Global Warming: Not Reversible, But Stoppable

Posted on 19 April 2013 by Andy Skuce

Let's start with two skill-testing questions:

1. If we stop greenhouse gas emissions, won't the climate naturally go back to the way it was before?

2. Isn't there "warming in the pipeline" that will continue to heat up the planet no matter what we do?

The correct answer to both questions is "no".

Global warming is not reversible but it is stoppable.

Many people incorrectly assume that once we stop making greenhouse gas emissions, the CO2 will be drawn out of the air, the old equilibrium will be re-established and the climate of the planet will go back to the way it used to be; just like the way the acid rain problem was solved once scrubbers were put on smoke stacks, or the way lead pollution disappeared once we changed to unleaded gasoline. This misinterpretation can lead to complacency about the need to act now. In fact, global warming is, on human timescales, here forever. The truth is that the damage we have done—and continue to do—to the climate system cannot be undone.

The second question reveals a different kind of misunderstanding: many mistakenly believe that the climate system is going to send more warming our way no matter what we choose to do. Taken to an extreme, that viewpoint can lead to a fatalistic approach, in which efforts to mitigate climate change by cutting emissions are seen as futile: we should instead begin planning for adaptation or, worse, start deliberately intervening through geoengineering. But this is wrong. The inertia is not in the physics of the climate system, but rather in the human economy.

This is explained in a recent paper in Science Magazine (2013, paywalled but freely accessible here, scroll down to "Publications, 2013") by Damon Matthews and Susan Solomon: Irreversible Does Not Mean Unavoidable.

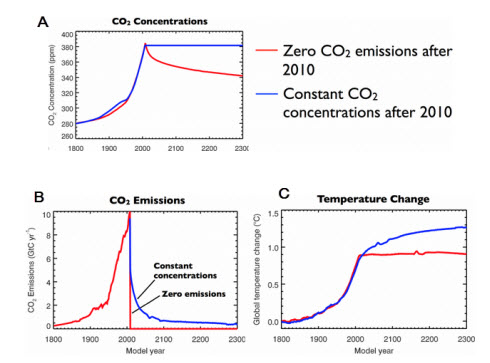

Since the Industrial Revolution, CO2 from our burning of fossil fuels has been building up in the atmosphere. The concentration of CO2 is now approaching 400 parts per million (ppm), up from 280 ppm prior to 1800. If we were to stop all emissions immediately, the CO2 concentration would also start to decline immediately, with some of the gas continuing to be absorbed into the oceans and smaller amounts being taken up by carbon sinks on land. According to the models of the carbon cycle, the level of CO2 (the red line in Figure 1A) would have dropped to about 340 ppm by 2300, approximately the same level as it was in 1980. In the next 300 years, therefore, nature will have recouped the last 30 years of our emissions.

Figure 1 CO2 concentrations (A); CO2 emissions (B) ; and temperature change (C). There are two scenarios: zero emissions after 2010 (red) and reduced emissions producing constant concentrations (blue). From a presentation by Damon Matthews, via Serendipity.

So, does this mean that some of the climate change we have experienced so far would go into reverse, allowing, for example, the Arctic sea ice to freeze over again? Unfortunately, no. Today, because of the greenhouse gas build-up, there is more solar energy being trapped, which is warming the oceans, atmosphere, land and ice, a process that has been referred to as the Earth's energy imbalance. The energy flow will continue to be out of balance until the Earth warms up enough so that the amount of energy leaving the Earth matches the amount coming in. It takes time for the Earth to heat up, particularly the oceans, where approximately 90% of the thermal energy ends up. It just so happens that the delayed heating from this thermal inertia balances almost exactly with the drop in CO2 concentrations, meaning the temperature of the Earth would stay approximately constant from the minute we stopped adding more CO2, as shown in Figure 1C.

There is bad news and good news in this. The bad news is that, once we have caused some warming, we can’t go back, at least not without huge and probably unaffordable efforts to put the CO2 back into the ground, or by making risky interventions by scattering tons of sulphate particles into the upper atmosphere, to shade us from the Sun. The good news is that, once we stop emissions, further warming will immediately cease; we are not on an unstoppable path to oblivion. The future is not out of our hands. Global warming is stoppable, even if it is not reversible.

