The Economist Screws Up on the Draft IPCC AR5 Report and Climate Sensitivity

Posted on 19 July 2013 by dana1981

Earlier today, The Economist published a piece of irresponsible journalism regarding information in the draft Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fifth Assessment Report (IPCC AR5). The Economist saved us some effort by explaining the problems with their own article:

“There are several caveats. The table comes from a draft version of the report, and could thus change. It was put together by the IPCC working group on mitigating climate change, rather than the group looking at physical sciences. It derives from a relatively simple model of the climate, rather than the big complex ones usually used by the IPCC. And the literature to back it up has not yet been published.”

So folks at The Economist, please explain to us, why are you reporting on climate sensitivity information in this draft report about climate mitigation that uses a simple climate model and is based on unpublished literature?

Readers may recall that climate contrarian blogs behaved in a similar fashion when the IPCC AR5 draft report on the physical science was “leaked” last December. The contrarians made a huge to-do about a figure that seemed to show global surface temperature measurements at the very low end of the IPCC model projections. As we discussed at the time, in reality the IPCC temperature projections have been very accurate. As Tamino noted, the draft IPCC graph itself was flawed, using a single year as the baseline (1990) rather than aligning the data and models based on the existing trend in 1990. Fast forward a few months later, and we hear from IPCC reviewers that this graph has been revised accordingly, now correctly reflecting the accuracy of the IPCC surface temperature projections. The lesson to be learned is that you shouldn’t report on draft documents that are subject to change!

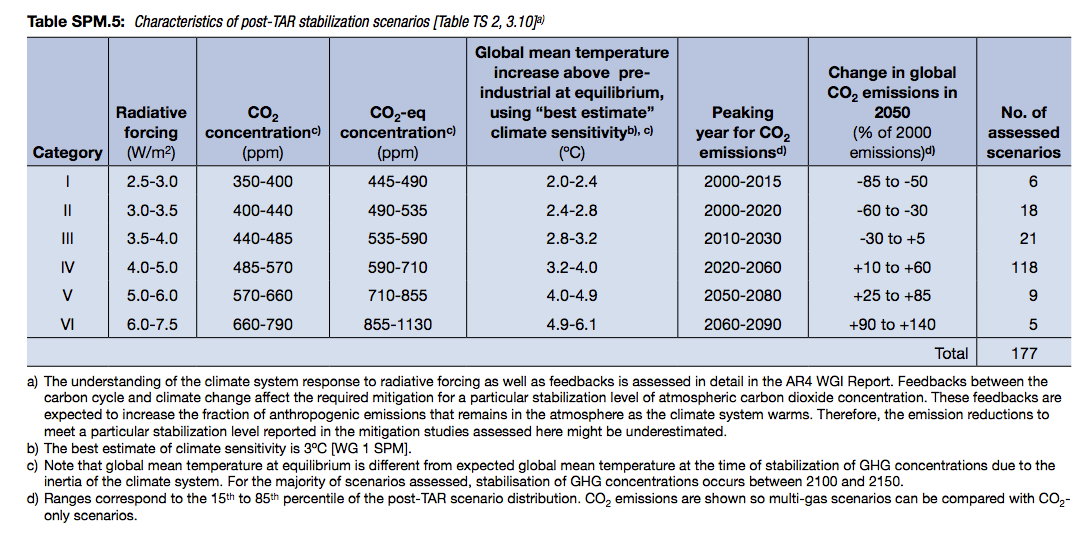

Thus problem #1 is that this article never should have been written, and doing so was a great example of irresponsible journalism, as climate scientist Kevin Trenberth told Climate Progress. Problem #2 is that The Economist’s interpretation of the information from the draft IPCC report is wrong. A similar table is shown in the 2007 IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) (Table SPM.5):

This is the table referenced in The Economist article showing a 2.0–2.4°C global mean surface temperature warming in response to a CO2-equivalent (the warming from all greenhouse gases, not just CO2) concentration of 445–490 parts per million (ppm). Note that this corresponds to a CO2 concentration of about 350–400 ppm – in other words, we’re already there. Right now cooling from human aerosol emissions is roughly offsetting the warming from non-CO2 greenhouse gases; the problem is that greenhouse gases have a long life in the atmosphere, and aerosols do not. As we transition away from coal energy and reduce pollutant emissions, their associated cooling effect will also decline, and will no longer mask the warming from non-CO2 greenhouse gases. Thus they must be accounted for in this CO2-equivalent calculation.

