How weather forecasts can spark a new kind of extreme-event attribution

Posted on 3 January 2022 by Guest Author

This is a re-post from Carbon Brief

Extreme weather events across the world this year have been hitting the headlines at an alarming rate.

To name a few, 2021 has seen flooding in central Europe, China and New York, a record temperature of 49.6C in Canada and wildfires in Siberia, North America and the Mediterranean.

With each tragic event comes the question of whether human-caused climate change made it more severe or more likely. The burgeoning field of climate change “attribution” has stepped up to the challenge. While 10 years ago it might have taken months to fully analyse an individual weather event, scientists are now able to provide an answer in just days or weeks.

Because we cannot make direct observations of a world without human influence on the climate, all attempts to answer this question involve some kind of modelling. However, traditional climate models can struggle to simulate the most extreme weather events. To deal with these compromises, researchers have traditionally relied on comparing results from several different approaches to assess the robustness of their conclusions.

We suggest that a better approach would be to use numerical models that have demonstrated their ability to simulate the event in question through a successful – or at least reliable – weather or seasonal forecast.

In our recent study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, we demonstrate – for the first time – an attribution study that uses a state-of-the-art operational weather forecast model. We tested our approach by assessing the European winter heatwave of 2019 – an event the model successfully predicted.

We find that the direct impact of the extra carbon dioxide (CO2) that humans have pumped into the atmosphere made the event 42% more likely for the British Isles and at least 100% (two times) more likely for France.

Extreme event attribution

In order to quantify how global warming has affected an extreme weather event, scientists flip the focus of the question to look at what might have happened in a world without any human influence on the climate.

Since there is not an Earth without human influence, we have to turn to global climate models to explore this question. These models incorporate all the physics of what we know about the Earth system and allow us to run these kinds of “what if” experiments.

Using the models, we perform simulations of both the real “factual” world, but also an alternative “counterfactual” world, in which humanity has not emitted hundreds of billions of tonnes of CO2 and other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

We then compare the weather in these two simulations to see if – for example – we are seeing more occurrences of the event we are interested in, or if those occurrences are more intense.

In order to have confidence in the results we find, we do not just run the model once – we run these models tens to hundreds of times to build up a full picture of the weather in the two worlds.

However, while climate models are an incredible feat of modern science – worthy of a Nobel Prize – they are not perfect. Climate models have biases and deficiencies – many of which we know about – that affect how much faith we can have in the answers they give us about something as complex as an individual weather event.

For example, we know that many climate models struggle to simulate sufficient numbers and persistence of high-pressure “blocking” weather patterns over Europe. These circulation patterns are often involved in the heat extremes that the continent experiences.

In our paper, we instead turn to a natural alternative to climate models that could provide us with a more robust answer to the same question: weather forecast models.

Numerical weather prediction

Weather forecast models – sometimes called “numerical weather prediction” or NWP models – and climate models are really two sides of the same coin. Some institutions involved in both weather forecasting and climate change projections use different configurations of the same model for seperate weather and climate applications. One example is the UK Met Office’s “unified model”.

However, due to the value of a good weather forecast, NWP models are generally more detailed than their climate model cousins.

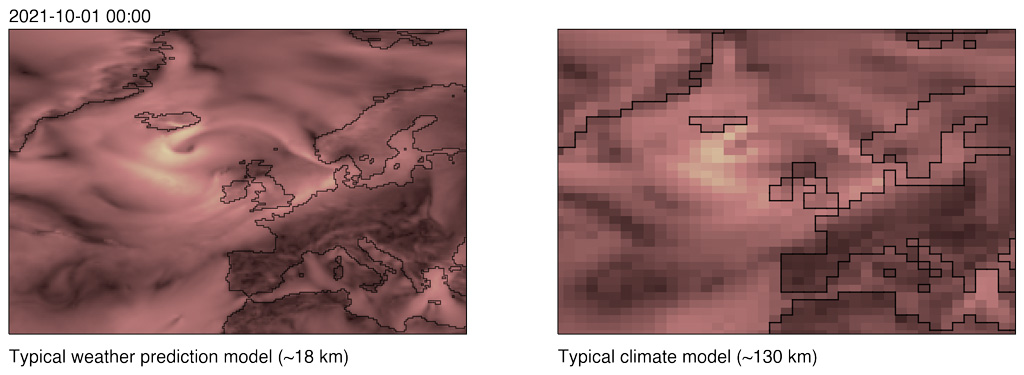

For example, all weather and climate models divide up the Earth’s surface and overlying atmosphere into a giant grid. They then calculate climate variables – such as temperature, humidity and rainfall – for each grid cell. A NWP model is typically run at a much higher “resolution” – that is, it has more, smaller grid cells – allowing it to simulate processes that a climate model cannot. You can see the extra detail in the illustrations below of a typical NWP model (left) and climate model (right) showing Europe and the North Atlantic.

Figure comparing the resolution in a typical weather prediction model (left) and climate model (right). This illustrative figure shows the same image scaled to the typical resolutions of weather and climate models. Credit: Nicholas J. Leach

“Nesting” higher-resolution regional models into global climate models is widely used in attribution studies, but cannot address biases in the simulation of large-scale atmospheric flow regimes resulting from inadequate global resolution.

Even a small reduction in resolution often changes the representation of extreme events in numerical models. The additional complexity of NWP models means they have the potential to be more suitable for studying the most extreme events than conventional climate models.

