A new two-part study published in Climatic Change by a team of scientists led by Stephan Lewandowsky examines mathematically what happens to the risks posed by climate change when the scientific uncertainty increases. Part 1 of the study explores two important points.

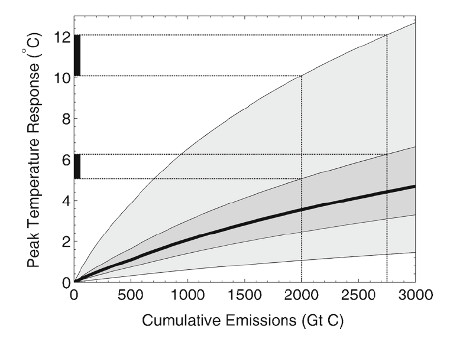

First, the probable range of climate sensitivity to the increased greenhouse effect isn't symmetrical. Instead, based on the available evidence and research, it's more likely that we'll see a large amount of global warming than a small amount in response to rising carbon emissions. By itself, this means that more climate uncertainty translates into an even bigger risk of painful consequences than relatively benign consequences. More uncertainty means a slightly better chance of the low warming outcomes, but it also means an even bigger chance of the high warming outcomes, because the scientific data have a harder time ruling those out.

The second critical point is that economic models agree that once we reach a certain tipping point, the costs of climate damage increase at an accelerating rate. The models don't agree on exactly where that tipping point lies, but they do agree on the shape of the curve and the acceleration of the climate damage costs once we pass that tipping point (even the 'skeptics' agree on this).

Lewandowsky's team combined the shape of the curve showing the probable values of the Earth's climate sensitivity with the shape of climate economic costs curve, and came to an inescapable conclusion: more climate uncertainty means the expected damages from climate change are higher.

In fact, because both curves are more heavily weighted on their high sides (greater probability of high climate sensitivity than low, and climate damage costs accelerating with more warming), this conclusion holds true even if the shape of one of the curves changes. For example, even if climate sensitivity is equally likely to be low as high, the accelerating nature of climate damage costs with more warming would still mean that greater climate uncertainty translates into more climate damages.

Part 2 of the study also shows that greater climate science uncertainty means we're more likely to blow past the internationally accepted 'danger limit' of 2°C global surface warming. To meet that target we have a certain carbon emissions 'budget,' but there's also uncertainty associated with the exact size of that budget. If the total budget turns out to be less than the emissions we have already pumped into the atmosphere, then mitigation has already failed to keep temperatures below the 'danger limit.'

With more climate uncertainty, the range of possible carbon budget sizes becomes wider. The shape of this curve also means that the average estimated carbon budget value increases. This means that with more uncertainty we're more likely to think the budget is larger than it actually is, and hence we're more likely to miss our target and cause dangerous global warming.

Arguments

Arguments

Gravity rules.

The airplane has run out of fuel and is going down. The crew is looking for the best place to land, we may find a soft field or we may crash hard. We are uncertain of the exact location.

Uncertainty does not mean that it won't happen.

Poster::Your comment is off-topic and therefore was deleted.

