Naïve empiricism and what theory suggests about errors in observed global warming

Posted on 23 August 2016 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Variable Variability

In its time it was huge progress that Francis Bacon stressed the importance of observations. Even if he did not do that much science himself, his advocacy for the Baconian (scientific) method, gave him a place as one of the fathers of modern science together with Nicolaus Copernicus and Isaac Newton.

However, you can also become too fundamentalist about empiricism. Modern science is characterized by an intricate interplay of observations and theory. An observation is never free of theory. You may not be aware of it, but you make theoretical assumptions about what you see in any observation. Theory also guides what to observe, what kind of experiments to make.

Charles Darwin often claimed to adhere to Bacon's ideals, but he had another side. University of California professor of biology and philosophy Francisco Ayala writes in Darwin and the scientific method:

“Let theory guide your observations.” Indeed, Darwin had no use for the empiricist claim that a scientist should not have a preconception or hypothesis that would guide his work. Otherwise, as he wrote, one “might as well go into a gravel pit and count the pebbles and describe the colors. How odd it is that anyone should not see that observation must be for or against some view if it is to be of any service”

But his ambivalence is seen in Darwin's advice to a young scientist:

Let theory guide your observations, but till your reputation is well established be sparing in publishing theory. It makes persons doubt your observations.

The same ambivalence is seen in Einstein. Mitigation skeptics like this quote:

No amount of experimentation can ever prove me right; a single experiment can prove me wrong.

The quote this when the observations show less changes than the model. If the observations show more changes than the model/theory the observations, they quickly forget Einstein and the observations are suddenly wrong.

In practice Einstein was more realistic. Prof in molecular physics [[John Rigden]] wrote in his book about Einstein's wonder year 1905: "Einstein saw beyond common sense and, while he respected experimental data, he was not its slave."

That is perfectly reasonable. When theory and observations do not match, the theory can be wrong, the observations can be wrong and the comparison can be wrong. What is called observations is nearly always something that was computed from observations and also that computation can be imperfect. Only when we understand the reason, can we say what it was.

The main blog of the mitigation skeptical movement, WUWT, on the other hand is famous for calling trying to understand the reasons for discrepancies: "excuses".

Global mean temperature

That was a long introduction to get to the graph I wanted to show, where theory suggests the global mean temperature estimates in some periods may have problems.

The graph was compute by Andrew Poppick and colleagues and it looks as if the manuscript is not published yet. They model the temperature for the instrumental period based on the known human forcings — mainly increases in greenhouse gasses and aerosols (particles from combustion floating in the air) — and natural forcings — volcanoes and solar variations. The blue line is the model, the grey line the temperature estimate from NASA GISS (GISTEMP).

The fit is astonishing. There are two periods, however, where the fit could be better: world war II and the first 40 to 50 years. So either the theory (this statistical model) is incomplete or the observations have problems.

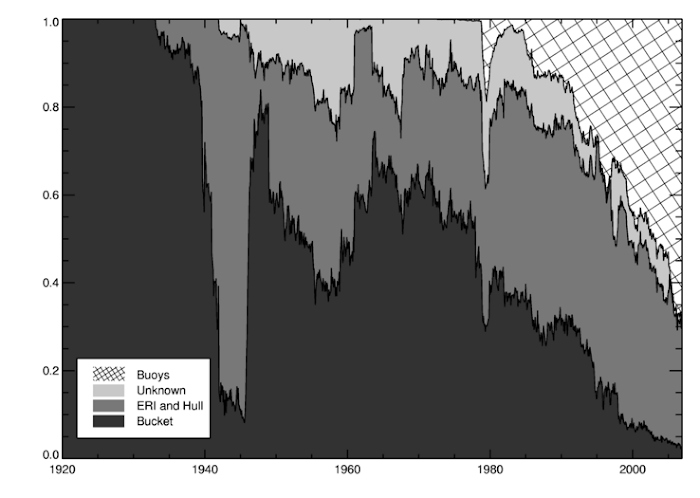

It is expected that the observations in the WWII are more uncertain. Especially the sea surface temperature changes are hard to estimate because the type of ships and thus the type of observations changed radically in this period. The HadSST estimate of the measurement methods is shown below. During WWII American war ships dominated and they mainly used Engine Room Intake observations, whereas before and after the war merchant ship would often measure the temperature of a bucket of sea water.