Warming in the pipeline

Bringing human emissions to a dead stop, as shown by the red lines in Figure 1, is not a realistic option. This would put the entire world, all seven billion of us, into a new dark age and the human suffering would be unimaginable. For this reason, most climate models don’t even consider it as a viable scenario and, if they run the model at all, it is as a "what-if".

Even cutting back emissions severely enough to stabilize CO2 concentrations at a fixed level, as shown in the blue lines in Figure 1, would still require massive and rapid reductions in fossil fuel use. But, even this reduction would not be enough to stop future warming. For example, holding concentration levels steady at 380 ppm would lead to temperatures rising an additional 0.5 degrees C over the next two hundred years. This effect is often referred to as “warming in the pipeline”: extra warming that we can’t do anything to avoid.

The most important distinction to grasp, though, is that the inertia is not inherent in the physics and chemistry of the planet’s climate system, but rather in our inability to change our behaviour rapidly enough.

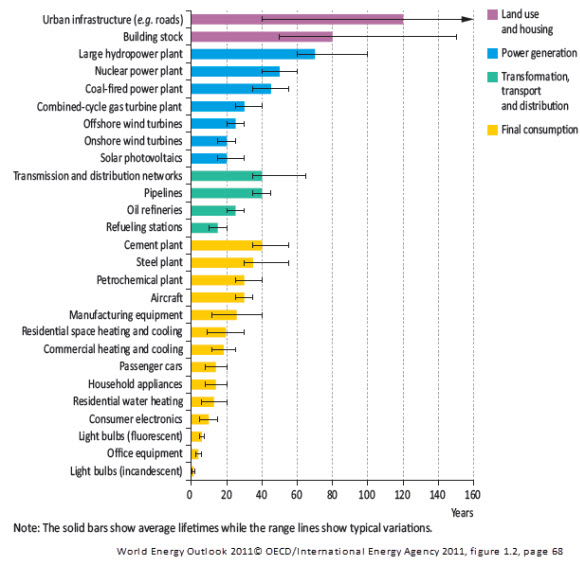

Figure 2 shows the average lifetimes of the equipment and infrastructure that we rely upon in the modern world. Cars last us up to 20 years; pipelines up to 50; coal-fired plants 60; our buildings and urban infrastructure a century. It takes time to change our ways, unless we discard working vehicles, power plants and buildings and immediately replace them with, electric cars, renewable energy plants and new, energy-efficient buildings.

Figure 2 Average expected lifetimes for equipment and infrastructure.

“Warming in the pipeline” is not, therefore, a very good metaphor to describe the natural climate system, if we could stop emissions, the warming would stop. However, when it comes to the decisions we are making to build new, carbon-intensive infrastructure, such as the Keystone XL pipeline, the expression is quite literally true.

Wrinkles

The Matthews and Solomon paper only deals with CO2. Short-lived greenhouse gases like methane are not considered in the study and nor are aerosols. Stopping fossil fuel burning, especially coal, would reduce aerosol (small particle) emissions, reducing their current shading effect and increasing warming. On the other hand, stopping fossil fuel consumption would decrease methane emissions and thus decrease warming even more than these authors have projected. It may turn out that these two effects balance out.

The other potential problem is that the carbon cycle model that Matthews and Solomon use may not be as well behaved as they predict. For example, MacDougall et al (2012) ran their own "industrial shutdown" experiments and found that future CO2 concentrations in their most likely climate sensitivity case remained steady, because emissions from the permafrost (see this SkS post, Figure 3) balanced the reductions from other carbon sinks. This means that a shutdown of human emissions could, in practice, look more like the blue lines in Figure 1.

The likelihood and severity of unexpected carbon-cycle feedbacks, including the way in which the ocean absorbs CO2, will be larger when there has been more warming—due to more emissions or higher climate sensitivities, or both—but this only increases the need for prompt and substantial action in reducing emissions.

Takeaway points

- The warming we have caused by our emissions of carbon cannot be undone.

- The additional future warming we will experience will be a result of our current and future emissions.

- The inertia in the climate system is not natural, but human.

- Emissions avoided today mean less warming tomorrow, and forever.

The confusion that many of us have with answering the two questions posed at the beginning of the article is probably rooted in our mental models, one being that the climate change will naturally revert back to normal; the other that the changes in the climate system have unstoppable momentum. Neither view is correct and they both favour inaction; one by implying that we can wait to fix the problem, the other by implying that it is already too late.

Metaphors and mental models are essential to understanding the way complex systems work. But they can mislead as well as illuminate. Here are a couple of analogies that I have come up with, but they are not perfect either. Maybe readers can do better.