The Economist article makes some more mistakes when discussing this issue (emphasis added):

“[according to the draft AR5 table], at CO2 concentrations of between 425 parts per million and 485 ppm, temperatures in 2100 would be 1.3-1.7°C above their pre-industrial levels. That seems lower than the IPCC’s previous assessment, made in 2007. Then, it thought concentrations of 445-490 ppm were likely to result in a rise in temperature of 2.0-2.4°C.

The two findings are not strictly comparable. The 2007 report talks about equilibrium temperatures in the very long term (over centuries); the forthcoming one talks about them in 2100. But the practical distinction would not be great so long as concentrations of CO2 and other greenhouse-gas emissions were stable or falling by 2100.”

The bolded text decribes the difference between the AR4 and AR5 tables. One describes the warming as of 2100 (AR5), the other describes the eventual warming once the planet reaches a new equilibrium energy state (AR4). The Economist staff seem to think the difference is also in part due to a change in climate sensitivity values - that is not the case. According to an IPCC reviewer we talked to, both tables appear to be based on an equilibrium climate sensitivity of 3°C for doubled CO2. It's important to bear in mind that the world won't end in 2100 (we hope!) – there's nothing magical about that date, and the planet will continue warming until we get our greenhouse gas emissions down near zero.

The Economist is also wrong to say the practical difference between short-term transient warming and long-term equilibrium warming is ‘not great’ if greenhouse gas concentrations are stable or falling. In order to achieve no further warming, net greenhouse gas emissions must be zero or negative. Only in that scenario can atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations fall, offsetting the ‘warming in the pipeline’ to be achieved once the planet reaches a new equilibrium energy state.

The rest of the article is based on the fact that at the moment, the draft IPCC AR5 physical science report has reduced the lower end of the “likely” equilibrium sensitivity range from 2°C in AR4 to 1.5°C. Again, the report is still in draft form, and that is subject to change. Based on this, The Economist speculates,

“That seems to reflect a growing sense that climate sensitivity may have been overestimated in the past and that the science is too uncertain to justify a single estimate of future rises.

If this does turn out to be the case, it would have significant implications for policy. Many countries’ climate policies are guided by the IPCC’s findings. They are usually based on the idea (deriving in part from the IPCC) that global temperatures must not be allowed to increase by more than 2°C above pre-industrial levels, and that in order to ensure this CO2 concentrations should not rise above 450 ppm. The draft table casts doubt on how solid the link really is between 450 ppm and a 2°C rise.”

This builds on an earlier article by The Economist discussing a few recent studies that estimated climate sensitivity a bit lower than the IPCC AR4 best estimate. Michael Mann and I published an article in ABC explaining the problems with that piece. Long story short – the full body of evidence suggests that climate sensitivity is approximately in the range estimated in the IPCC AR4 report. Some recent studies have arrived at lower estimates, but may contain flaws, and other recent studies have arrived at higher estimates.