One example of this is the Pacific Northwest heatwave at the end of June this year. Many climate models appear to struggle to simulate events of a similar magnitude – even under significantly higher warming levels. However, the event was successfully predicted by several weather forecast centres around a week ahead. This suggests the NWP models used by these centres evidently do not share the same issues that many climate models appear to have in representing an event of this magnitude.

The next crucial aspect of using weather forecasts is that, since they are run in order to predict the weather, it is easy to demonstrate whether an NWP model is able to capture the processes required to credibly simulate a particular extreme event. Put simply, if they successfully predicted the event then they clearly can capture the processes necessary.

Since climate models are not run in order to simulate a single event, demonstrating the same in a climate model is considerably trickier. Being able to accurately represent the event we are interested in means that we can have more confidence in using the model to examine the impacts of the human influences on it.

In addition, the fact that successful weather forecasts produce simulations of a single specific event mean that we can unequivocally claim to be performing an attribution of the actual sequence of physical events that occurred. In climate models, it is necessary to analyse a mixture of different extreme weather events that share a key feature – for example, that they all produced a heatwave – but the reasons behind why they were extreme could be very different.

There is also a practical argument for using NWP models for attribution – they are run routinely at most weather forecast centres, typically at an hourly or other sub-daily time step. This means that if the scientific community were able to produce a forecast-based attribution methodology that weather forecast centres could implement relatively easily and at a low cost, it could pave the way for an operational attribution system that would be able to provide answers extremely rapidly after the event has occurred – and potentially even before.

European winter heatwave of 2019

As a case study, we tested our approach by assessing the contribution of a specific component of human influence on a winter heatwave that hit Europe in 2019.

Towards the end of February 2019, much of northern and central Europe experienced record-breaking winter temperatures. In particular, the UK observed multiple instances of winter temperatures exceeding 20C, culminating in a new record high temperature for a winter month when 21.2C was recorded at Kew Gardens in London (pdf).

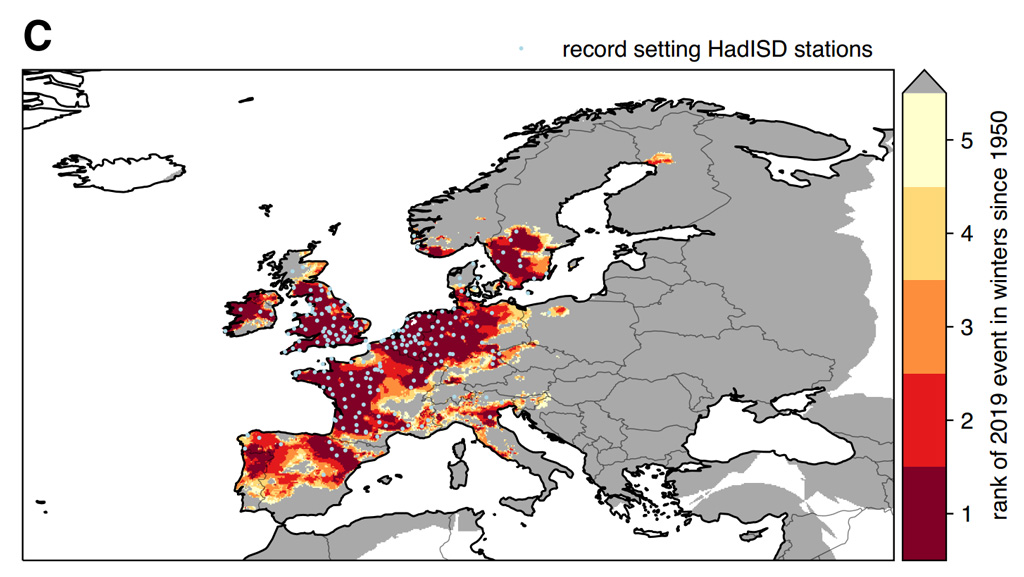

The map below shows how maximum temperatures across Europe during the 2019 heatwave ranked in comparison to all winters since 1950. The darkest red shading indicates locations where a new winter record was set.

Map showing how the maximum temperatures during the 2019 heatwave ranked out of annual maximum temperatures seen in winter. The dark red shading indicates locations where the 2019 heatwave (25 to 27 February 2019) saw the hottest winter temperature since at least 1950. Source: Leach et al. (2021)

Despite the exceptional nature of the heatwave – it was quantified by one study as being expected to occur less than once every 1,161 years in the present climate – it was extremely well predicted by the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts around 10 days before it happened.

Within the same NWP model that produced those successful predictions, we reduced the CO2 concentrations back to pre-industrial levels in order to assess what impact this would have on the heatwave. We assume pre-industrial global CO2 concentrations of 285 parts per million (ppm), which compares to around 410ppm in 2019.

There is a key point to note about this experiment design – we are not measuring the complete impact of human influence on the heatwave, just one component of it: the direct warming effect of the additional CO2 in the atmosphere over the forecast lead time.

Although the extra CO2 is a key part of the human contribution to the event, it does not take into account the long-term impact that higher CO2 levels are having on the planet – such as warmer oceans and reduced Arctic sea ice.

In effect, our model simulations of the February 2019 heatwave assume that CO2 levels had dropped to 285ppm the instant the simulation begins. As our forecasts are just days or weeks in length, the atmosphere has only just started to adjust to the dramatic change in CO2 levels. Therefore, the results we obtain for the direct impact of CO2 on the heatwave very much represent a lower bound on the actual impact.