- We can't put toothpaste back in the tube once we have accidentally squeezed too much out, but we can prevent any further waste by stopping squeezing.

- Like a bull in a china shop, we can't unbreak what we have already broken, but once the rampaging stops, no more damage will be done.

Other articles on the paper by Matthews and Solomon can be found at Climate Central (Andrew Freedman) and Serendipity (Steve Easterbrook).

Arguments

Arguments

KR:

I find this approach delightfully optimistic in its child-like charm, yet completely unrealistic.

Reminds me of Star Trek, where apparently GDP has grown so much that nobody actually needs to work nor earn money any more, they just do whatever takes their fancy and everything is free.

Still can't figure out why some fancy being starship captains and others "fancy" being bossed around rather than sitting at home all day watching TV and playing computer games...

@Mark Bahner #96:

In response to Tom Curtis, you state, When we get your predictions, we can figure out whether Robin Hanson, I, or you are right about world GDP growth in the 21st century.

Exactly who is the "we"?

Exactly how are "we" going to figure out who is right?

Mark seems to not be aware of the purpose of economic forecasting. You, literally, can not predict the future. The point of forecasting is to establish potential outcomes in order to mitigate risk. No one is going to take the best case scenario and base their plans on that.

The thing about forecasting is, no matter what, you will be wrong. You can create boundary conditions and base plans on that, but you can't build a rosy scenario where all problems are magically solved and expect anything like that is going to happen.

JasonB writes: "I can't speak for Tom but I have published (a long time ago) in the field of AI and I make a living today creating technology that greatly enhances productivity so I guess I'm one of the "doers" (as opposed to "thinkers") in that area."

You're a "doer" in the field of how AI affects macroeconomic growth? So...you've had some courses in macroeconomics? Or even an advanced degree, perhaps? You know your way around basic economic models like the Solow-Swan model?

Estimates vary on the processing power of the human brain, from about 10 petaFLOPS up to about 100 petaFLOPS, but somewhere in the middle seems reasonable.

The estimates I've see run from 0.5 petaFLOPs (Moravec) to 20 petaFLOPs (Kurzweil). So yes, "somewhere in the middle...towards the lower end" seems reasonable.

The computing power is there.

No, the computing power is not there. Using an estimate of say, 20 petaFLOPS for a human brain, and the human population is approximately 7 billion. So that’s 140 billion petaFLOPs. What was the total number of petaFLOPS added by all computers in the world in 2012? How many will be added by computers in 2022? 2032? 2042?

"Why? You've made that offer a couple of times now and I can't see what possible value there would be in any of our predictions of future GDP growth,..."

I offered $20 to Tom Curtis to predict world per-capita economic growth in each decade of the 21st century. I offered you $20 to predict world per-capita GDP in 2050 and 2100, but also many other parameters for 2050 and 2100: 1) world life expectancy at birth, 2) global CO2 emissions, 3) atmospheric CO2 concentration, 4) global surface temperature anomaly (NASA GISTEMP), 5) global malaria deaths, 6) Beijing annual average PM10 concentration (that’s particulate matter less than 10 microns), 7) percent of world population without access to proper sanitation, 8) global sea level rise (relative to 2013), 9) percentage of species in the 2010 IUCN “Red List” listed as “vulnerable,” “endangered,” “critically endangered,” and “extinct in the wild” that will be declared extinct, and 10) the cost to desalinate 1000 gallons of seawater.

The value of this information is a simple matter of science. Science consists of one person predicting “a”, and another person predicting “b” (each with explanations for why they are making their predictions) and then observing to see which predictions are correct (or it could be “c” and neither is correct). Or both persons could agree on “a” or “b” in which case there’s not a point in further debate.

Additionally, in the case of my asking for your predictions for all those parameters (not just GDP) is to see whether or not we agree regarding some parameters that I think reflect "quality of life" (e.g. life expectancy at birth, number of malaria deaths, people with access to adequate sanitation, etc.).

Oops. Here is a repeat of that post, with JasonB's words as quotations (it may be confusing the way I first did it):

JasonB writes: "I can't speak for Tom but I have published (a long time ago) in the field of AI and I make a living today creating technology that greatly enhances productivity so I guess I'm one of the "doers" (as opposed to "thinkers") in that area."