The figure above are the observational methods estimated by the UK Hadley Centre for HadSST. Poppick's manuscript uses GISTEMP. Its sea surface temperature comes from ERSST v4. (The land data of GISTEMP comes from the stations gathered by NOAA (GHCNv3) and additional Antarctic stations).

ERSST estimates the observational methods of ships by comparing the sea surface temperature to the night marine air temperature (NMAT). This relationship is only stable over larger areas and multiple years. They can thus not follow the fast changes in the WWII observational methods well.

Also for HadSST it is not clear whether these corrections are accurate and they are large: in the order of 0.3°C. What makes this assessment more difficult is that in the beginning of WWII there was a strong and long [[El Niño event]]. Thus a bit of a peak is expected, but it is not clear whether the size is right.

I would not mind if a reviewer would request to add a statistical model that includes El Nino as predictor in Poppick's paper. That would reduce the noise further (part of the remaining noise is likely explained by El Nino) and that would make it easier to assess how well the temperature fits in the WWII.

The Southern Oscilation Index (SOI) of the Australian Bureaux of Meteorology (BOM). Zoomed in to show the period around WWII. Values below -7 indicate El Nino events and above +7 La Nina events.

It would be an important question to resolve. The peak in the WWII is a large part of the hiatus (a real one) we see in the period 1940 to 1980. If you think the peak in the 1940s away, this hiatus is a lot smaller. The lack of warming in this period is typically explained with increases in aerosols. It ended when air pollution regulations slowed the growth of aerosols; especially in the industrialised air quality improved a lot. I guess that if this peak is smaller, that would indicate that the influence of aerosols is smaller than we currently think.

While the observations hardly showed any warming the first 40 to 50 years, the statistical model suggests that there should have been some warming. The global climate models also suggest some warming. And also several other climate variables suggest warming: the warming in winter, the time lakes and rives freeze and break up, the retreat of glaciers, temperature reconstructions from proxies, and possibly sea level rise. See for example this graph of the dates rivers and lakes froze up and broke up.

I wrote about these changes in my previous post on "early global warming". Poppick's statistical model adds another piece of evidence and suggests that we should have a look whether we understand the measurement problems in the early data well enough.

By comparing the observations with the statistical model we can see periods in which the fit is bad. Whether the long-term observed trend is right cannot be seen this way because the statistical model would still fit well, just with a different coefficient for the long-term forcings. This relationship is likely biased in a similar way as the simple statistical models used to estimate the equilibrium climate sensitivity from observations. This model, and thus theory, does provide a beautiful sanity check on the quality of the observations and suggests periods which we may need to study better.

Arguments

Arguments

This is a really good comment and one the deniers don't get. All their hot air about the pause/hiatus and the "excuses" examining the internal variables that could result in such periods is a good example.

Tx

All the best.

I have always been a bit suspicious of the quote, "No amount of experimentation can ever prove me right; a single experiment can prove me wrong" often attributed to Einstein. That quote espouses a naive falsificationism which is inconsistent with the subtle thought of Einstein on the philosophy of science. It turns out the quote appears in none of Einstein's writtings, and though attributed to Einstein by several sources in print, none of those attributions specify at time, place or person to whom it was said. Therefore, the quote must be considered dubious at best.

Einstein has written similar things. In "Induction and Deduction in Physics" he wrote:

And in an unpublished note he wrote:

Also at my blog the main discussion was about the sources for the Einstein quotes. It does not matter much for the story, but I will be more careful next time.

Over at Victor Venema's blog, the comment I liked best was the one that said:

There are other things to keep in mind regarding Einstein quotes.

"The Great Thoughts" compiled by George Seldes and published in 1985, includes the following footnote regarding the Einstein quotes included in it:

"All quotes dated up to October 1954 were acknowledged and corrected by Dr. Einstein, who read the Mss. and replied: "Many things which go under my name are badly translated from German or are invented by other people." Among the paragraphs Dr. Einstein deleted, for example, was his supposed reply "There is no hitching-post in the Universe" to the request for a "one-line definition of the theory of relativity" made by a boat-train reporter the day he arrived in America (December 30, 1930)."

"The main blog of the mitigation skeptical movement, WUWT, on the other hand is famous for calling trying to understand the reasons for discrepancies: "excuses""

The use of the term "excuses" by the likes of WUWT can be "Understood and Explained".

Many people who know they behave unacceptably "excuse" their behaviour by claiming everyone else is like them. If they did not have a way to "excuse" what they can understand is unjustified they would feel obliged to change their thinking, beliefs and behaviours.