Nonetheless, we found that the direct impact of CO2 had an unexpectedly rapid impact on the heatwave in our forecasts. Even where they started only three days before the heatwave, reducing the CO2 concentrations back to pre-industrial levels made it measurably less intense.

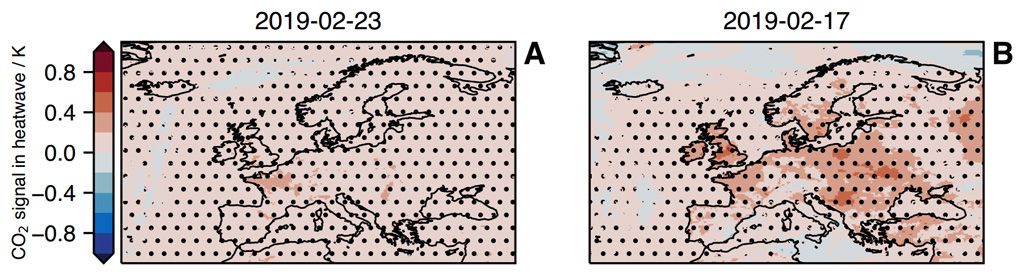

You can see this in the maps below, which show the warming influence (red shading) of the additional CO2 during the heatwave in forecasts initialised three days (left) and nine days (right) before the event.

Maps highlighting the direct impact of CO2 on the 2019 European winter heatwave. The left panel shows the attributed impact found using a forecast initialised just three days before the heatwave, and the right using a forecast initialised nine days before. The red shading indicates a warming impact from the additional CO2. Source: Leach et al. (2021)

In order to ensure that our findings were not due to the chaotic nature of the weather – that our perturbations were not simply resulting in different weather being forecast – we also ran an experiment with increased CO2 concentrations of 600ppm, and found that this had the opposite effect.

Overall, we found that reducing CO2 concentrations back to pre-industrial levels reduced the peak of the heatwave by around 0.4C, based on a forecast initialised nine days before the heatwave. Although this is not a huge amount, it is worth restating that this is only one component of the human contribution to the heatwave and so should be considered a very conservative estimate.

Nonetheless, the 0.4C difference would have been enough that significantly fewer temperature records would have been broken during the spell of hot weather.

In addition to being more severe, human-caused CO2 also made the event more likely. In the British Isles, for example, the direct CO2 effect increased the probability of the unseasonable heat in the weather forecast by 42%. For France, it is at least 100%.

What’s next?

Our work so far represents just the first few steps towards an operational forecast-based attribution system.

Our next aim is to try and provide a more complete estimate of the total human contribution to an extreme weather event. In order to do this, we are going to estimate what the initial state that the model starts in would look like without any human influence on the climate.

This will require us to both cool the oceans and make changes to the amount of sea ice to reproduce a more accurate reflection of what the world would like without global warming.

If we begin the weather forecast model from this state without human influence and reduce CO2 concentrations back to pre-industrial levels, then we might be able to create a picture of what this same extreme weather event would have looked like if it had occurred before any human-caused greenhouse gas emissions.

Nicholas J. Leach is a PhD candidate on the Environmental Research Doctoral Training Partnership at the University of Oxford.

Dr Antje Weisheimer is senior research fellow of the National Centre for Atmospheric Science (NCAS) and a co-leader of the Predictability of Weather and Climate group at the University of Oxford.

Prof Myles R. Allen is professor of geosystem science at the University of Oxford and director of the Oxford Net-Zero initiative.

Prof Tim Palmer is Royal Society research professor in climate physics, co-director of the Oxford Martin Programme on Modelling and Predicting Climate and a professorial fellow of Jesus College, Oxford.

Leach, N. J. et al. (2021) Forecast-based attribution of a winter heatwave within the limit of predictability, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, doi:10.1073/pnas.2112087118

Arguments

Arguments

Isn't attribution of individual extreme weather events more of a psychological pursuit than actual science? I mean, climate is an aggregated construct that is not unlike a baseball batting average, i.e. a statistical cumulative creation designed not to predict weather, but to evaluate what past activities show us and to tease out trends, correct? For a baseball player, if he starts injecting steroids into his body, all things being equal, his batting average or the number of homeruns may jump.

Now it is the steroids which caused the change, just as a jump in the amount of greenhouses in the atmosphere has caused an increase in extreme weather events that cumulatively changes the climate, right? But it seems to me that just as it is questionable science to try to tease out how much those steroids added to that last individual baseball hit compared to that player hitting that ball before he started taking steroids, the same pursuit with individual extreme weather events seems to be confusing the cumulative indicator with the observed data point. In other words, did the increased batting average cause the baseball player to hit that ball further, or was it the steroids? To conflate the two is a psychological pursuit, not a scientific one in my mind.

WDC, you're splitting hair.

It is a little ironic, since another, even more intense, winter heatwave has just hit Western Europe again.

A warming climate is predicted to lead to an increased frequency of extreme weather events. The climate is warming, and an increased frequency of extreme weather events is observed.

Going into the subtleties of: "this event was x times more likely to reach the extent that it did in a warming climate, but can not definitely be said to have done so because of it," may have merit, but is beyond the comprehension of the vast majority of the general public, who have no concept about differential probabilities. They can hardly even wrap their mind around probabilities at all, and are stunted in their quantitative thinking in general, as has been showed by the recent waves of denial and incomprehension associated with the pandemic.