You're a "doer" in the field of how AI affects macroeconomic growth? So...you've had some courses in macroeconomics? Or even an advanced degree, perhaps? You know your way around basic economic models like the Solow-Swan model?

The estimates I've see run from 0.5 petaFLOPs (Moravec) to 20 petaFLOPs (Kurzweil). So yes, "somewhere in the middle...towards the lower end" seems reasonable.

No, the computing power is not there. Using an estimate of say, 20 petaFLOPS for a human brain, and the human population is approximately 7 billion. So that’s 140 billion petaFLOPs. What was the total number of petaFLOPS added by all computers in the world in 2012? How many will be added by computers in 2022? 2032? 2042?

I offered $20 to Tom Curtis to predict world per-capita economic growth in each decade of the 21st century. I offered you $20 to predict world per-capita GDP in 2050 and 2100, but also many other parameters for 2050 and 2100: 1) world life expectancy at birth, 2) global CO2 emissions, 3) atmospheric CO2 concentration, 4) global surface temperature anomaly (NASA GISTEMP), 5) global malaria deaths, 6) Beijing annual average PM10 concentration (that’s particulate matter less than 10 microns), 7) percent of world population without access to proper sanitation, 8) global sea level rise (relative to 2013), 9) percentage of species in the 2010 IUCN “Red List” listed as “vulnerable,” “endangered,” “critically endangered,” and “extinct in the wild” that will be declared extinct, and 10) the cost to desalinate 1000 gallons of seawater.

The value of this information is a simple matter of science. Science consists of one person predicting “a”, and another person predicting “b” (each with explanations for why they are making their predictions) and then observing to see which predictions are correct (or it could be “c” and neither is correct). Or both persons could agree on “a” or “b” in which case there’s not a point in further debate.

Additionally, in the case of my asking for your predictions for all those parameters (not just GDP) is to see whether or not we agree regarding some parameters that I think reflect "quality of life" (e.g. life expectancy at birth, number of malaria deaths, people with access to adequate sanitation, etc.).

One final thing about the predictions I requested JasonB to make. (Offered him $20 to make! I challenge anyone to make me similar offers!)

The table with the various parameters is located here. That table has the parameter values circa 2012 (and the units, such as for PM10 concentration), for greater ease in making predictions. For example, malaria deaths are estimated at 770,000 in the table. But I've seen a Lancet article up to 1.2 million. Similarly, the estimate of 37% of the world without proper sanitation circa 2012 is just one estimate. So the idea would be to assume that the number I gave in the table was correct, and go off of that.

Mark Bahner, I think you have missed the point, regardless of the PFLOPS available, we don't know how to write the software, so the point is moot.

Secondly, making projections based on speculation is not science, it is futurology. In science whether a projection is worth paying attention to (or for that matter making) rather depends on the strength of the supporting argument/evidence. Merely challenging someone to make a prediction so we can wait and see who is right is not science, and comes across as a rhetorical device to avoid addressing the factual basis for your position.

At the end of the day, physics is a lot more predictable than economics, which suggests physics is a more reliable solution to the problem than deligating the problem to others in the hopes that they can fix it more cheaply.

Rob Honeycutt makes this remarkable comment:

Rob, I have predicted the future:

And Nobel Laureate Robert Lucas Jr. predicted the future in his Journal of Economic Perspectives article. The difference between our two predictions is that I think that the development of artificial intelligence will greatly increase economic growth, whereas Robert Lucas Jr. either did not consider the development of artificial intelligence and its effects on economic growth (most likely) or considered the development of artificial intelligence, but thought it would not affect economic growth (possible--I've never had any contact with him--but I think highly unlikely).

Further, the Long Bets site alone has many other economic predictions, such as #626: "The United States will not experience hyperinflation (defined by 3 consecutive months of 6% Month over Month inflation according to the Billion Prices Project measurement of MoM inflation) from April 17th 2012 to April 17th 2017. ”

No, I will be right if the world per-capita GDP (in year 2000 dollars) exceeds $13,000 in the year 2020, $31,000 in 2040, $130,000 in 2060, $1,000,000 in 2080, and $10,000,000 in 2100.

Those predictions are not a "rosy scenario." At the time I made the Long Bets #194 I hadn't done my calculation of the number of human brain equivalents added every year. Based on that calculation, I think only the 2020 prediction is potentially too high. I think the others will be way too low. So if I make it past the 2020 prediction of $13,000 (in year 2000 dollars), I think there's smooth sailing to the end of the century. (Barring takeover by Terminators or global thermonuclear war, of course.)