Of course, those who are guided by the pursuit of better understanding with an honourable objective, like “the advancement of humanity to a lasting better future for all”, are open to constantly changing their minds, but only when it is justified by the accumulated evidence (and since there is never likely to be evidence regarding spiritual matters they can maintain a scientific way of thinking while maintaining spiritual beliefs).

As Einstein said "Science without religion is lame, religion without science is blind."

So it is possible to "understand and explain" why the likes of WUWT resort to the term "excuses" rather than "explanations". And it is also possible to understand the high number of fundamentalist religious adherents who are in the habit of using “excuses” for their preferred beliefs. But that "understanding and explanation" does not "excuse" what they desire to believe and try to get away with doing.

In my previous comment I had not included another group that always needs "excuses". The fans of full freedom of everyone in Free Market Capitalism.

The understanding and explanations of what is wrong with allowing everyone to be free to do as they please lead to requirements for the advancement of humanity that are contrary to the interests of many people who developed a taste for getting away with benefiting from activities that can be understood to be unacceptable, activities that all of humanity can not be allowed to develop to enjoy, activities that even a portion of humanity cannot continue to benefit from indefinitely on this amazing planet, activities that have to be fought over by people trying to be the ones who get to enjoy the most personal benefit, fighting that has to be "excused".

Even if Einstein didn't say "No amount of experimentation can ever prove me right; a single experiment can prove me wrong", is there still truth or value in the statement?

matematik:

There is a core of truth in this. You cannot prove that a theory is right. Certainty is the realm of religion.

And it is important that a theory can be proven wrong, that it is falsifiable. If not, you did not describe the theory clear enough.

However, actually showing a theory to be wrong is normally not just "one experiment". Because one experiment always tests a multitude of theories. In case of the faster than light neutrinos, a theory that was tested was that the cable was attached well to the instrument. That turned out to be the theory that was refuted and not the theory that nothing can go faster than light.

Does it even matter precisely what Einstein said? We all get the general theme of what he was saying, which is perfectly reasonable, namely that you can't be 100% certain about some theory, or 100% prove a theory. In fact proof really only applies to mathematics.

Maybe one day we would have 100% certainty. However at "this stage" of human development we can't really be 100% for numerous different reasons. For example we can't be certain observations are always 100% correct, and we cant be 100% certain things like inductive logic would always produce the right answer.

But we can be about 99% certain that various theories or laws are correct, at least in a certain range of definable conditions. For example we would have to be at least 99% certain of the theory of evolution.

This is the best we can do, some level of certainty. Humanity either bases it's decisions on science and levels of certainty, or mysticism. Theres no other alternative.

Sometimes we just have to accept some things are certain for all practical purposes. The world is 99.999% certain to be a sphere (or oblate spheroid whatever the correct shape is). It would only be flat if we were all living in some "Matrix" like the movie, and being deceived into thinking it was a sphere. Chances of this are not high.

nigelj @10, it matters because AGW deniers and other pseudoscientists latch on to the Einstein quote and insist that all the entire theory of AGW (or evolution, or the safety of vaccines) has been overthrown by their one preferred experiment that they are probably misinterpretting in any event.

Neither of the actual quotes from Einstein (@2 above) supports this sort of naive falsificationism. It is possible from the second of the quotes that Einstein was a naive falsificationist, but that is not consistent with generally deep thinking about philosophy of science. Certainly, Popper, who Einstein highly praised, was not a naive faslificationist, saying:

(See my discussion here.)

This can be illustrated by Einstein's general theory of relativity, and his cosmological constant which he once described as his greatest mistake, but which is no being rehabilitated. In essence, at the time Einstein formulated the general theory (1915), astronomers believed that the universe consisted of just one galaxy. That theory was not disproved until 1923, by Erwin Hubble. Because a single galaxy is necessarilly non-expanding, Einstein felt a need to modify his theory so that it predicted a non-expanding universe to fit the "observations" of the astronomers.

It may be objected that the non-existence of other galaxies was itself a theory, not an observation, but that misses the point. All observations are theories, if often simpler theories - unless we restrict the term to descriptions of the instensity and relative spacing of various colours, sounds, tastes, smells and sensations. Even the "observation" that the pressure on my fingertips is caused by the cup I can see in my hand goes well beyond the strict data and represents the very often believed, but potentially wrong (at least from a logical point of view) theory of the existence of an external world. Indeed, sometimes such "observations" are falsified in our own experience, as when we have a dream that accounts for a phenomenon in the dream, which upon waking we discover was a real phenomenon intruding into our sleeping mind.

