Global warming and the El Niño Southern Oscillation

What the science says...

| Select a level... |

Basic

Basic

|

Intermediate

Intermediate

| |||

|

El Nino has no trend and so is not responsible for the trend of global warming. |

|||||

Climate Myth...

It's El Niño

"Three Australasian researchers have shown that natural forces are the dominant influence on climate, in a study just published in the highly-regarded Journal of Geophysical Research. According to this study little or none of the late 20th century global warming and cooling can be attributed to human activity. The close relationship between ENSO and global temperature, as described in the paper, leaves little room for any warming driven by human carbon dioxide emissions. The available data indicate that future global temperatures will continue to change primarily in response to ENSO cycling, volcanic activity and solar changes." (Climate Depot)

At a glance

This particular myth is distinguished by the online storm that it stirred up back in 2009. So what happened?

Three people got a paper published in the Journal of Geophysical Research. It was all about ENSO - the El Nino Southern Oscillation in the Pacific Ocean. ENSO has three modes, El Nino, neutral and La Nina. In El Nino, heat is transferred from the ocean to the atmosphere. In La Nina, the opposite happens. So within ENSO's different modes, energy is variously moved around through the planet's climate system, but heat is neither added nor subtracted from the whole. As such, in the long term, ENSO is climate-neutral but in the short term it makes a lot of noise.

The paper (link in further details) looked at aspects of ENSO and concluded that the oscillation is a "major contributor to variability and perhaps recent trends in global temperature". First point, sure. Second point, nope, if you accept climate trends are multidecadal things, which they are.

That might have been the end of it had the authors not gone full-megaphone on the media circuit, promoting the paper widely in a certain way. "No scientific justification exists for emissions regulation", they loudly crowed. "No global warming", the denizens of the echo-chamber automatically responded, all around the internet. This is how climate science denial works.

Conversely, the way that science itself works is that studies are submitted to journals, peer-reviewed, then some of them get published. Peer review is not infallible - some poor material can get through on occasion - but science is self-correcting. So other scientists active in that field will read the paper. They may either agree with its methods, data presentation and conclusions or they may disagree. If they disagree enough - such as finding a major error, they respond. That response goes to peer-review too and in this case that's exactly what happened. An error so fundamental was found that the response was published by the same journal. The error concerned one of the statistical methods that had been used, called linear detrending. If you apply this method to temperature data for six months of the Austral year from winter to summer (July-December), it cannot tell you that during that period there has been a seasonal warming trend. So what happens if you apply it to any other dataset? No warming! Bingo!

A response to the response, from the original authors, followed but was not accepted for publication, having failed peer-review. At this point, the authors of the rejected response-to-the-response started to screech, "CENSORSHIP" - and the usual blogosphere battles duly erupted.

It was not censorship. Dodgy statistical techniques were picked up by the paper's highly knowledgeable readership, some of whom joined forces to prepare a rebuttal that corrected the errors. The response of the original paper's authors to having their errors pointed out was so badly written that it was rejected. That's not censorship. It's about keeping garbage out of the scientific literature.

Quality control is what it's all about.

Please use this form to provide feedback about this new "At a glance" section. Read a more technical version below or dig deeper via the tabs above!

Further details

ENSO, the El Nino Southern Oscillation, is an irregular but well-understood phenomenon that affects the Eastern and Central Pacific Oceans. It is important both on a local and global basis, since it not only causes changes in sea-surface temperatures. It also affects the thermal profile of the ocean and both coastal and upwelling ocean currents.

Such changes can and do affect the diversity and abundance of important edible seafood species. Cold and warm-water forms are forced to migrate to where they find the conditions more to their liking. El Nino events in particular, where warm waters prevail close to the sea surface, can inflict a temporary loss of commercially important species of fish and squid from where they are traditionally fished. Some coastal communities along the Pacific seaboard of South America have a strong dependency on such fisheries. As such, prolonged El Nino conditions can be seriously problematic.

The warm El Nino mode of ENSO also affects global temperatures, as heat energy is transferred from ocean surface to the atmosphere. A strong El Nino is easily capable of raising temperatures above the upward slope that represents the change in radiative forcing caused by our increasingly vast greenhouse gas emissions - global warming, in other words. Conversely, the opposite to El Nino, La Nina, suppresses global temperatures. When several La Nina years occur in a row, climate science deniers are given the opportunity to insist that the world is cooling. This has happened before, most notably in the post-1998 period.

