bellwood et al. 2004) who found a strong negative trend in coral abundance on Great Barrier Reef sites going back to 1960. This analysis supported a related study by (Pandolfi et al. 2003) who used historic and paleontological evidence to compare the Great Barrier Reef to other reef systems worldwide. They also concluded that the Great Barrier Reef, although still a beautiful reef system had declined over the past century. The third study by (Bruno and Selig 2007) undertook a similar analysis, and compared coral cover on the Great Barrier Reef in the early 1980s to recent survey data. This study revealed a major drop in coral cover (40-50%).

Figure 2. Three independent studies reporting changes in the percentage of coral cover on reefs within the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park.

AIMS long-term ecological surveys (>1986)

The third category of information comes from long-term survey data. The Australian Institute of Marine Science began annual ecological survey of key aspects of coral and fish abundance on the Great Barrier Reef in 1986. While these surveys biased toward offshore reef areas and hence have probably not caught the full picture of human impacts on the Great Barrier Reef, they are empirically sound in terms of the methodology needed to examine ecological parameters such as coral abundance over time. As indicated above, there has been some scientific debate (which always goes on and is part of the sceptical process of science) and some of the details have been discussed by Professor John Bruno in separate postings to SkS and Climate Shifts.

Drawing together these three types of studies, there is fairly compelling evidence that the Great Barrier Reef has undergone significant ecological change over the past 50 to 100 years. Even the declined reported by the AIMS Long-Term Monitoring Project (Figure 2) from 28% to 22% coral cover (a decrease of 22%) from 1986 to 2004 (Sweatman et al. 2011) is of great concern given the massive size of the Great Barrier Reef and the speed of this change (10% decrease per decade).

How do we know the GBR decline is due to human impacts?

Evidence for humans being responsible for the recent changes in the Great Barrier Reef comes from a number of different disciplines and sources.

Firstly, there is a considerable body of information within the literature that has examined the sensitivity of reef building corals, a core component of coral reefs, to stressors such as high temperatures and light levels, reduced salinity and alkalinity, elevated nutrient loads, sedimentation, toxins, and pollutants. This information has been assembled in a number of different review articles and can be accessed through scientific journals such as Coral Reefs. The peer-reviewed science in these journal articles deal with the core sensitivity of reef building corals to particular factors.

Secondly, there is abundant field evidence of these types of factors having a big impact on reef ecosystems. In this regard, there are numerous examples of sudden changes to environmental parameters (e.g. flood damage through reduced salinity to restructures, mass coral bleaching events triggered by elevated sea temperatures) which are consistent with the information from more laboratory and aquarium-based studies. Taken together, the two are constantly interacting. Observations in the laboratory that are not supported by field evidence generally trigger reinvestigation in the laboratory, and vice verse.

Lastly, there are modelling studies which summarise our understanding of how coral reefs might react to changes in the physical, chemical, and biological changes within the environment. These studies have provided projections or predictions which can be tested. In cases where a projection or prediction fails to be supported by laboratory and field evidence, models are then re-examined and reconfigured. The most important step, however, is to ensure that models that have been reconfigured are subsequently tested. Without this final step, one can fall into the trap of models that are adjusted to fit the results as opposed to being truly predictive in nature.