If that is getting too philosophical for you, Victor's example @9 well illustrates the point that "observations" are not just given. They come with certain assumptions which themselves can be falsified. In a similar vain, Eddington's famous observations that "confirmed" general relativity included observations from two instruments. Those from one more closely matched the predictions of General Relativity, while those from the other more closely matched Newton's theory, as interpreted at the time. The later were discarded as inferior, but clearly no simple falsification of Newton was involved. To further complicate things, the discrepant observations were later (1979) reanalyzed as being more in agreement with General Relativity.

Further, as Lakatos said, all new theories are born in a sea of anomalies (ie, of "observations" that contradict the theory but that are put aside in the short term in the hope that later analysis will clear them up). Elsewhere he wrote:

(Foot note 14. It is highly recommended that you read the whole article.)

Tom Curtis @11

Yes I agree that Einsteins "alleged" quote on experiments could be manipulated by climate deniers. However your point seems a little pedantic to me, as we are always going to get this sort of thing from deniers. For example it's well known that a theory can also be falsified by new information or discrepancies, and deniers can point at this as a general belief that any reputable scientist would subscribe to. Sadly denialists will try to find some so called new information, and missunderstand it or twist it.

And basically one experiment could falsify a theory, but it would have to be a convincing experiment replicated etc. The more compelling the theory the more convincing the experiment would have to be.

I was really just making the point that deniers want 100% proof of climate change theory, when this is a strawman argument because 100% proof is impossible in any major theory of science. Proof belongs to mathematics.

Please dont talk down to me about problems of observations. I mentioned the same thing in my post. Try to read past line one.

I'm also well aware that a complex but well established theory like climate change is not falsified by some problem with some specific aspect. Although the usual suspects would swear black and blue it is.

I'd modify Victor's "And it is important that a theory can be proven wrong, that it is falsifiable. If not, you did not describe the theory clear enough." I would make that "...can have the balance of evidence showing it wrong," rather than "proven." Always there are assumptions and uncertainties that come along with evidence both theoretical and observed, which prevent absolutely proving anything either true or false.

nigelj @12, first, I certainly had no intention to "talk down to you". In everything I write at SkS, I am always aware that this is primarilly an educational cite, whose readership is much larger than the number of people who commentate, and who cannot be presumed to have a significant education in science, still less philosophy of science. As a result I am inclined to go back to basics, to spell out things in small steps, and to link to sources of technical terms, even when I know that is not necessary for the person to whom I directly respond. If that has, in this case, created an impression of condescension, I am sorry.

That said, however, your response shows that you have not appreciated, or do not agree with my fundamental point. Quoting Lakatos again, "There are no such things as crucial experiments". No single experiment can ever falsify a theory by itself, still less a scientific research program. That is because every experiment uses instruments that are presumed to operate in a particular way based on yet other theories, so that the "failure" of the experiment calls into question not just the one theory, but all theories involved in the design of the instruments. An experiment, together with an assessment of the relative robustness of the theories under test and involved in understanding the instruments may lead to the dropping of a particular theory as falsified, but that assessment itself involves knowledge of the reliability of the different theories in other experiments, not to mention assessments of their relative cohesion and simplicity.

One experiment may act as the final straw for a given scientist, or a large number of scientists; but if other scientists continue to espouse the theory, that does not thereby make them irrational.

Tom Curtis @14

I accept paragraph one. I also often comment for the wider readership on various subjects, rather than just to convince the person I'm replying to.

Regarding the rest of your comments in paragraphs two and three, I accept one single experiment would not falsify a theory, as all experiments are based on theories regarding instruments and methods, of which we cannot be 100% certain. But how many experiments would you need? It seems the same point applies over and over. One could argue we have 'enough' experiments, and they have strong underlying theories, but all that is rather subjective.

Falsifiability is a good characteristic of a "scientific" theory, but absolutely not an absolutely necessary one. A common example is string theories, which traditionally have not been falsifiable even in principle. Proponents prefer to add "not falsifiable yet," because it seems reasonable to be optimistic about the potential to make them falsifiable. Support for that optimism comes from a team that recently claims at least one flavor of a string theory is potentially falsifiable. In contrast, the supernatural explanation "God did it" for everything is in principle not falsifiable, with no reason for thinking it ever could be falsified. Theories can be scientific and even valuable even if they are not falsifiable, if they rate high on other attributes of good scientific theory, such as fruitfulness, parsimony, and gut-level-explanatory-satisfying.

