Rising seas could ease coral bleaching but will be ‘too little too late’

Posted on 22 September 2016 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Carbon Brief by Robert McSweeney

Coral reefs could receive an unforeseen benefit from global sea level rise, a new study suggests.

Deeper waters over shallow reefs could alleviate the extreme temperatures that corals are exposed to, the study says, potentially easing coral bleaching caused by ocean warming.

But other scientists tell Carbon Brief that coral bleaching is already so widespread that any alleviation from sea level rise is unlikely to counter the impact of increasing temperatures.

Coral bleaching

The global ocean surface is currently warmer than it has been at any point in the observed record. In 2015, for example, global sea surface temperature was 0.33-0.39C higher than the 1981-2010 average, and 0.74C higher than the average for the 20th century.

Ocean warming arguably poses the biggest threat to the world’s coral reefs, says the new Science Advances paper, as it increases the likelihood of coral bleaching events. High temperatures stress the corals, to the point that they are forced expel the tiny colourful algae living in their tissues – known as zooxanthellae – leaving behind a stark white skeleton.

While a bleached coral reef is not dead, as the algae provide the coral with energy through photosynthesis, the coral cannot grow without them. A coral can recover from a single bleaching event, but persistently high temperatures can kill off entire reefs.

Research suggests that a global average temperature rise of 2C above pre-industrial levels could see long-term degradation of virtually all the world’s coral reefs. And even a more ambitious temperature limit of 1.5C could see 90% of coral reefs at risk of bleaching by 2050.

The study’s findings suggest that rising sea levels could help buffer the temperature extremes that corals are exposed to by increasing the volume of water the corals are surrounded by.

Documenting the dead coral after the bleaching event at Lizard Island on the Great Barrier Reef, captured by the XL Catlin Seaview Survey in May 2016.