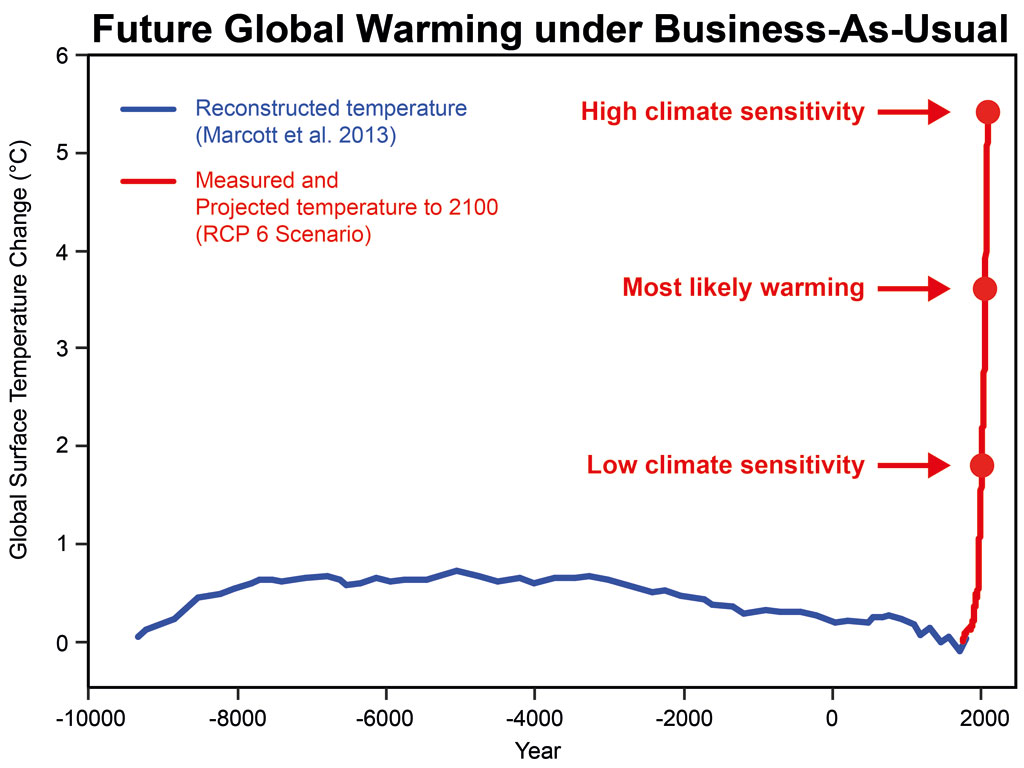

More importantly, even if equilibrium climate sensitivity were as low as this best case scenario of 1.5°C global surface warming in response to a doubling of atmospheric CO2, we’re still not doing enough to reduce emissions if we want to avoid dangerous climate change. The Economist misses the big picture. The figure below illustrates the amount of warming we can expect if we continue on a business-as-usual path with continued reliance on fossil fuels and a slow transition to low-carbon energy sources (IPCC scenario RCP 6) for equilibrium climate sensitivities of 1.5°C (best case), 3°C (most likely), and 4.5°C (worst case), compared to the climate experienced during the history of human civilization.

Image created by John Cook and Dana Nuccitelli, added to the SkS graphics page.

Even that “best case” is a dangerous level of climate change if we continue with business as usual rather than taking serious steps to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions. In any case, The Economist’s claim that “The draft table casts doubt on how solid the link really is between 450 ppm and a 2°C rise” is simply a misinterpretation of the draft IPCC report. The table simply indicates that 450 ppm CO2-equivalent (which we’ve already reached) would not lead to 2°C global surface warming until sometime after the year 2100. But since we’re already at that level and our greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise fast, that’s kind of a moot point anyway.

In fact, we’ve learned from reviewers of the draft IPCC AR5 report that the scenario in question (1.3–1.7°C global surface warming by 2100) applies to IPCC emissions scenario RCP 3-PD. In this scenario, after peaking in 2020, our annual CO2 emissions decline at a rate of around 3.5% per year. Human greenhouse gas emissions actually become negative after about 2070, meaning we remove more CO2 from the atmosphere than we add. The scenario they’re considering involves extremely aggressive greenhouse gas emissions reductions.