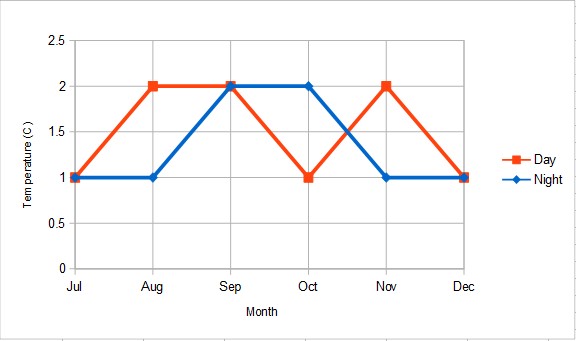

However, as fig. 1 shows, global temperature is rising independently of the short-term ENSO noise. Fig. 1 also shows that 2022 was the warmest La Nina year in the observational record. In fact, El Nino, La Nina and neutral years are all getting warmer.

Fig. 1: variations in ENSO in a warming world. This plot therefore shows two independent phenomena that affect climate: the noisy ENSO and the underlying relentless upward climb in temperatures caused by our rapidly-increasing emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases. Temperature records typically get broken in El Nino years because the temperature is given an extra boost. 2016, a major El Nino year, held the global temperature record for a few years, but 2023 saw that record fall again. 2023 is in grey because that El Nino did not develop until later in the year. Graphic: Reaclimate.

The reader should by now be in no doubt about the difference between the long term global temperature trend caused by increased greenhouse gas forcing and the noise that shorter-term wobbles like ENSO provide. You would have seen something similar during the descents into and climbs out of ice-ages too. That's because ENSO has likely been with us for a very long time indeed. Ever since the Pacific Ocean came close to its present day geography, millions of years ago, it has likely been there.

The reader should by now be in no doubt about the difference between the long term global temperature trend caused by increased greenhouse gas forcing and the noise that shorter-term wobbles like ENSO provide. You would have seen something similar during the descents into and climbs out of ice-ages too. That's because ENSO has likely been with us for a very long time indeed. Ever since the Pacific Ocean came close to its present day geography, millions of years ago, it has likely been there.

Nevertheless, here we have something that warms the planet, even if that's on a temporary basis. As a consequence, some people with ulterior motives might just become interested. Over a decade ago now, that's what happened. A paper, 'Influence of the Southern Oscillation on tropospheric temperature' (Mclean et al. 2009) was published in the Journal of Geophysical Research. One of its co-authors, a well-known climate contrarian, commented:

"The close relationship between ENSO and global temperature, as described in the paper, leaves little room for any warming driven by human carbon dioxide emissions."

If you enter the above quote, complete with its quotation marks, into a search engine, you will get lots of exact matches. Strange? Not really, if you have studied the techniques of climate science denial.

- a paper is published that barely mentions global warming.

- its authors go on to distribute slogans implying that they have put yet another Final Nail in the global warming coffin.

- right-wing media of all sorts from newspapers to blogs ensure wide distribution of the talking-points.

- individuals serve to fill in the circulation-gaps.

This is how it works, time and again. However, glaring errors were soon noticed in the paper, leading a group of specialists to offer a rebuttal, published in the same journal a year later (Foster et al. 2010).

Statistics is not everyone's cup of tea, but a very straightforward explanation of the key error was provided by Stephen Lewandowsky, writing at ABC (archived):

"This is best explained by an analogy involving daily temperature readings between, say, July and December anywhere in Australia. Suppose temperature is recorded twice daily, at midday and at midnight, for those 6 months. It is obvious what we would find: Most days would be hotter than nights and temperature would rise from winter to summer. Now suppose we change all monthly readings by subtracting them from those of the following month—we subtract July from August, August from September, and so on. This process is called "linear detrending" and it eliminates all equal increments. Days will still be hotter than nights, but the effects of season have been removed. No matter how hot it gets in summer, this detrended analysis would not and could not detect any linear change in monthly temperature."

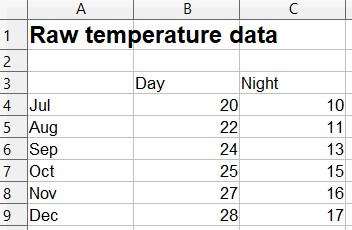

Anyone can do this in Excel. First input a series of representative temperatures for the transition from Austral winter into summer:

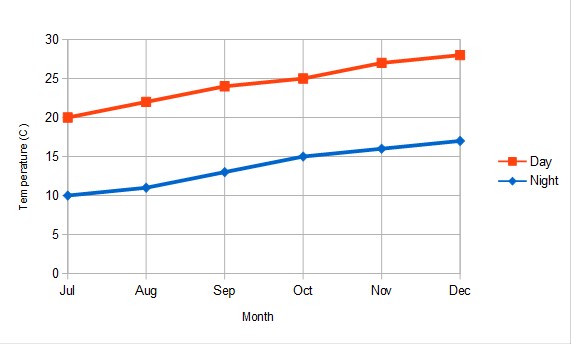

Reasonable? OK, then let's plot them. Still looks like what we'd expect. It gets warmer in Australia from July to December and nights are usually colder than days, right?