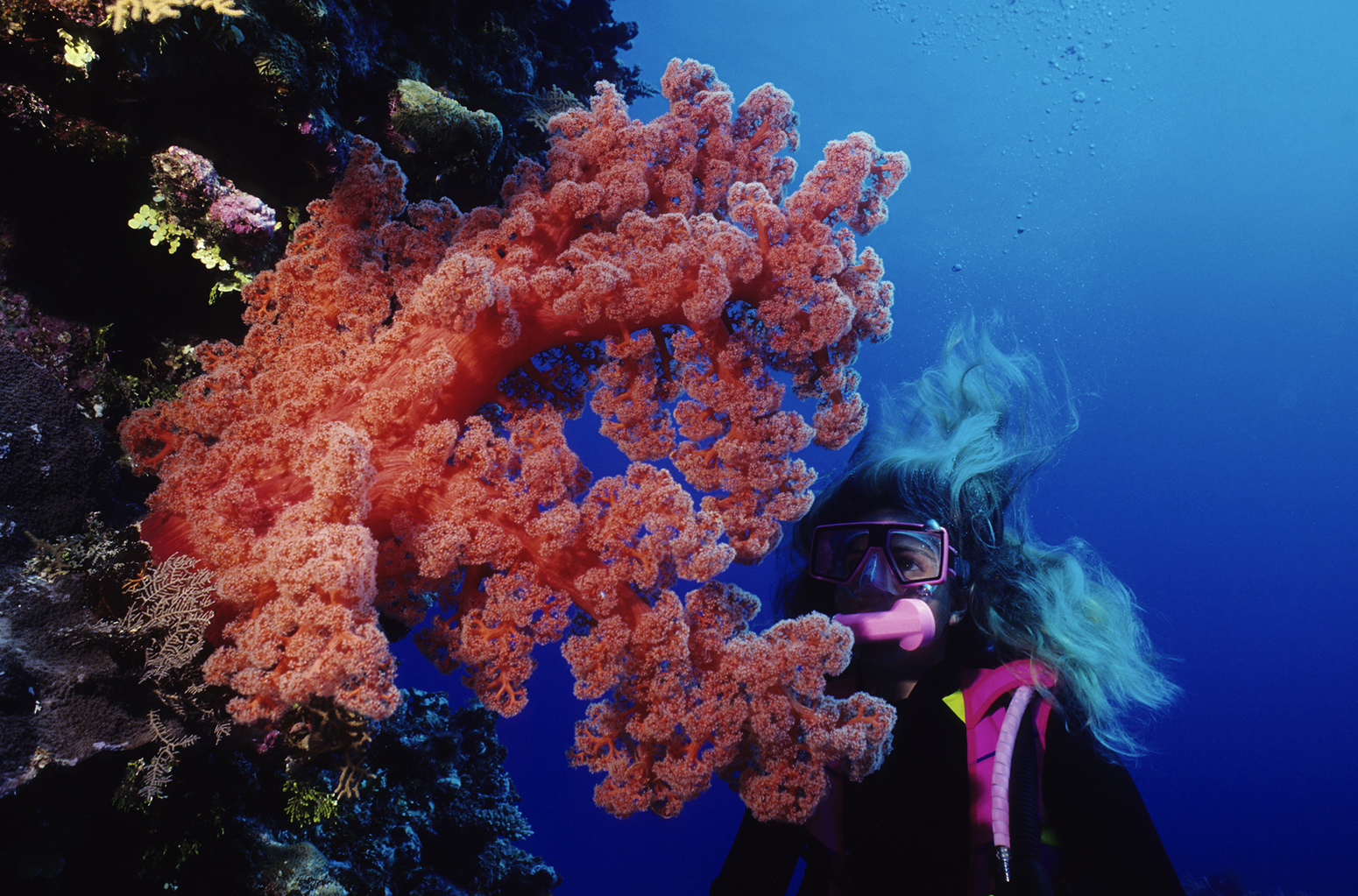

Diver examines healthy giant red soft coral on the Great Barrier Reef. Photo: Tammy616/E+/Getty Images.

Turning tides

The study focuses on corals in shallow reefs that are typical of warm, clear tropical waters. Being in shallow water mean water temperatures often rise much higher and fall much lower than in the deeper ocean. This is because there is less water for the sun’s energy to heat up, and less water to hold onto that heat when temperatures fall during the night.

Tides play an important role in the highs and lows of daily sea temperatures in coral reefs, says lead author Prof Ryan Lowe, from the University of Western Australia. He explains to Carbon Brief:

“Maximum temperatures are reached at the end of low tide [during the day], when shallow water that has accumulated on the reefs has been able to warm up the most. The opposite happens at night – minimum temperatures occur when low tide aligns with the middle of the night, when there is most heat loss from reefs to the atmosphere.”

Most reefs experience semi-diurnal tides, which means they get two high tides and two low tides each day.

During fieldwork on the Kimberley coast of northwestern Australia, Lowe and his colleagues found that sea temperatures on the region’s coral reefs could fluctuate by as much as 10C each day.

They built a computer model to understand how the cycle between day and night and high and low tides affects temperature extremes on coral reefs. They also included two scenarios of future sea level rise into their modelling. The first scenario is for 0.7m of sea level rise by the end of this century, which is based on projections (pdf) from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) under high emissions (RCP8.5). The second scenario is for 1.5m, which is higher than any IPCC projection, but is based on studies of the impact of 4C of global temperature rise.

The researchers find that higher sea levels could reduce the size of the temperature extremes as tides flow in and out. They suggest this could help ease heat stress on the corals.

Running their model for six different shallow reefs in the Indian and Pacific Oceans, the results show that 0.7m of global sea level could reduce the magnitude of temperature extremes by up to 65%. For 1.5m, the reduction is as much as 86%.

One of the paper’s case studies is the coral reefs on Warraber Island off the northern coast of Queensland, where sea surface temperatures currently hit around 2.5C above and below the daily average as the tide comes in and goes out. But with 0.7m or 1.5m of sea level rise, this size of this daily fluctuation could reduce to 1.9C or 0.7C, respectively.

The findings show that average water depth over a reef is a critical factor for temperature extremes, says Lowe:

“Rapid sea level rise can thus significantly reduce the magnitude of current diurnal temperature extremes on reef by – in some cases – up to around 80% of present values.”

‘Too little too late’

While the study suggests that daily extremes in water temperature might decrease for coral reefs, it doesn’t demonstrate how this reduces the heat stress that accumulates in corals over time, says Dr Ruben van Hooidonk, a scientist at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), who wasn’t involved in the study. He tells Carbon Brief:

Hooidonk also says the scale of recent bleaching events – particularly in shallow waters – indicates that temperature change is past the point where other processes can save the corals from bleaching:

“Sea level change might bring a bit of cooling, but because it is such a slow process and most of the world’s reefs are already projected to bleach annually under current conditions by mid-century, it might be too little too late.”

Dr Mark Eakin, coordinator of NOAA’s Coral Reef Watch programme, who also wasn’t involved in the study, says the implications of the study are not very significant for ensuring the future of coral reefs:

“Unfortunately, rising ocean temperatures are causing corals to bleach and die not only on shallow lagoonal reefs but also in deeper lagoons… In fact, we have been receiving reports of corals bleaching and dying during the current global bleaching event down to 40-50 metres.”

There are also other negative impacts of sea level rise on corals to consider, Eakin notes. For example, deeper water puts corals more at risk from wave damage, and more coastal erosion means corals are more likely to be affected by increasing amounts of sediment.

Overall, Eakin is unconvinced that global sea level rise will counter the impacts of continued ocean warming:

“I really wish there was an indication that rising sea level would offset the severe impact rising temperatures are having on corals. Unfortunately, this seems quite unlikely.”

Lowe, R. J. et al. (2016) Rising sea levels will reduce extreme temperature variations in tide-dominated reef habitats, Science Advances, doi:10.1126/sciadv.1600825

Arguments

Arguments

Comments