We recommend that everyone write this article off as a case of terrible judgment by The Economist that led to a factually wrong article. We hope their staff will learn from the many mistakes made in today’s piece and think twice before publishing articles based on draft reports next time.

Arguments

Arguments

The consistency of the comparisons is established quite easilly. The ratio between the transient climate response (reported in AR5 draft) and the equilibrium climate sensitivy (reported in AR4) is about two thirds. Thus the values reported in AR4 equate to transient responses of 1.3 to 1.6 C, compared to the 1.3 to 1.7 C reported in the AR5 draft. The slight difference is to small to matter.

Well-done, Dana: cue the denialati in 3.... 2... 1.....

I am sure that, as their fallacious assertions get more and more debunked, they are going to get more and more shrill, and more and more nasty. Hang onto your hats, kids.....

Tom@1,

Actually, on the Figure 5 in Dana's link to AR5 scenarios, in the RCP 3-PD scenario, the deltaT stays in at 1.7C and does not rise beyond 2100 suggesting it to be this scenario's equilibrium, rather than theoretical equilibrium of 1.7*1.5 = 2.55C.

I haven't read AR5 yet (no point doing it if I'm not a reviewer), but the key fallacy and misrepresentation by Economist here, appears to be that they tried to equate the RCP 3-PD scenario with Category 1 of TAR. Those are quire different scenarios. Category 1 TAR assumed emissions dropping after 2050 but staying positive throughout; while RCP 3-PD assumes emissions dropping below zero in 2070. Not realistic IMO, but the ingenuity of our children may do miracles. That would suposedly result in CO2 decline in second part of XXI and T not go to the 3Wm-2 equilibrium but stabilise around 2070 levels. The radiative forcings of AR5 scenarios are shown precisely here. BTW, anyone knows what "PD" stands for in RCP 3-PD acronym?

So, have the Economist reviewed carefuly the differences between TAR and AR5, they would not make such stupid comment. But from their narrative, it looks like they did not even bother distinguishing between equilibrium T and 2100y T, so it's hardly surprising they cannot understand the language of IPCC reports.

Chriskoz @3, having had a closer look, it appears that you are correct and I am wrong.

Having said that, the radiative forcing of RCP 3-PD peaks at just over 3 W/m^2 in 2045, and drops to 2.6 W/m^2 by 2100. Were the radiative forcing held constant at 3 W/m^2, it would take approximately 200 years to reach the equilibrium climate sensitivity. Alternatively, had the radiative forcing been held constant from the time it reached 2.6 W/m^2 (2021), it would likewise take two hundred years to reach equilibrium climate sensitivity. It is unlikely, therefore, that in the RCP 3-PD scenario that equilibrium climate sensitivity will be reached in 2100.

So, not only does the Economist compare different scenarios, but they do not compare strictly equivalent values. Their fudge that "...the practical distinction would not be great so long as concentrations of CO2 and other greenhouse-gas emissions were stable or falling by 2100" is unsound.

chriskoz: the 'PD' stands for 'peak and decline'.

The other scenarios are named after the w/m2 forcings - whereas RPC 3-PD posits a maximum of 3 w/m2, dropping to 2.6 w/m2 by 2100. I think it's confusing however, and elsewhere I've seen rather critical reactions to it as a pathway due to the rather unlikely nature of the scenario.

IPCC Statement:

www.ipcc.ch/pdf/ar5/statement/statement_wg3_table.pdf

GENEVA, 19 July -

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) notes that an article has been published in The Economist citing a table that appears in the second order draft of the IPCC Working Group III contribution to the IPCC's Fifth Assessment Report.

This draft, like any IPCC draft, is the result of the IPCC's iterative process of writing and review process and thus a work in progress. The text is likely to change in response to comments from government and expert reviewers. It is therefore premature and can be misleading to attempt to draw conclusions.