Yes, nigelj, it is indeed all rather subjective. That's science. Science is judgment and decision making.

Well string theory is many peoples idea of something that isnt science yet because it isnt falsibable even in theory. However, it is actually constrained by observation (ie the vast bulk of physical experimentation) so in that sense I accept it as science. To my mind, science is logic constrained by observation.

Tom Dayton @17

"Science is judgement and decision making."

Fair enough. Could't agree more actually.

Ultimately its also a consensus of the views of scientists that are in agreement over things that are hard to sometimes transparently quantify.

Scientific method is interesting and conventional definitions are fine by me. (observation, idea, experiment etc). However its hard to be precise about the "correct scientific method" beyond this and maybe we should not be too narrow in definitions.

I liked some defintion somebody had "Science is about using your noodle and getting on with it"!

nigelj @15, subjective but not irrational. Specifically, while different scientists may place greater emphasis on different factors (elegance of the theory, experimental data etc), all scientists should be able to agree whether or not a particular experiment is favourable or unfavourable to a particular theory, and to a certain degree, which theory is more favoured by the evidence overall.

That said, there are many theories in which the support of the evidence is so overwhelming relative to competing theories that only a certain bloodiness of mind can jusfify holding onto one of the alternatives. Even so, doing so is still rational provided you keep proper score. Sometimes such bloodiness of mind pays of with a revision of the theory, or new and surprising evidence, throwing everything in a new light, and making the formerly moribund theory the consensus view. On that score, I have no problem with scientists (professional or amateur) rejecting AGW, provided they do not also cherry pick data, employ bogus mathematics, and that they fairly acknowledge the weight of evidence against them; that is, provided they do not take the step from science to pseudoscience.

Further, there are some scientific theories so well supported by the evidence that rejection of them can only be considered irrational (the near sphericity of the Earth comes to mind).

@19, consensus plays a peculiar role in science. It is not, and never should be used as a basis of determining the correctness or otherwise of a theory. However, the days a long past when any scientist can critically analyse all of science, or even all of chemistry, or biology, or physics etc. Ergo, like it or not scientists must rely on theories, the evidence for which they are only superficially aware of. In that situation, they can justifiably accept robust, consensus positions as foundations for further research. If instead they want to reject the consensus position, they need to in fact become expert in the field whose consensus they reject (with the probable consequence that that is the field in which they research and publish) before using the alternate theory as the basis of their future work.

In a similar role, in public policy the consensus position should always be accepted in that the implimenters of the policy will not become sufficiently expert to judge between the consensus position and its alternatives.

Tom Curtis at 20

Yes subjective does not mean irrational. I was being a bit rhetorical and wondering aloud.

I also have no problem with climate sceptics provided they make rational arguments etc as you point out. Scepticism is important and it's important to avoid "group think".

The trouble is those rational sceptics are thin on the ground. We have an army of liars and deceivers who have no conscience about what they say, and others that just can't seem to see reason. This is partly why I post a few comments, as to why I think sceptical arguments that I have seen so far don't make sense.

I made much the same comment above on the earth being a sphere. Some things have such obvious proof / evidence we can accept them as proven for all practical purposes, even if strictly and philosophically nothing can be 100% proven.

One of the issues for me with climate change is there is a vast amount of published science running to thousands of papers, so the only way to figure out where the weight of evidence really is requires assessing all that research. Theres no one defining paper or experiment etc.

No one person can review all this no matter how clever they might be, and so we rely on the IPCC. In that sense consensus is important. It's maybe not ideal, but I just can't see what else we do. In fact the process is basically sound and this is why I get frustrated with criticism of the IPCC.

Tom Dayton:

Whether a theory can be proven wrong (is falsifiable) is a property of the theory. This does not depend on observations/experiments. This question only needs science and reasoning.

The balance of the evidence comes into play for the much more subjective question whether a theory is falsified. I would argue that this is "subjective" during the transition periods between theories. during such a transition (paradigm) change, subjective assessments of elegance, conciseness, trust in experiments, adding apples and oranges (theory A does X well, theory B does Y well) come into play.

Once the dust settles, the weight of the evidence normally clearly points to one theory.

It is interesting when a scientist thinks to have a research program that can challenge the current dominant paradigm. Those are the big names you'd like to listen to.

A scientist who is not able to honestly acknowledge that current evidence supports the dominant paradigm is, however, likely a really bad scientist and also not likely to topple the paradigm. You have to know what you are fighting.