Meanwhile, there is this: https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/billions/time-series

wilddouglascounty @1,

I'm not familiar enough with the game of baseball to discuss a "last individual baseball hit" but if this were the game of cricket, the analogy of an increased incidence of extreme weather would perhaps be analogous to a batsman hitting more sixes which would be a contribution to an overall increase in the steroid-taking batsman's batting average, the overall increase being analogous to the changing climate.

So in the analogy we can see the batting average increasing with the steroid-taking and we can see within that performance, the rise in the number of almost-sixes, the rise in actual sixes and the times now in which the ball sails clean out of the stadium. A statisitcal assessment can thus be made.

Note that your posed question "Did the increased batting average cause the (baseball) player to hit that ball further, or was it the steroids?" was answered by you within your analogy as you say "Now it is the steroids which caused the change, just as a jump in the amount of greenhouses in the atmosphere has caused an increase in extreme weather events that cumulatively changes the climate, right?"

Phillipe, MA Roger,

Sorry for not being more clear: what I am saying is that just as the conversation in athletics is about how steroid use impacts the batting average/number of sixes, instead of focusing on the nonsensical statement that that last hit can be attributed to an increased batting average, science should be focusing more on the physical impact of greenhouse gases than on what fraction of an event can be attributed to "climate change."

Climate is a statistical abstraction that can be summarized in all kinds of ways, whereas the roll of greenhouse gases in changing the atmospheric chemistry and its heat retention properties is a physical process that can be addressed by science. In other words "climate change" does not CAUSE more extreme weather events: a changed atmospheric chemistry does, and climate indicators are proof of those impacts CAUSED by greenhouse gases. Hope this helps.

I think I see the point wilddouglas country is making about attribution studies. Its something I have also wondered about. The term attribition is defined in online dictionaries as "the action of regarding something as being caused by a person or thing." However climate attribution studies do not really say that specific weather events are caused by a warming climate. They typically find that the event is exceedingly unlikely to have happened but for climate change. Not questioning this finding, but the term attribution just doesn't seem accurate. Climate influence studies would be more accurate.

The way I think of it is that a "weather event" is not really a single item. A heat wave is a higher-than-something temperature, and it carries with it an area of coverage and a length of time. It can be unusual or unexpected if it exceeds previous high temperatures, or if it covers a larger area than normal, or lasts longer than normal.

And "normal" itself has a geographical characteristic - temperatures that are normal in one place (and one time of year) may not be "normal" in another location or time of year.

All components of that "heat wave" may be subject to the effects of a globally warmer climate. "Attribution" needs to look at all aspects of that "event", and assess the probability that it would have happened in a climate that has not warmed.

For a simpler example, what about flooding? Let's say that a region has planned and built for river flooding up to 10 m above normal water levels. This has protected the region for decades, but then under a warmer climate there is heavier rainfall, and an 11 m flood overtops the protection and the region is flooded.

We can ask, "which metre of flood water caused the protection to fail? There are several possible answers, all of which could be argued with at least some success:

So, in this case, I think we can safely say that the 11 m flood was the result of climate change (precipitation in the thought experiment). But we still need to accept that something unusual might have happened without climate change, so the attribution is done on the basis of probabilities. We're 99% sure that the flood would not have happened if it were not for climate change.

...and I think that an essential part of the climate change message is pointing out that we are already seeing the effects. It is not a feature of the imagined future - it is now.

wilddouglascounty @4,

Thank you for the added clarity but I feel you are still attempting to paper over the idea that extreme weather will be worse under AGW and that will bring with it serious problems for humanity. (Of course, the sporting analogy breaks down here.)

You appear to be saying that the science should restrict itself to study of the physics of "the roll of greenhouse gases in changing the atmospheric chemistry and its heat retention properties." You say "science should be focusing more on the physical impact of greenhouse gases than on what fraction of an event can be attributed to climate change."

So AGW should be understood soley as, what, causing an increase in average global surface temperature of a degree or so, or more? Or perhaps even global averages are too statistical to have any meaning in the real world where AGW can even result in regional cooling. And sea level rise too. That may seen a solid physics thing but outside a few amphidromic points it is still dwarfed by the tidal range and requires weather to drive tidal surges.

Weather is a series of events and climate is a measure of what weather events can be expected. The science of climatology attempts to unravel the whats and the whys of weather stuff that together comprise climate. If climate changes so will the weather we can expect.

Yet you appear to be wanting to ignore the impacts of AGW, of say, 100-year events happening every year (on average) and even unprecidented 10,000-year events potentially now happening because it is not CO2 that directly causes these events as they are caused more correctly due to the effect of the atmospheric warming resulting from higher CO2 concentrations which in turn cause, say, on average deeper cyclones at higher latitudes which in turn occasionally drives far greater volumes of atmospheric H2O to suddenly rain-out over places where it will cause flash flooding that destroys buildings and forests and communities that have been happily standing for centuries and which would be a complete disaster if there happens to be an 'r' in the month; all of which is a "statistical abstration" which we shouldn't be bothering ourselves with.