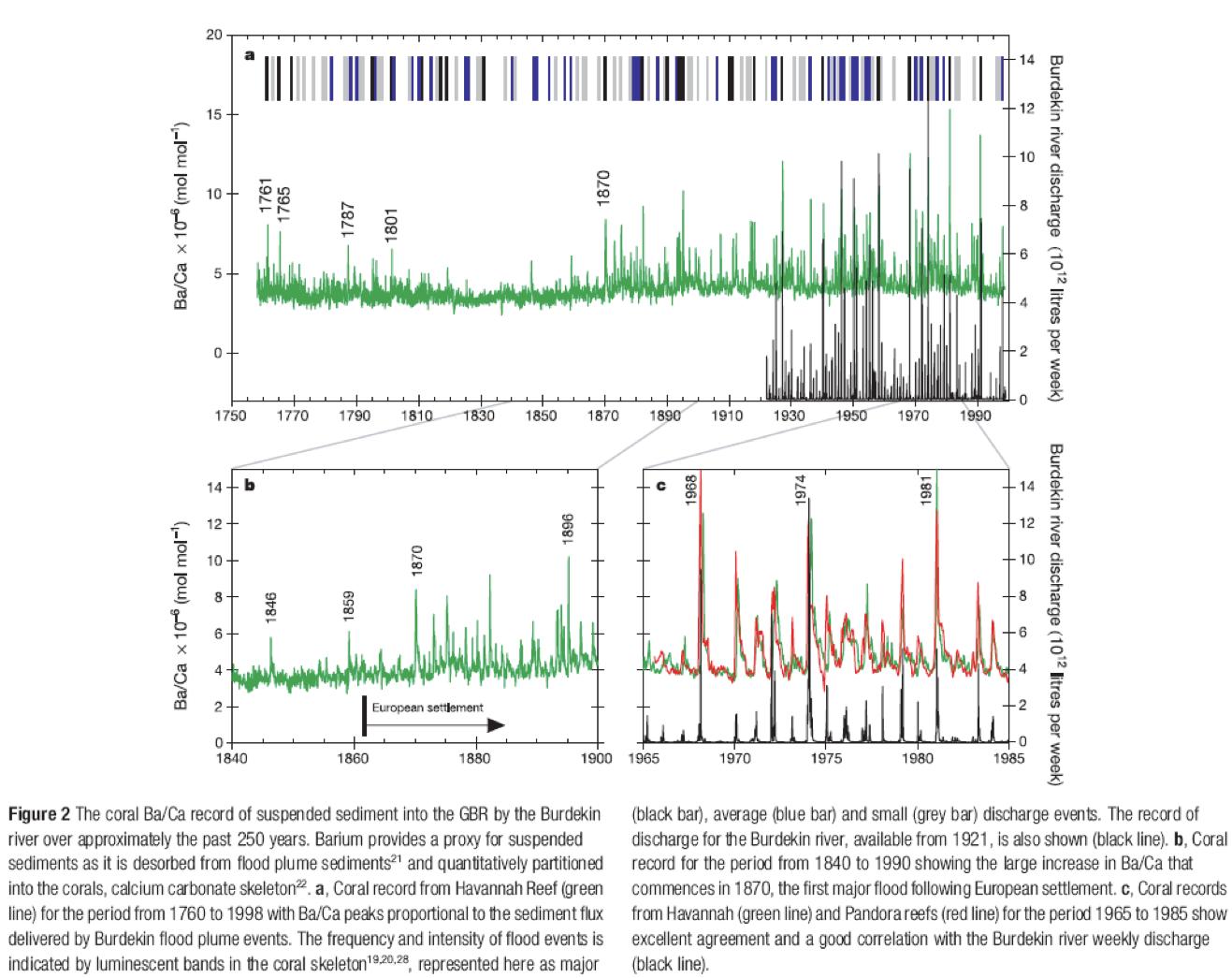

With these datasets in place, how are we able to link human activities to the changes that we are seeing? This comes down to the link between the stressors (elevated temperatures and light levels, reduce salinity and alkalinity, elevated nutrient loads, sedimentation, toxins and pollutants) and human activities. At local levels, there are extremely strong links between changes to land-use along the Queensland coast and elevated levels of sediments, nutrients, toxins and pollutants, and low salinity events. As trees were cut down in the major river catchments, for example, soil was destabilised along the banks of the rivers and creeks that feed into the coastal areas of the Great Barrier Reef. This led to much higher levels of these known stressors. Interestingly, there have been some studies (McCulloch et al. 2003) that have used isotopic information to show that the levels of these stressors have increased by 5-10 fold since the modification by European farmers of river catchments within the Great Barrier Reef basin.

From McCulloch et al. (2003)

These types of data have built up a comprehensive set of linkages between human activities such as deforestation, intensive agriculture, and fishing. There are a number of resources that are available at the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority and at the Australian Research Council Centre for Excellence in Coral Reef Studies and explore the evidence and background to our concern about these local factors.

In Part 2 of this series, Dr. Hoegh-Guldberg will evaluate whether climate change poses a threat to the GBR.

References

Bellwood, D. R., T. P. Hughes, C. Folke, and M. Nyström, 2004: Confronting the coral reef crisis. Nature, 429, 827-833.

Bruno, J. F., and E. R. Selig, 2007: Regional decline of coral cover in the Indo-Pacific: timing, extent, and subregional comparisons. PLoS ONE. , 2, e711.

McCulloch, M., S. Fallon, T. Wyndham, E. Hendy, J. Lough, and D. Barnes, 2003: Coral record of increased sediment flux to the inner Great Barrier Reef since European settlement. Nature, 421, 727-730.

Pandolfi, J. M., and Coauthors, 2003: Global trajectories of the long-term decline of coral reef ecosystems. Science, 301, 955.

Wachenfeld, D., 1997: Long-term trends in the status of coral reef-flat benthos-The use of historical photographs. 134-148.

Arguments

Arguments

0

0  0

0 If that trend continues through to September/October 2011 we will have another bleaching event in the Caribbean. Not a rosy future for coral sadly.

If that trend continues through to September/October 2011 we will have another bleaching event in the Caribbean. Not a rosy future for coral sadly.

Comments