Mark... You have not "predicted the future" for the coming century. You have put forth predictions about the future. Not only that, you've made predictions about things that you will never know.

I can make a prediction that pigs will develop the capacity to vocalize their thoughts in 2150, and I can make grand bets on the accuracy of the prediction, but none of us will be there to see it.

Making bets you can never collect on borders on delusional.

You say, " Based on that calculation, I think only the 2020 prediction is potentially too high. I think the others will be way too low." And then you add, "(Barring takeover by Terminators or global thermonuclear war, of course.)"

So, even you are already saying that you are likely going to be wrong.

(Psst. Also, you might take strong notice of the fact that China is ramping down it's red-hot economic growth of the past 30 years.)

And Mark... I just don't think you get the point to economic predictions. Everyone understands they're wrong. I'll say it again, you can't predict the future.

You can explore potential outcomes. You can discuss market influence that might or might not come about. You can discuss trends, opportunities, etc.

They way people use this information is so they can mitigate risk.

The problem with what you're doing is, you're taking your assumptions as fact. I'm sorry but you just don't have any more insight than the next person on future facts.

Mark Bahner @ 105,

You're a "doer" in the field of how AI affects macroeconomic growth?

No, I'm a "doer" in the field of AI, which gives me a much better idea of the problems that need solving and the likelihood of fantasies about its capabilities in the next few decades coming true than a macroeconomist who has NFI about the subject and thinks it all boils down to FLOPS/$.

You know your way around basic economic models like the Solow-Swan model?

As it happens, I actually did some software development for an economics professor to earn extra money while I was a postgrad and my observation at the time was that the problems in economics are either trivial to solve ("You've found an analytic solution! Well done! I'm sure that those simplifying assumptions you made do hold in the real world...") or so intractable that solutions aren't possible (or meaningful). The paper you presented has done nothing to dispel that notion.

No, the computing power is not there. Using an estimate of say, 20 petaFLOPS for a human brain, and the human population is approximately 7 billion. So that’s 140 billion petaFLOPs.

Why would an AI's processing power need to be comparable to the combined processing power of the entire human race? We can't network our brains together to achieve higher levels of intelligence (in fact, evidence suggests the opposite...) so the total figure is meaningless. If a computer had more processing power than a single human brain and we knew how to harness that processing power to create an AI then there's no reason to believe that a smarter-than-human AI wouldn't result. And, unlike humans, we can always build more powerful computers (the first exaFLOPS computer is expected by about 2018, which would have the processing power of 50 humans according to your estimate) so there's no real upper limit to intelligence in that regard.

The problem is that it's still just a very fast calculator.

If we ever do manage to crack that nut — and this is still an open question — then it wouldn't be suprising for this genius-level AI to set about writing its own AI software that was better than what we could conceive, and lead to the rapid escalation in artificial intelligence known as the technological singularity, at which point all bets are off.

In the meantime, we have a gradual and hard-fought increase in "intelligence" that really does improve productivity (or else I'd be out of a job), but it's been going on for a long time now and it hasn't seen the magical boost in GDP that your link suggested, as demonstrated by Tom Curtis. Moreover, as we are less and less constrained by the computational abilities of the machines we are using, the more and more obvious it becomes that the constraints are us, and so the less impact each successive improvement in hardware has. (Some examples to ponder: how much better are word processors today than they were five years ago? Ten years ago? 15 years ago? 20 years ago? During the 80s and 90s improvements were obvious; now the only way you can tell which version you're using is the arbitrary cosmetic changes introduced to differentiate the products. What about games, or film CGI? In the beginning there were massive improvements in hardware and software every few years that allowed more and more realism to be introduced; now each generation is much like the last. This tailing off in advancement is normal as technology matures, and completely the opposite of what your forecast assumes.)

The bottom line is that there's no evidence that AI will be the magic bullet that makes out-of-this-world growth rates of GDP possible, and if AI really did make such a massive breakthrough, there's a good chance it would be the end of us anyway so it's perhaps not something to hope for.

The value of this information is a simple matter of science. Science consists of one person predicting “a”, and another person predicting “b” (each with explanations for why they are making their predictions) and then observing to see which predictions are correct (or it could be “c” and neither is correct). Or both persons could agree on “a” or “b” in which case there’s not a point in further debate.