MA Rodger,

Thanks so much for voicing your concerns, which I can assure you are completely unfounded. You say you feel that I am attempting to paper over the idea that extreme weather will be worse with AGW and cause increasing problems for humanity, but your concerns are completely unfounded. Nowhere do I imply this and I'm sorry you draw this conclusion from my stating and restating that my concern is that people are being inaccurate by saying that the statistical construct we've created to monitor the impact of greenhouse gases, i.e. "climate change" is CAUSING the observed changes (more severe, frequent extreme weather events, sea level rise, acidification, etc.). It is the greenhouse gases that are CAUSING the climate to change, the rising sea levels, the acidification, etc. Climate change is merely a constructed indicator that we use to communicate the impact of increased greenhouse gases in the atmosphere (and oceans, for acidification's sake). The only way to reduce and reverse AGW is to reduce the greenhouse gases being emitted to a level that the carbon sinks on our planet can absorb in order to return to an equilibrium that results in a climate we have become accustomed to.

In other words, when talking about attribution, instead of saying that a drought's severity is increased X percent due to climate change, I would like to see folks say that the drought's severity is increased X percent due to a 40% increase in CO2 in the atmosphere or whatever mix of all greenhouse gases you want to choose.

wilddouglascounty @8,

This interchange becomes perplexing.

I expressed the situation as I saw it @7 saying "I feel you are still attempting to paper over the idea that extreme weather will be worse under AGW and that will bring with it serious problems for humanity," believing you were happy that AGW resulted from increased GHGs in the atmosphere but that you had objection to the "statistical abstration" involved with the assessment of AGWs influence on extreme weather events.

But @8 you say I am wrong in this interpretation of your position.

It appears now that you are attempting to paper over the concept of "climate change" or AGW as you want the term "climate change" replaced by the rather lengthy phrase "a 40% increase in CO2 in the atmosphere or whatever mix of all greenhouse gases you want to choose." You even @8 describe "climate change" as being a"statistical construct we've created to monitor the impact of greenhouse gases" while @4 it is "climate" you describe as being "a statistical abstraction."

So is it simply use of the terms "climate change" and "AGW" or even use of the term "climate" you are objecting to? And I would find an affirmative response "perplexing" given your opening line @1 and your final line @8.

I posted earlier, but it did not show up, so am briefly posting one more time: In a nutshell, I have no objections whatsoever with any of the terms: climate, climate change and Anthropogenic Global Warming. I fully support them as valid concepts and useful measures of the impacts that have resulted from increasing the amount of greenhouse gases residing in our atmosphere.

My one and only point is that those composite measures are statistical abstractions that measure the impact of greenhouse gases, and there is a tendency to reify them by saying that the measures are causing the observed changes, when it in actuality is the greenhouse gas composition of the atmosphere that is the causal force. So for clarity's sake it is much better to refer to greenhouse gases as the reason that a storm event is more severe and occurring more frequently, not the tool of measurement, i.e. "climate change." If you want to attribute the increased frequency and increased amount of energy, I think it is worth pointing to the fact that there has been an increase of 47% in the composite greenhouse gas index since 1990 (AGGI index increasing to 1.47 since 1990) as the cause for the observed phenonenon. I hope this clarifies this once and for all, but feel free to agree/disagree/clarify as you see fit.

If I can butt in, hopefully without adding more confusion, I think what wilddouglascounty is saying is something that Dave Roberts said 10 years ago in a Grist post about the "semantic debate" involved whenever the issue of climate change attribution comes up. He even uses the example of steroids in baseball causing more home runs. I think this paragraph probably sums up wilddouglascounty's viewpoint:

Wilddouglascounty, please correct me if I am putting words in your mouth.

As a civil/structural engineer I have a different perspective regarding the debate about the merits of attribution analysis of extreme weather.

Civil designs, especially water run-off collection systems, and structures need to be designed to withstand 'weather extremes'. The rapid changes of weather extremes due to human action causing global warming and resulting climate change is critically important work.

It is inevitable that more frequent and more severe extreme events will be attributed to the human impacts. We have to hope that our designed systems are designed to perform successfully under the more extreme conditions, and fix already built stuff that isn't up to the challenge because it wasn't anticipated to need to be.

The science that anticipates the attribution of more extreme weather impacts is critical to the success/survival of what we build.

There are some people that suggest that saying "climate change is causing changes in the severity of the weather" is a misnomer, because climate change is in fact changes in the severity of the weather (eg: more intense or frequent droughts or storms).

They say we should really say that global warming or increasing greenhouse gas concentrations are causing changes in the weather. I think its all a bit pedantic. I don't think anyone is really confused as to what is causing changes in the weather. OPOF's comment seems more pertinent.

#11 David Kirtley,

Thank you for referring me to the Grist post, which I had not read before. Yes, Mr. Roberts accurately captures the inherent difficulties in trying to create causal distinctions between different parts of one atmosphere. The point I was making can best be outlined in his article by quoting his steroid example:

"When the public asks, “Did climate change cause this?” they are asking a confused question. It’s like asking, “Did steroids cause the home run Barry Bonds hit on May 12, 2006?” There’s no way to know whether Bonds would have hit the home run without steroids. But who cares? Steroids mean more home runs. That’s what matters."

I just wish Mr. Roberts had gone on to say that while "climate change" is a compilation or measure of the severity and frequency of weather episodes, it is greenhouse gases in the atmosphere that are causing it to change. It is best to say that increased greenhouse gases mean more extreme weather events. That's what matters.

Wilddouglascounty ~ so far in this discussion, my mind has not been subtle enough to discern the effect of the distinction, or difference, that you draw between the concept of global warming vs increased greenhouse gasses in the atmosphere.

