New research: climate may be more sensitive and situation more dire

Posted on 5 July 2016 by dana1981

Scientists use a variety of approaches to estimate the Earth’s climate sensitivity – how much the planet will warm as a result of humans increasing greenhouse effect. For decades, the different methods were all in good general agreement that if we double the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, Earth’s surface temperatures will immediately warm by about 1–3°C (this is known as the ‘transient climate response’). Because it would take decades to centuries for the Earth to reach a new energy balance, climate scientists have estimated an eventual 2–4.5°C warming from doubled atmospheric carbon (this is ‘equilibrium climate sensitivity’).

However, a 2013 paper led by Alexander Otto disrupted the agreement between the various different approaches. Using a combination of recent climate measurements and a relatively simple climate model, the ‘energy budget’ approach used in Otto’s study yielded a best estimate for the immediate (transient) warming of 1.3°C and equilibrium warming of 2.0°C; within the agreed range, but less than climate model best estimates of 1.8°C and 3.2°C, respectively.

This new energy budget approach, which was replicated by several subsequent studies, seemed to indicate the Earth’s climate is a bit less sensitive to carbon pollution than previously thought. As a result, the IPCC adjusted its estimated range for equilibrium climate sensitivity from 2–4.5°C in its 2007 report to 1.5–4.5°C in its 2014 report. This suggested perhaps a slightly less dire climate situation.

New finding: disagreement due to apples-to-oranges comparison

Later in 2013, Kevin Cowtan and Robert Way published a paper finding that climate scientists had been underestimating global surface warming, largely because of a lack of measurements in the rapidly-warming Arctic. Additionally, while climate models simulate surface air temperatures (the temperature of the air a few meters above the Earth’s surface), over the oceans, climate scientists measure sea surface temperatures. It turns out that the water surface isn’t warming quite as fast as the air above it. Thus looking at modeled surface air temperatures versus measured global land-ocean surface temperatures is an apples-to-oranges comparison.

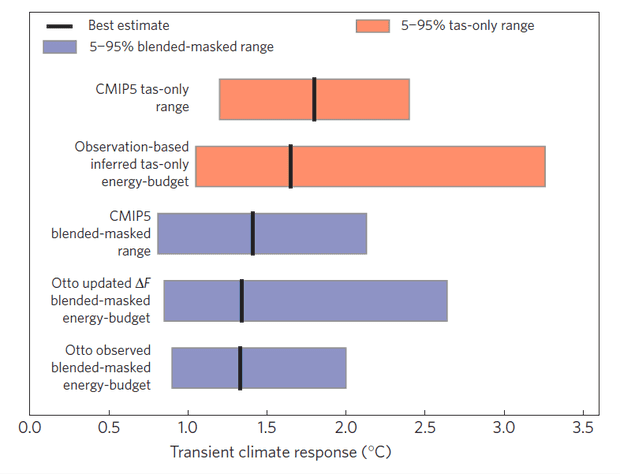

A new study in Nature Climate Change led by Mark Richardson in collaboration with Kevin Cowtan, Ed Hawkins, and Martin Stolpe accounts for these differences to make an apples-to-apples comparison. They find that the use of sea surface temperatures biases the Otto result low by about 9%, and the lack of Arctic observations by another 15%. When observations are adjusted to estimate surface air temperatures (red bars in the figure below), or when models are adjusted to estimate land-ocean surface temperatures (blue bars), the estimated transient climate response from climate models and the Otto approach are in close agreement.

Like-with-like comparisons of transient climate response estimates between models and observations. In the upper two bars, the observed estimates are adjusted to match the method used for the models. In the lower three bars the model outputs are treated in the same way as the observations. Illustration: Richardson et al. (2016); Nature Climate Change.

Climate sensitivity may be higher yet

Previous studies have identified other flaws in the energy budget model approach. Several papers, most recently led by Kate Marvel at NASA, found that Otto’s and similar studies have not accounted for the different efficiencies of various factors that cause global energy imbalances. Other papers have noted that the energy balance model approach assumes that feedbacks amplifying or dampening global warming will stay constant over time, while in reality, some feedbacks kick in later than others. This suggests that energy budget climate sensitivity estimates, based only on today’s feedbacks, will be biased low.

The new Nature Climate Change paper didn’t address how much combining these various corrections would change our estimates of the Earth’s climate sensitivity.As the authors noted:

A recent study, Marvel et al 2015 and prior works suggest that cooling effect of non-CO2 pollution may have been underestimated. This also suggests that climate sensitivity is underestimated (since the net direct impact of human activity would be reduced, requiring a greater sensitivity to achieve the observed temperature change).

The results of Marvel et al are independent of [our] work. If both studies are correct, climate sensitivity from the historical record could be higher than climate sensitivity from the models. However we are not in a position to comment on that paper, and so draw the weaker conclusion that the historical record offers no reason to doubt the estimates of climate sensitivity from climate models.

According to lead author Mark Richardson:

The work that’s out there now, if anything, favours hotter models in general. Now it’s clear there’s no evidence from this energy-budget approach for a cooler-than-models future. But there are lots of things where the numbers haven’t been fully calculated yet. We don’t know precisely how Marvel’s results apply to the real world yet and other factors could matter, such as recent hints from CERN laboratory results on how clouds form. This helps explain why we have such a large range of possible transient climate response values (1.0–3.3°C is a pretty big range!), but even so, our results say that we’re more than 99.9% confident that most recent global warming is human-caused.

Bad news for the “skeptic” case

This new research shows that their arguments are on even weaker footing than previously thought.

Arguments

Arguments

The issues in this article, along with equilibrium observed over a compressed time cycle may be responsible for much of the difference between paleoclimate approximations of sensitivity and modern estimations. I've always tended toward the post-diction estimates of paleoclimate research for this issue and assumed that the differences between the values they indicate and modern assessments to be primarily the result of things we either haven't yet understood (properly or entirely - to include aerosols/clouds and various other known and unknown feedback systems).