I find the plot quite puzzling. Do the 3 labeled points have different x values? Presumably not; I assume there are 3 overlapping lines that look like one line. For clarity I suggest that thinner lines of different colors be used, or perhaps an inset that shows what is happening in that thin slice of time.

ianw01@7, you said:

You're incorrect. Look at the timescale, draw the other X values of your interest and you'll see that, although 2000 and 2100 are different, their diffference on that plot is ~ one pixel.

I diagree with you that the inset is required to show what's happening between 2000-2100 because I see that graph as the summary of what was happening in the Holocene (human civilisation time), and the red line indicates the end of Holocene as we know it (some call this new period Anthropocene), there is no need to obstruct this simple picture with the "squeezed to timescale" AR5 scenarios picture refered to earlier, that lead to the red line.

chriskoz@8: I'm not quite following you, but let me try:

The article says the figure shows "the amount of warming we can expect .... for equilibrium climate sensitivities of 1.5°C (best case), 3°C (most likely), and 4.5°C (worst case)"

If I take your response, that the dots do have different x-values, then the clear (but steep) slope between the points indicates that in addition to the different amounts of warming, it will take longer to reach the peak for each climate sensitivity?

If I have it right now, I'd argue for a short dotted tail branching out to the right of each dot indicating that there are alternate trajectories for each sensitivity.

The unsettling aspect is that it seems to portray in inevitable climb past the "low sensitivity" red dot, no matter what. I don't want to beat this issue to death, but this logical inconsistency undermines the credibility of the graphic.

ianw01 is right - the graph is wrong

and it's closer to 10px/100 yrs

and why does the graph combine measured and projected into one color?

ianw01, chriskoz, bvee:

1) The graph displays 7.4 pixels per century as measured on Paint.

2) The low climate sensitivity mark is displaced by four pixels relative to the high climate sensitivity mark, whereas logically they should by on the same point on the x-axis.

3) Displaying the three possible outcomes shown seperately would merely cause an indistinguishable wedge, removing clarity. I do not see how the loss of clarity and visual simplicity would be compensated by so small a gain in logical coherence.

4) We can take the red line to be the modelled result for historical and projected forcings with a high climate sensitivity with RCP 6.0 The modelled temperatures in such a case would not differ from oberved temperatures by more than the value of half a pixel, and so would be indistinguishable. The low and modal values would properly be indicated by a line across from the right y-axis in that case. So considered, the criticisms of the graph come down to one of style. This shows them to be entirely trivial.

i'm not criticising the style - ie line weight and title. although i do like the hue of blue used.

i am saying the graph indicates that models are insensitive to climate sensitivity.

Apologies if this is a naive question, but could it not be that CS has a different value depending on the prevailing conditions?

Global temperatures seem to have been pretty unstable during the ice ages, and rather more stable in the interglacials. CS figures derived from paleolithic cold conditions may be accurate in regard to those states of the planet, but not relevant to modern conditions. The previous three interglacials maxed out consistently at a couple of degrees Celsius warmer than present times, so there does seem to be a natural upper limit of planetary temperature, in the absence of the kind of GHG changes that we have unfortunately brought about.

So my question is - could it be that the high "tail" of GHG values (that is, higher than 4.5C) is not due to any errors of climate science, but simply represent values that are not relevant to our stage in the cycle?

Richard Lawson @14, climate sensitivity does vary based on temperature and arrangement of continents (and probably other factors as well). However, across the very broad range of conditions that have existed for the last 500 million years, climate sensitivities of 3-4 C have been a consistent feature. Further, high end climate sensitivities have been associated with both very warm and very cold conditions in the past.

So, we may have lucked out into an era of unusually low climate sensitivity (although the continental arrangement suggests otherwise), but the odds are against it. Further, even if we have, there will be a temperature threshold which, if we pass, will result in a greater climate sensitivity. If that threshold is within the range of temperatures we will reach with global warming and a low climate sensitivity, the result will be warming consistent with a high climate sensitivity, but with a slow initial warming lulling us into a false sense of security.