To clarify your position: how would you describe the distinction (regarding increase in extreme weather events) in the - strictly hypothetical - case that the current rapid global warming were instead being caused by an ongoing rise in total solar irradiation?

Admittedly there is the crucial difference that such global warming would be beyond direct human intervention in its causation ~ but otherwise the nett effects would mimic AGW. But how would one (i.e. you) draw distinctions in the wording of attribution? And why so?

Because of the perspective I presented @12 I appreciate that the ways that the changes of climate will affect developed food production are more significant concerns regarding the attribution of human causes to climate change.

Every regional developed food production system is at risk, and needs to attempt to adapt to the changes if the regional climate changes (with no guarantees that the climate changes will support continued food production). And the more significant, and more rapidly, the regional climate changes occur the more harm is done to the global developed food production system. Sustainable total global food production, and systems developed to ensure that every human gets at least basic decent nutrition, is the measure that matters. The studies I have seen indicate that, globally, any regional positives of global warming are outweighed by regional negatives. And until the human impacts causing rapid climate change are actually ended, or are clearly on track to being ended, it is hard to know what future climate conditions food producers and distributors will need to try to adapt to.

Not knowing if the peak climate impact will be 1.5C, 2.0C, 2.5C, 3.0C, 3.5C means there is no way to plan new developments or revise existing developments for the demands of the future. But what is known is that the future of humanity is more damaged by more warming.

Attribution of climate change impacts to actual events that are seen to be harmful is essential to help convince the fence-sitting pragmatic moderates that it is harmful to compromise or ‘balance’ the understanding of the need to end harm done by human pursuits of benefit with the desires of people who want to benefit from continuing or expanding understandably harmful unsustainable actions.

15 Eclectic:

Global warming is a measurement that tracks one effect of an increased amount of greenhouse gases present in the atmosphere. The reason it is always important to take causality back to greenhouse gases is for the same reason we take the cause of an enhanced performance back to the ingested steroids instead of attributing that enhanced performance to the improved statistics that that performer has now.

If it were increased solar activity that was warming the planet say 1.5 degrees Celsius, you would have to look at the physics of the increased radiative output of the sun, just we look at the physics of increased heat retention provided by greenhouse gases, and calculate how the sun, not greenhouse gases or other components of the energy balance created the net increase.

We know quite a bit about the physics of solar irradiation and its warming component in the energy balance equation, just as we know quite a bit about the physics of greenhouse gas heat retention in that same equation, right? Both could cause the exact same amount of global warming, but the physics of both, being different and testable, are distinguishable, which is why we have concluded that the GW should have an "A" in front of it, not an "S" right?

Wilddouglascounty, thanks for your comment. No, I wasn't wishing in any way to imply that the current rapid global warming has a component of raised TSI ~ the evidence is quite clear that it doesn't.

I was interested in how you would choose to discuss the "attribution" of weather events, when talking with a layman ( 99% of the population - including politicians). You seem keen to use the phrasing which specifies the underlying cause ( CO2/greenhouse). Fair enough, mentioned once in a conversation. Yet I suspect your audience would soon tire of the repetition of a six-word phrase, when the two-word phrase ("global warming" or even vaguer: "climate change") conveys essentially the same message.

"Global warming" and "climate change" are terms now bandied about, throughout the media, and very frequently. People are used to hearing it, as a concept. Apart from Denialists, and people who are simply not interested in the topic ~ most people will know what you are talking about (and know the cause, as specified by scientists & science reporters). And that is why I am unclear why you wish to make use of "a distinction without a difference". Or perhaps better described as ~ a distinction which is unimportant to the man in the street.

That is where I am missing the subtlety of your message here.

The problem I have with the "it's not climate change, it's greenhouse gases" narrative is that the chain of causality never ends. And at each step of the chain, the contrarians will come up with an excuse to ignore it.

After "it's greenhouse gases", the contrarians wll come up with one of the following bogus arguments:

Once you successfully argue that it is CO2, then you get

and then if you manage to establish that the rise in CO2 is due to burning fossil fuels, you get all the "it's not bad", "technology will save us", "you'll hurt the poor", etc arguments.

There are many such arguments on the Skeptical Science "Arguments" page. I have only linked to a few.

What Bob Loblaw presents in his comment @19 is consistent with the evidence. It is independently verifiable understanding.

Building on Bob's points, admittedly triggered by him correctly pointing out the annoying claims some people make that the required changes to limit the harm done to the future of humanity (the rapid ending of fossil fuel use and other changes of developed activity) “will hurt the poor today”, there are many other harmful unsustainable developed human activities and unjust claimed excuses for them, not only the ones that can be connected to the harm done by human activity that increases CO2 levels.

That leads to an understanding based on the evidence (still open to improvement):

Actions, like attempts to end poverty, that depend on harmful unsustainable activity are not helpful, but will be developed by people who believe they will benefit from their development. And their helpfulness, especially their limiting of harm done, will be limited to what they believe they need to do to avoid personally suffering a lose of perceptions of status. They will continue to benefit from being harmful if they can get away with it. Their 'helpful' actions are harmfully unsustainable regardless of perceptions of helpfulness. Also, developed perceptions of enjoyment or superiority, or the opportunity for continued or increased perceptions of enjoyment and superiority, from understandably harmful developed systems and actions makes it harder to get people to unlearn, and resist liking, beliefs and claims that are developed to excuse harmful unsustainable developments they developed a liking for potentially benefiting from.