Now, let's do that detrending. This is what you get:

As Lewandowsky pointed out in his ABC article:

"Astonishingly, McLean and colleagues applied precisely this detrending to their temperature data. Their public statements are thus equivalent to denying the existence of summer and winter because days are hotter than nights."

In other words: Fail.

Last updated on 24 March 2024 by John Mason. View Archives

Arguments

Arguments

[Sph] The links cannot be fixed, only removed, as the external source documents have been removed from the Internet (and we have no control over that).

[DB] The Atmoz article is available here.

The Tamino article is available here, via the Open Mind Archives.

This link to the web archive is functional.

Coefficients: Estimate Std. Error t value Pr(>|t|) (Intercept) 9.130818 0.476369 19.168 <2e-16 *** sst$Nino34a -0.029659 0.003410 -8.699 <2e-16 *** sst$Nino34b 0.049365 0.003374 14.630 <2e-16 *** sst$Nino34c 0.034237 0.001911 17.920 <2e-16 *** sst$Year -0.004543 0.000238 -19.085 <2e-16 *** sst$aodlag -3.495310 0.095644 -36.545 <2e-16 *** --- Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1 Residual standard error: 0.06831 on 1555 degrees of freedom Multiple R-squared: 0.5086, Adjusted R-squared: 0.5071 F-statistic: 321.9 on 5 and 1555 DF, p-value: < 2.2e-16ν ≈ 11, so the t-values can be scaled down by a factor of 3.3, but they’re all hugely significant except lag(Nino34,0), which has a p-value of ~98%. R2 is now up to 0.5. That’s a model we can begin to draw conclusions from. What does it look like? See the following figure. Red is Rest, blue is the model, both with a 13 month smooth. We can still see a divergence around 1998-2001, although it doesn’t stand out like it did. However the 1989-1991 event has all but vanished. In eliminating the nuisance variables to obtain a better model whose parameters are therefore vastly more significant, one of the two events you identified has disappeared. That’s why I cautioned about the dangers of data-mining. When the model is poor it is far too easy to over-interpret the results.Tom Curtis, in your comment 80, you presented your findings about the significance (the lack thereof) of the lack of warming in the East Pacific sea surface temperature data versus the IPCC model hindcasts/projections. A recent post at Niche Modeling titled East Pacific Region Temperatures: Climate Models Fail Again found precisely the opposite, as you may have guessed from the title of the post.

michael sweet says at 122: My point is still valid, you must compare to the range of estimates, not the average.”

NCAR and Gavin Schmidt disagree with you.

The National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR)’s Geographic Information Systems (GIS) Climate Change Scenarios webpage has a relatively easy-to-read description. This quote appears on their Frequently Asked Questions webpage:

On the thread of the RealClimate post Decadal predictions, a visitor asked the very basic question, “If a single simulation is not a good predictor of reality how can the average of many simulations, each of which is a poor predictor of reality, be a better predictor, or indeed claim to have any residual of reality?”

Gavin Schmidt replied:

We’re interested in the forced component, michael, not the noise, hence my use of the multi-model ensemble mean.

michael sweet says: “Many other data sets exist that expand the time period of your analysis. It has been shown by others in this thread that you cherry picked the data set you used.”

I cherry-picked my dataset? Since I must have missed the comments you’re referring to, let me answer your and their comments now. Maybe you’re referring to a comment by IanC. I replied to him, Why aren’t we looking at the sea surface temperature data prior to the satellite era? Because there’s little source data south of 30-45S. Here’s a map that illustrates the ICOADS sampling locations six months before the start of the Reynolds OI.v2 dataset:

http://i47.tinypic.com/k2g6bs.jpg

Same map for June 1975:

http://i49.tinypic.com/73040z.jpg

And it doesn’t get better as you go back in time. Here’s June 1943:

http://i49.tinypic.com/2eb8sb8.jpg

And to further respond to your accusations of cherry-picking, michael sweet, are you aware that HADSST2 and HADSST3 are spatially incomplete during satellite era? Are you aware that NOAA’s ERSST.v3b has to be infilled during the satellite era because it does not use satellite data? Are you aware that Smith and Reynolds called the Reynolds OI.v2 dataset the “truth”? Refer to Smith and Reynolds (2004) Improved Extended Reconstruction of SST (1854-1997). It is about the Reynolds OI.v2 data we’ll be using as the primary source of data for this book:

The truth is a good thing, don’cha think?