Tom Curtis @12: I respectfully disagree with your assertion that the differences are purely of style and therefore trivial. They are neither. Note that chriskoz@8 tells me that I'm wrong - that the red dots do not have the same x-value. You tell me they they "logically" should have the same x-value. It now seems you both support the graph, yet you interpret it differently.

I'm not so concerned with who is right or wrong. I just would like to be able to look at the graph and know what it is supposed to convey.

Here is its fundamental fault: any reader who first sees this plot needs to do some re-reading and deduction to realize that it represents 3 different scenarios. All they will see intially is a single path with 3 points along the way.

At a more detailed level, what a viewer of the plot (or I still) can't tell is whether, for each scenario, the climate models predict a different time to equilibrium that should be distinguishable on this plot. The plot makes me wonder whether the red dots were all put on one line for the sake of expediency (No offense, John & Dana!)

Given that the plot is intended to show time to equilibrium, then very short horizontal tails to the right would clarify the plot tremendously. They would immediately and graphically make clear that

I'm grateful for the work that went into the artilcle and graphic, but I'm being picky because I believe a graphic like this (in the library) needs to be clear and not open to mis-interpretation or easy criticism. Confusion is the lifeblood of climate science deniers.

bvee @10: Thanks.

Tom Curtis @12:

I second ianw01@16 - I think that aligning the three data points vertically would add clarity rather than remove it. Looking at the graph, I found myself second-guessing my understanding that the three data points were supposed to be all at the year 2100, because I could visually detect that they are not vertically aligned by noting the shrinking gap between the points and the right side of the graphic.

From the original article: "The figure below illustrates the amount of warming we can expect [my and ianw01's question is, by when? 2100?] if we continue on a business-as-usual path with continued reliance on fossil fuels and a slow transition to low-carbon energy sources (IPCC scenario RCP 6) for equilibrium climate sensitivities of 1.5°C (best case), 3°C (most likely), and 4.5°C (worst case), compared to the climate experienced during the history of human civilization."

If the RCP 6 scenario is supposed to be projected out to 2100 for each of the three climate sensitivities, how about showing three different curves, perhaps all red, but with a slightly lighter lineweight to avoid the "indistinguishable wedge" problem that Tom mentions? Or even with the heavy lineweight, I think the overlap between the lines would be less confusing than the three points not being vertically aligned.

As still a third option, which would avoid the line-overlap/"indistinguishable wedge" problem, you could animate the graphic, cycling through the projections for the respective climate sensitivities, only displaying one at a time. The legend itself could also cycle between "(RCP 6 scenario with 1.5 C sensitivity)," "(~ 3 C sensitivity)" and "(~ 4.5 C sensitivity)."

ianw01,

On rereading the posts and on closer look, it turns out I was wrong @8 (sorry) and you are right that the last plot is somewhat ambigous as to what those red points actually mean.

I very much like jdixon1980@7 suggestion in the last paragraph to animate the graph over three sensitivities. That would remove the issue and enhance & clarify the graph at the same time.

Many thanks Tom Curtis @15. OK I have another question. I have been puzzled about the recent slew of papers giving low climate sensitivity. Then I read that the low CS papers are based on simple Energy Budget models, and that the more complex general circulation models which deal with more factors will deliver higher CS values.

Is that correct?

Richard@19,

You're correct.

For example, simple Energy Budget models ignore the albedo change from sea ice/ice sheet melt, also the permafrost melt and methane clathrate release is ignored. That's because the machanics or the extents of those feedbacks are unknown. However, with more data about recent sea ice melt, I expect the sensitivity figures will be updated upwards in the near future.