In comment #12, OPOF mentions civil design aspects of dealing with severe weather.

I'm pretty sure that every jurisdiction with design rules has some that are specific to climate/weather. In Canada, the Meteorological Service publishes "Engineering Climate Datasets".

There is a limitation to these data sets - they are based on historic data, not future climate.

If you want to build something today, for use over the next 30, 50, or 100 years, you will have an added burden of determining proper design limits based on future weather.

Bob Loblaw @21,

Indeed, the Canadian Building Codes include regional climate design requirement extremes (like snow, wind, rain, temperatures) based on the Climate Normals and Averages that Environment Canada updates every 10 years (EC has not yet published the 1991-2020 data). And design requirements like the Canadian Building Code are written as if they establish design requirements that will be adequate for the potential extreme weather conditions that would potentially impact a structure or system that is being built to last an established number of years like 50 or 100 years. But the rate of climate change and uncertainties of future climate make a difference to design requirements that is hard to establish.

What you have pointed out is indeed a challenge for designing things to successfully deal with the potential future climate conditions in any region. The Building Code only establishes “minimum design requirements to be met”. Everyone is free to design for more extreme requirements but, as I mention @16, without knowing how quickly the human impacts causing climate change will ‘change the climate’, and without knowing the expected peak level of impact, it is a bit of a fool’s errand to try to establish a regional design basis that would be sufficient to withstand conditions that may occur in the next 100 years, or even 50 years. Even if the regional climate forecasting could reasonably provide potential climate change results far enough into the future (like 100 years), knowing the peak human impact and how quickly it will be reached is required to establish appropriate design requirements.

Of course, absurdly severe design conditions could potentially be used. But who will establish what is ‘absurd enough’? And who will choose to impose the absurd requirements on what they ask to have designed and built, with the person making the request paying what it costs to get the result?.

And, as I mentioned @16, food producers have an even harder challenge attempting to plan their ‘adaptation to rapid human caused climate change’.

The conundrum of designing Civil and Structural systems for hard to predict (uncertain) rapid human-caused climate changes (and the potential absurdity of requests for that to be done) is what initially sparked my interest in learning more about this issue of “Rapid human caused Global Warming causing significant Climate Changes”.

With regard to desiging for weather/climate, this happens at the individual buliding scale (insulation levels, weight-bearing capacity for roof snow loads, solar heating rates to determine A/C capacity, etc.) and at the regional infrastructure scale (road drainage and frost-heave protection, storm sewer capacity, snow-clearing equipment capacity, etc.)

Getting it wrong can mean relatively manageable issues - higher operating costs (heating, cooling) - or catastrophic failures (roof collapse, bridge collapse, major flooding. loss of life).

Uncertainty is not our friend, and "that's someone else's problem, in the future" is not a very considerate point of view.

Overdesign costs money and is rarely noticed as a long-term problem. Underdesign makes the news, does undesirable things to an engineer's liabilty insurance premiums (or career), may end up in court, and may end up forever archived in Youtube videos.

#18 Eclectic,

Thank you again for your continued discussion, which on the whole has been much more extensive on this thread than I ever expected. I agree that "global warming" and "climate change" have become extremely recognizable in the media and the public around the world, and wanting to replace it with a mouthful of words with nearly the same meaning has questionable merit, so I understand why you are wondering why I want to shift it to what seems to be a subtle point which might be lost on most people. And you may be right.

But there are a couple of points I want to bring up for consideration. The first point is that do you remember when the phrase "global warming" was first popularized, the denialists got a lot of coverage whenever a greenhouse gas turbocharged polar vortex came barreling down from the arctic? Or when the north Atlantic cooling and salt dilution from all the ice melt from Greenland became a thing, potentially causing colder weather for northern Europe, as another example? The climatological community quickly realized that "global warming" did not adequately capture the complexity of changes that were occurring as a result of the changing atmospheric chemistry that were being observed. So "climate change" became the new replacement mantra, at least in the US community. This is an example of how popular terms are changeable, and made more accurate, thereby short circuiting misinformation in the process.

The second point to consider is how the use of steroids has played out in the sporting world. I've used baseball as an example, but steroid use clearly has had its impact across all sports as is evidenced in the Olympics Committee rules development and the increasingly complex monitoring of athletes across all sports. If the conversation in the sporting community just focused on homerun inflation, or increasing serving speeds in tennis, or other sports specific measures, then it would perhaps be harder to connect the dots to reveal the larger cause: steroid use. As we know, climate science has had to look at the much larger net of causality and relationships that impact and are impacted by the increase in the atmospheric greenhouse gas component. The ocean has increased CO2 absorption rates, resulting in acidification. The oceans themselves, not just the atmosphere, is warming, which contributes to sea level rise. The bottom line is that there are several monitoring indexes that are important to watch to understand the impact of greenhouse gas composition in the atmosphere. So just as the sporting community has focused on steroid use as the source of the myriad changes occurring in the sporting community, it makes sense to me to focusing on the source of ocean acidification, sea level rise relating to ocean water temperature, etc. AND climate change: greenhouse gases. It leaves the conversation about whether humanity is causing the problem behind us so we can move ahead with the next steps.

Thanks again for persisting, and I hope that this clarifies why I think it is worth considering this.

wilddouglascounty @ 24:

It is worth noting that "They changed the name from 'global warming' to 'climate change" is #90 on the SkS list of "Global Warming and Climate Change Myths".