KR says at 124: “If as you say La Nina's absorb more heat (due perhaps to changes in cloudiness or other effects) than El Nino releases, how can this have driven warming since the 1970's? There has been a preponderance of El Nino events over that period (fewer than average La Nina events to raise total climate energy, esp. late 1970's-1998).”

You need to look at surface temperature and ocean heat content separately, because they respond differently to ENSO.

Let’s discuss surface temperatures first:

KR, we agree on something. “There has been a preponderance of El Niño events over that period…” Glad you confirmed that ENSO has been skewed toward El Niño since the late 1970s. This means that more warm water than normal has been released from the tropical Pacific and redistributed, and it means that more heat than normal has been released to the atmosphere. That answers your question, “how can this have driven warming since the 1970's?”

Now let’s address the ocean heat content portion of your question: “If as you say La Nina's absorb more heat (due perhaps to changes in cloudiness or other effects) than El Nino releases…”

This makes itself known in the Ocean Heat Content for the tropical Pacific. The 1973-76 La Niña created the warm water that served as the initial fuel for the subsequent 1982/83 through the 1994/95 El Niño events, with the La Niña events that trailed those El Ninos replacing part of the warm water. That’s why the tropical Pacific OHC trend is negative from 1976 until the 1995/96 La Niña.

The 1995/96 La Niña was a freak, and discussed in McPhaden 1999. “Genesis and Evolution of the 1997-98 El Niño”.

http://www.pmel.noaa.gov/pubs/outstand/mcph2029/text.shtml

McPhaden writes:

In other words, there are parts of ENSO that cannot be accounted for with an ENSO index.

The impact of the 1995/96 La Niña stands out like a sore thumb in the graph of tropical Pacific OHC. Then, moving forward in time, there’s the dip and rebound associated with the 1997/98 El Niño and 1998-01 La Niña.

KR asks: “Why now? What has changed? The ENSO has been an existent pattern for perhaps hundreds of thousands of years. Why would it suddenly change behavior in recent years, when it hasn't in the past?”

Paleoclimatological studies find evidence of ENSO back millions of years ago—not just hundreds of thousands of years. See Watanabe et al (2011). Your second question (“Why would it suddenly change behavior in recent years, when it hasn't in the past?”) is an assumption on your part. El Niño events were also dominant during the early warming period of the 20th Century, and global temperatures warmed in response then, too.

KR asks: “Finally, what about the greenhouse effect?”

Downward longwave radiation appears to do nothing more cause a little more evaporation from the ocean surface, which makes perfect sense since it only penetrates the top few millimeters.

In response to KevinC comment at 131:

Thanks for your efforts. As you noted, it’s a great place to start a discussion. You seem to have created a great fit for the Mount Pinatubo eruption and the lesser ENSO events.

KevinC says: “However we now only have one event. You can’t fit a pattern to a single event.”

The 1997/98 El Niño was the strongest event and should have the cleanest signal, which makes your model versus Rest of the World graph look very awkward and unrealistic. (The fact that it should be the cleanest signal is why I keyed off the leading edge of the 1997/98 El Niño in my illustration.) Note how the other larger El Niño events in your model-data graph also don’t fit that well. If you would, please subtract the ROW data from your model to show how significant the residuals are.

Therefore, for a really detailed analysis you’re attempting to perform, where you’re keying off all events, it’s likely you’ll need to isolate the East Pacific El Niño events like the 1986/87/88 and 1997/98 events and their trailing La Niña events. Why? The global temperature response to East Pacific El Niños (large events) is different from Central Pacific El Ninos (lesser events). That was the basis for the Ashok et al (2007) paper El Niño Modoki and its Possible Teleconnection.