Richard Lawson @19, I would be interested in how you found that "slew" of papers. A search of google scholar for "climate", "sensitivity" post 2008 returned 282,000 hits. I doubt you have read even 10% of them so as to be able to determine that they are dominated by low sensitivity results. I suspect that you may have read about the "slew" of papers on some denier site where (if they are like Patrick Michaels or WUWT), they only report the few papers returning a low climate sensitivity and not those many others reporting a high climate sensitivity. Thus they will not have reported on Haywood et al, (2013) which reports climate sensitivities from 2.7 to 4.1 C per doubling of CO2 from a comparison of the output of eight models with pliocene conditions (table 2). Nor on Eagle et al (2013), which report a high regional climate sensitivity in central China. Nor on Li et al (2013), which report a climate sensitivity of 5.4 C per doubling of CO2. Nor (finally) on Previdi et al (2011), who report that the Earth System Sensitivity, ie, the climate response allowing for slow feedback such a the retreat of ice sheets etc, may well have an impact in periods short enough to be relevant to policy.

However, it is not true that all recent low climate sensitivity estimates have been based on simple energy budget models, nor that their use are the cause of the low estimate. Schmittner et al, for example, use the Uvic earth system model, but reach their low sensitivity estimate because of the (probably unrealisticly) low estimate of the difference in temperature between the LGM and the present. Nic Lewis's recent two recent efforts (only one of which was peer reviewed) have low sensitivities at least in part because they do not allow for the effects of recent La Nina's (which will cause the estimated climate sensitivity to be low).

ianW01 & jdixon1980,

1) I modified the graph in question so that all three red circles align with 2100, and added a trend line from the end of the observational data to 2100 for each. Here is the result:

You may think there is a gain in visual clarity, but I do not.

2) The original graph does not cause any confusion if you do not assume graphs can be interpreted independently of their accompanying text. In the case, the accompanying text, ie, the legend, clearly states:

That legend precludes interpretations in which the red dots are considered to indicate temperatures other than at 2100.

3) In that regard, ianWO1's interpretation of the graph (@16) as showing the time to equilibrium temperature is entirely unwarranted. In fact, in scenario RCP 6.0, forcings do not peak until about 2150 and temperatures are still rising at 2300. Beyond 2300, whether or not temperatures will reach, exceed or fall short of the equilibrium for the Charney Climate Sensitivity depends on a number of factors outside the scope of the scenario. Further, depending on those factors temperatures may be unstable for millenia, although rates of change are unlikely to match those in the twentieth century, much less the twenty-first.

4) I also like jdixon1980's suggestion for an animated gif and think it would be a superior presentation. On the other hand, I am not prepared to prepare it myself, and therefore am disqualified from criticizing other people who have voluntarilly surrendered their own time to prepare the original graph for not spending more of their own time to make the superior product. Perhaps jdixon would volunteer?

don't spend anymore time on graph, it's over-reaching.

Tom Curtis @21. Many thanks again for your response. Yes, the impression I had was from the discussion on CS that is penetrating through to the general news, where the picture is that CS values are being revised downwards by recent work. It was an Economist article that stated that EB models gave lower values than GCM models.

There are a few of us out here, non climatologists who are engaging in the thankless and often depressing task of debating with delayers on blogs and Twitter. We do search sks &c for answers, but there is often no answer to a specific question, which is why it is so useful to be able to put questions here.

It might be useful if sks had a dedicated standing page for us to put questions which arise from the debate.

Richard Lawson @24, a dedicated question page would be a nice addition to SkS, and has been suggested before. It, like a number of other good suggestions has been side lined because the time available from volunteers is limited, and a number of other very worthwhile projects have been pursued instead. (The Consensus Project comes to mind.) However, we live in hope, and as I am not in on current planning, one may be coming soon (or not).

From "Commie" Hedegaard, Europe's climate action commissioner, said:

"Let's say that science, some decades from now, said 'we were wrong, it was not about climate', would it not in any case have been good to do many of things you have to do in order to combat climate change?."

EU policy on climate change is right even if science was wrong, says commissioner