Bob @23,

The lack of certainty of how to design things for the future climate is a serious problem. Not having 'adequate certainty' regarding what needs to be adapted to is the real problem, more so for food production than for things like structures or drainage systems. And a related problem is that the people benefiting from compromising the certainty of future climate conditions face very little potential for personal negative consequences.

If a designed and built item fails, or other harm is done, there can be legal and image problems for anyone directly involved like the engineer. But the people who push for things to be quicker, less expensive, more harmful or more likely to be harmful (pursuers of maximized personal benefit) can be very hard to penalize.

Demands for things to be more popular and profitable leads to things being done quicker and cheaper, which leads to pressure for more harmful and riskier things to be done, especially if Others will likely suffer any negative consequences.

A root of the problem is the lack of effective penalty for people who benefit from harmful activity. Their defence is typically a lack of proof that what they benefit from is unjust or harmful. They also raise doubt about the proof of their harmfulness. They will try to limit the emergence of evidence and improved understanding. They also demand that the "certainty of proof that they are being harmful" must be absolute. And they also raise doubt about being harmful by claiming Others are also, or are more, harmful.

And in a system governed by public opinion, like the competition for superiority based on popularity and profitability, it can be easy to get support for misunderstanding 'what and who is harmful', especially when there is ample evidence of the ability to get away with benefiting from being more harmful, especially if the benefit is being obtained at the risk of harm to Others.

A root understanding of ethics is "Do No Harm". Games played to determine who gets to benefit from 'Harm or Risk of Harm Done to Others' are ultimately unsustainable. The popularity and profitability of getting away with being harmful is able to powerfully compromise leadership actions almost everywhere. That type of game playing, or pragmatic or moderate balancing of interests, has no sustainable future. But a lot of harm can be caused before leadership is forced to prioritize effective actions to limit the understandable harm being done.

Wilddouglascounty , your analogy with steroids is a good one. (Though technically an athlete can achieve "steroid performance" via scientific strength-training ~ it just takes a little longer and requires more willpower.) And apart from Thatcher, our politicians tend to lead from behind . . . excepting for just their rhetoric, as shown in international conferences!

Bob Loblaw points out that the terms CC (Climate Change) and GW (Global Warming) have both been in use for many decades. CC from the 1950's and GW from the 1980's at least.

Always it comes back to what the public - the voters - perceive. They seem moderately happy to use the terms CC and GW in their thinking about the anthropogenic CO2 problem. I would worry that your proposal for using a third term might well be counter-productive, with some portion of the population being irritated by a sense of "constant revolution" in climate terminology.

Using a broad-brush classification, people can be divided into 4 categories :-

A/ the cognoscenti/activists, who see the AGW problem for what it is ~ regardless of terminologies used.

B/ the general public, who are moderately aware of the AGW issue, and who don't really care whether it's called CC or GW.

C/ those who, while not actively hostile to broad socioeconomic changes required in solving the AGW problem ~ are nevertheless a bit reluctant to suffer mild inconvenience, or who feel unease about prospective changes. And they also don't care whether it is called CC or GW.

D/ the Denialists, who oppose anything and everything AGW-related. They do definitely care about the terminology used ~ and they tend to froth at the mouth at any flip-flop in terms used, and they create strawman arguments regarding "the science obviously not being settled". (Among other things.)

For my sins, I often look through the articles and comments at the WattsUpWithThat blogsite. (It doesn't take long to skim through the day's effusions, provided that you only pause to read comments - and immediate replies to - the handful of commenters who are scientifically well-informed and intellectually sane.)

Sadly, the great generality of WUWT commenters are like a group of tetchy backyard dogs. They launch into prolonged barking at even the slightest disturbance ~ at someone's door closing; at a pedestrian walking by; at a bird chirping in a tree; at a vehicle going past. Perhaps they like barking, or they are hungry, or their emotional needs are not being met.

Eclectic,

I appreciate your patient discussion of the topic, which I believe has met its desired level of mutual understanding. I think you understand my desire for folks to use the term "greenhouse gases" or the related phrases: "changes in the chemistry of the atmosphere linked to human activity," "anthropogenic greenhouse gases," "increased AGGI index," or any other term you want to choose, when trying to attribute the causes of a particular extreme weather event, or trends for that matter. For clarity's sake, it leads to a cleaner understanding of the causes of the observed changes, in the same way as pointing to steroid use is a cleaner understanding of the causes of changed performance patterns in sports. It is also more encompassing in that the change in greenhouse gases is linked to observed physical phenomena outside the realm of the earth's climate.

On my part, I have a renewed respect that the terms climate change, AGW and global warming are still useful terms, especially when they are used outside the discussion of causality. The observation that most years I cannot skate on ponds that I grew up skating on in the winter is one example of global warming that I can point to in my neck of the woods, just as peonies that were planted by my ancestors to bloom on Memorial Day at the end of May but now bloom weeks too early most years is another indication of a changing climate.

Regarding when terms first began to be used, I am not so interested in when they were first used so much as what terms are currently being used, which is increasingly climate change, as evidenced here: LINK

Personally I find climate change to be more inclusive so I'm fully supportive of using that phrase when talking about generalities, for the reason I've already stated. But I understand that this is a usage preference only, as any term is fraught with and susceptible to misuse and abuse. So thanks for the conversation and hopefully we have all gained something from the exercise.

[DB] Shortened link breaking page formatting.