The reasons for the divergences in the Rest-Of-the-World data during the 1988/89 and 1998-2001 La Niñas are physical, KevinC. You can try to eliminate or minimize them using models, but they exist. East Pacific El Niños like the 1986/87/88 and 1997/98 El Niños release vast amounts of warm water from below the surface of the west Pacific Warm Pool. Much of that warm water spreads across the surface of the central and eastern tropical Pacific. For the East Pacific El Niño events, like those in 1986/87/88 and 1997/98, that warm water impacts the surface all the way to the coast of the Americas (while with Central Pacific El Niño events it does not). The El Niños do not “consume” all of the warm water. At the conclusion of an El Niño, the trade winds push the leftover warm surface water back to the West Pacific. Additionally, there is left over warm water below the surface that’s returned to the west Pacific and into the East Indian Ocean via a Rossby wave or Rossby waves. This animation captures a Rossby wave returning warm water to the West Pacific and East Indian Oceans after the 1997/98 El Niño. Watch what happens when it hits Indonesia. It’s like there’s a secondary El Niño taking place in the Western Tropical Pacific and it’s happening during the La Niña. It’s difficult to miss it. (The full JPL animation is here.) Gravity causes that warm water to rise to the surface with time. The leftover warm water exists and it cannot be accounted for with a statistical model based on an ENSO index. You can see—you can watch it happen—the impacts of that warm water in this animation. There are no ENSO indices that account for the leftover warm water.

John Hartz says at 123: “Please explain in one or two succinct paragraphs why you do not agree with the above statement.”

Easy to do. I’ll cut and paste my opening comment on this thread, where the East Pacific data agrees with the WMO Secretary-General Michel Jarraud’s quote, but the Rest-Of-The World data does not:

The East Pacific Ocean (90S-90N, 180-80W) has not warmed since the start of the satellite-based Reynolds OI.v2 sea surface temperature dataset, yet the multi-model mean of the CMIP3 (IPCC AR4) and CMIP5 (IPCC AR5) simulations of sea surface temperatures say, if they were warmed by anthropogenic forcings, they should have warmed approximately 0.42 to 0.44 deg C. Why hasn’t the East Pacific warmed?

The detrended sea surface temperature anomalies for the Rest of the World (90S-90N, 80W-180) diverge significantly from scaled NINO3.4 sea surface temperature anomalies in 4 places. Other than those four-multiyear periods, the detrended sea surface temperature anomalies for the Rest of the World mimic the scaled ENSO index. The first and third divergences are caused by the eruptions or El Chichon and Mount Pinatubo. Why does the detrended data diverge from the ENSO index during the 1988/89 and 1998/99/00/01 La Niñas? According to numerous peer-reviewed papers, surface temperatures respond proportionally to El Niño and La Niña events, but it’s obvious they do not.

IanC says at 120: “Seriously, do you see yourself being wrong on the issue? do you see a possibility that your analyses are wrong?”

IanC, with respect to my understanding of ENSO, I have investigated, discussed, illustrated, and animated the process of ENSO and its effects on global surface temperatures, ocean heat content and lower troposphere temperatures for almost 4 years. I have presented the effects of ENSO on sea surface temperature, sea level, ocean currents, ocean heat content, depth-averaged temperature, downward shortwave radiation, warm water volume, sea level pressure, cloud amount, precipitation, the strength and direction of the trade winds, etc. I have presented the multiyear aftereffects of ENSO on sea surface temperature, land-plus-sea surface temperature, lower troposphere temperature and ocean heat content data. I have created numerous animations. Everything I’ve investigated confirms my understanding of ENSO and its long-term effects.

ENSO is a process. It cannot be accounted for by an ENSO index. Compo and Sardeshmukh (2010) “Removing ENSO-Related Variations from the Climate Record” seems to be a step in the right direction. They write (my boldface):

Compo and Sardeshmukh have not accounted for the left over warm water associated with major El Niño events, like the 1986/87/88 and 1997/98 El Niños. In time, maybe they will.

At comment 107, Composer99 quoted one of my earlier comments: “Are you aware that the global oceans can be divided into logical subsets which show the ocean heat content warmed naturally?”

Composer99 replied, “No, they can't. Ocean heat has to come from somewhere.”

Apparently you have never divided OHC data into subsets, because if you had, you would not make such a statement. Dividing the oceans into subsets shows the ocean heat comes from somewhere, but it’s not CO2.

For the sake of discussion, I’m going to borrow some graphs from an upcoming post. Here’s a comparison graph of Global ocean heat content and the ocean heat content for the Pacific Ocean north of 24S, which captures the tropical Pacific and the extratropics of the North Pacific (24S-65N, 120E-80W). The Pacific OHC (North of 24S) shows similar but somewhat noisier warming. That is, the decadal variations are similar. The warm trend of the Pacific subset is about 72% of the global trend, but that’s to be expected since the excessive warming of the North Atlantic OHC skews the global data. All in all, both datasets give the impression of a long-term warming that’s somewhat continuous. People might assume the warmings of both datasets were caused by CO2.