The problem is that (a) the predictions are utterly worthless and (b) the timeframes are so long that we wouldn't even know who turned out to be correct.

The fact that you are willing to give people $20 to just Make Stuff Up is consistent with the value you place on other worthless projections, I suppose.

I think it's also worth pointing out that the difference between these "predictions" and the IPCC's scenario-based projections is that the latter allow us to evaluate the likely effects of decisions that we make today to aid our decision making. The equivalent in your case would be a scenario where the AI Silver Bullet hits, malaria is cured, etc., etc. — in other words, those are your inputs, your assumptions for your scenario, not a prediction of the future.

Additionally, in the case of my asking for your predictions for all those parameters (not just GDP) is to see whether or not we agree regarding some parameters that I think reflect "quality of life" (e.g. life expectancy at birth, number of malaria deaths, people with access to adequate sanitation, etc.).

Suppose, for the sake of argument, that the number of malaria deaths reaches zero because e.g. a cure has been found by then. How does that justify pushing the CO2 drawdown problem onto them? It's as if you are saying "Hey, they will be better off than us because they won't have to deal with problem X, therefore we can burden them with problem Y".

You also seem to be forgetting that there are plenty of countries in the world today that don't have malaria. Doesn't that mean that those countries should start reducing CO2 on that basis?

In the context of the ononging discussion of what the future portends, the following paragraph jumped-out at me when I read Tom Englehardt's essay, And Then There Was One: Imperial Gigantism and the Decline of Planet Earth posted May 7 on TomDispatch.com.

There is a fundamental fallacy where Mark states:

"The value of this information is a simple matter of science. Science consists of one person predicting “a”, and another person predicting “b” (each with explanations for why they are making their predictions) and then observing to see which predictions are correct (or it could be “c” and neither is correct). Or both persons could agree on “a” or “b” in which case there’s not a point in further debate."

What Mark is describing is a "controlled experiment." His predictions are not controlled experiments. He ignores a certain level of randomness in the system. Just because prediction "a" might have been correct does not necessarily mean that the methods used by "a" were better than those of "b" when the experiment takes place in an uncontrolled environment, like world economics.

Again, you can use various methodologies to establish a range of outcomes in order to better constrain uncertainties about future events. You can't use methodologies to predict the future.

Think of it this way. There is some young, hyper-brilliant kid recently born who has the capacity to understand the AI issue better than anyone ever has. That person could grow up to fundamentally change the future of the human race by the year 2040. But, as fate would have it, that child is killed in an auto accident at age 9.

This is what bugs me about what Mark is putting forth. His "predictions" include highly uncertain events occurring at unknown points in the future. So, relative to how we respond today to the challenges humanity faces down the road, his predictions are completely without value.

My issue with Mark Bahners projections are that they are a combination of cornucopian thinking (all needs for the future can be met by continuing advances in technology, with an underlying assumption of extremely low costs - no limits to growth) and the assumption of numerous black swan events (AI singularity, economic growth an order of magnitude that which has been observed, revamping of all methods of production without economic upheaval, etc).

These are not reasonable assumptions, or realistic projections - they are just wishful thinking.

And they ignore what has been determined to date - that mitigating further greenhouse warming by reducing emissions will be far less expensive than adapting to it later, or diverting the resources/energy to try to sequester CO2 released by continued "Business as Usual" behavior. The economically sensible path is to minimize the GHG problem as much as possible, not to band-aid it later on.

Cornucopian/black-swan goals like his, to me, represent little more than an avoidance of the issues - an attempt to kick the problems down the road under wishful projections that the costs down the road will be trivial.

Personally, I would rather address the issues now - based on supportable economic predictions that current action will cost far less than future re-actions.

I believe we can all agree that humans require food and water to subsist. In the context of the ongoing discussion of what manmade climate change may wrought in the near future, here is very sobering assessment.

Source: Are We Doomed to Food Insecurity? New study shows billions more people reliant on food imports in 2050 by Andrea Germanos, Common Dreams. May 8, 2013

[DB] And with that, we are done here, as we have erred well into sloganeering territory. Anyone wishing to engage Mark further on this may do so at his blog:

http://markbahner.typepad.com/

Let us return now to the OP of this thread, Global Warming: Not Reversible, But Stoppable

How neat is that, Mark was wrong about the global GDP growth into 2020, its actually significantly higher than what he said!

[JH] Please provide the source of your information.