We’re going to separate the tropical Pacific (24S-24N) from the extratropical North Pacific (25N-65N), looking at the tropical Pacific first, but that requires a brief overview of how La Niña events produce the warm water that fuel El Niño events.

El Niño and La Niña events are part of a coupled ocean-atmosphere process. Sea surface temperatures, trade winds, cloud cover, downward shortwave radiation (aka visible sunlight), ocean heat content, and subsurface ocean processes (upwelling, subsurface currents, thermocline depth, downwelling and upwelling Kelvin waves, etc.) all interact. They’re dependent on one another. During a La Nina, trade winds are stronger than normal. The stronger trade winds reduce cloud cover, which, in turn, allows more downward shortwave radiation to enter and warm the tropical Pacific.

If you’re having trouble with my explanation because it’s so simple, refer to Pavlakis et al (2008) paper “ENSO Surface Shortwave Radiation Forcing over the Tropical Pacific.” Note the inverse relationship between downward shortwave radiation and the sea surface temperature anomalies of the NINO3.4 region in their Figure 6. During El Niño events, warm water from the surface and below the surface of the West Pacific Warm Pool slosh east, so the sea surface temperatures of the NINO3.4 region warm, causing more evaporation and more clouds, which reduce downward shortwave radiation. During La Niña events, stronger trade winds cause more upwelling of cool water from below the surface of the eastern equatorial Pacific, so sea surface temperature to drop in the NINO3.4 region, in turn causing less evaporation. The stronger trade winds also push cloud cover farther to the west than normal. As a result of the reduced cloud cover, more downward shortwave radiation is allowed to enter and warm the tropical Pacific during La Niña events.

To complement that, here’s a graph to show the interrelationship between the sea surface temperature anomalies of the NINO3.4 region and cloud cover for the regions presented by Pavlakis et al.

That discussion explains why the long-term warming of the Ocean Heat Content for the tropical Pacific was caused by the 3-year La Nina events and the unusual 1995/96 La Niña. First, here’s a graph of tropical Pacific Ocean Heat Content. It’s color coded to isolate the data between and after the 3-year La Niña events of 1954-57, 1973-76 and 1998-2001. Those La Niña events are shown in red. Note how the ocean heat content there cools between the 3-year La Niña events. Anyone who understands ENSO would easily comprehend how and why that happens. It’s tough to claim that greenhouse gases have caused the warming of the tropical Pacific when the tropical Pacific cools for multidecadal periods between the 3-year La Niñas, Composer99.

As you can see, the warming that took place during the 1995/96 La Niña was freakish. Refer to McPhaden 1999 “Genesis and Evolution of the 1997-98 El Niño”.

McPhaden writes:

Based on the earlier description, that “build up of heat content” resulted from the interdependence of trade winds, cloud cover, downward shortwave radiation and ocean heat content. Simple. As you can see in the above graph, the upward spike caused by the 1995/96 La Niña skews the trend of the mid-cooling period, and if we eliminate the data associated with it and the 1997/98 El Niño, then the trend line for the mid-period falls into line with the others.

So far, there’s no apparent AGW signal.

Let’s move on to the extratropical North Pacific. That dataset cooled significantly from 1955 to 1988, more than 3 decades. Where’s the CO2 warming signal there, Composer99? Then in 1989 and 1990, there was an upward shift. It’s really tough to miss, because the North Pacific was cooling before the sudden 2-year warming and then it warmed after it. As you’ll note, the cooling trend before the shift is comparable to the warming trend after it. BUT, big but, the cooling period lasted for 34 years, while the warming period only lasted for 22 years. That means the North Pacific (north of 24N) would have cooled since 1955 if it wasn’t for that 2-year upward shift.

In summary, the ocean heat content data for the Pacific Ocean north of 24s (the initial graph) gives misleading impression of a relatively continuous warming; it’s misleading because, when the data is broken down into two logical subsets, tropics versus extratropics of the North Pacific, the data clearly shows that factors other than greenhouse gases were responsible for the warming.

I think Skywatcher's request deserves a non-evasive response (a link to an hour long video is hardly a response to a question).

I would suggest, for clarity, posting one comment for each question, and sticking to the question being addressed, to avoid any confusion. Please answer the questions directly and succinctly.