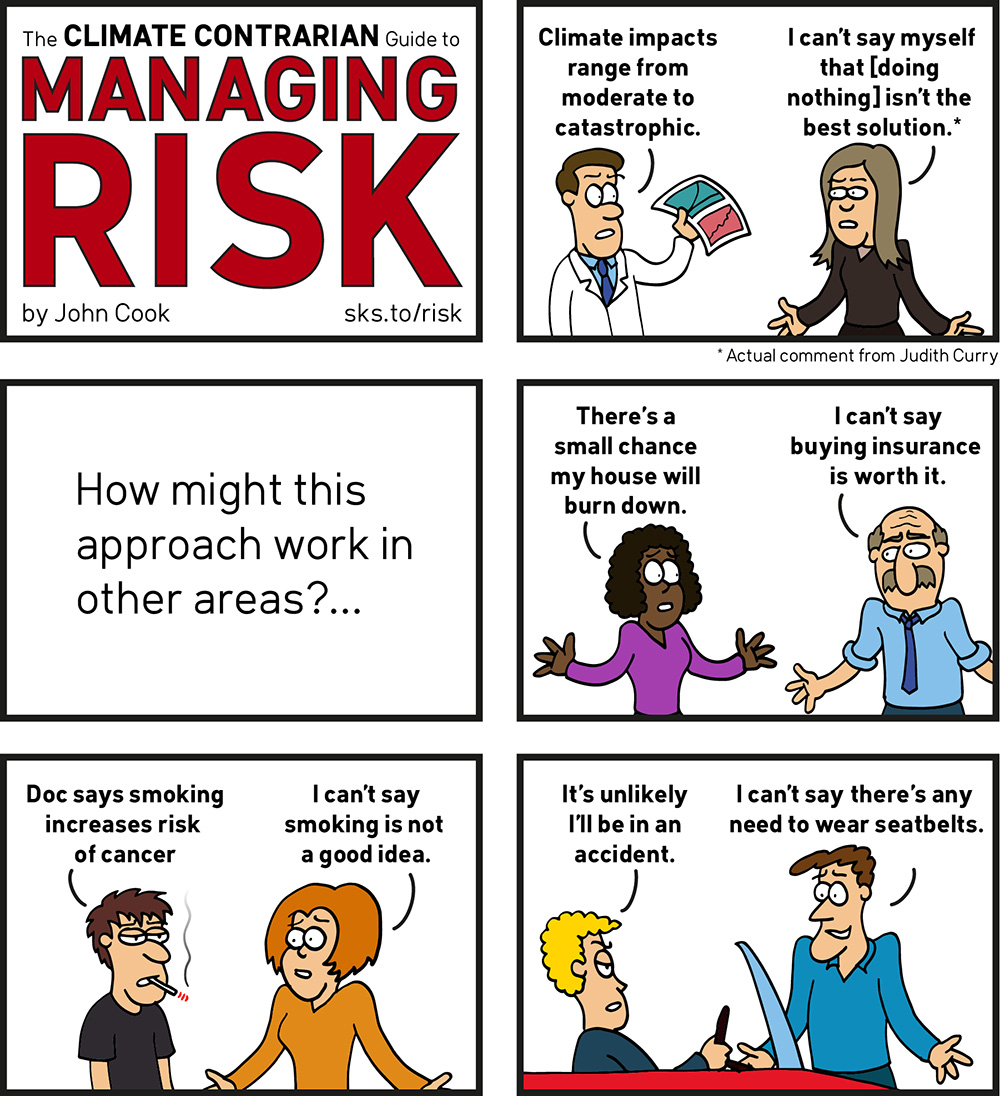

The idea is familiar. In fact, I just sent a letter to my congressman in response to his response to an earlier one I sent him. He indicated that the cause of global warming was still in doubt and called (twice) for more study. I argued that we know enough to be aware that the risk is high, and the need to act is urgent. I quoted this excerpt from William Nordhaus's devastating analysis of the letter that sixteen scientists (if you include some engineers and an astronaut/senator in the count) published in the Wall Street Journal in 2012, in which they cited Nordhaus to buttress their position that it was best to do nothing about global warming. He rejected the position they attributed to him and, on the idea of uncertainty as a basis for doing nothing, he wrote,

"One might argue that there are many uncertainties here, and we should wait until the uncertainties are resolved. Yes, there are many uncertainties. That does not imply that action should be delayed. Indeed, my experience in studying this subject for many years is that we have discovered more puzzles and greater uncertainties as researchers dig deeper into the field. . . . Policies implemented today serve as a hedge against unsuspected future dangers that suddenly emerge to threaten our economies or environment. So, if anything, the uncertainties would point to a more rather than less forceful policy—and one starting sooner rather than later—to slow climate change."

Richard Alley made the same point in a lecture, saying, "The less you trust me, the more worried you should be."

The new research is a welcome addition to buttress this argument.

Reading the summary from the University of Bristol I am puzzled by this comment " Scientists have shown that as uncertainty in the temperature increase expected with a doubling of carbon dioxide from pre-industrial levels rises, so do the economic damages of increased climate change. Greater uncertainty also increases the likelihood of exceeding ‘safe’ temperature limits and the probability of failing to reach mitigation targets" Why is the uncertainty focussed only on increases in temperature (and on sea level rises)? Surely if the uncertainty in rises is increasing, isn't the uncertainty of stabiity or even falls in temperatures (and falls in sea levels) also increasing. Why does greater uncertainty also not increase the likelihood of not exceeding "safe trmperatures'? Why is ths aspect not considered worth a mention?

Poster:

The conclusion is based on how financial risk is calculated. If there are multiple possible outcoomes, you have to take into account the cost of all possible outcomes, weighted by the probability of each of those outcomes.

Increasing uncertainty increases the probability of both high and low cost outcomes. However the shape of the cost curve is such that the finacial risk, calculated using the above method, increases.

This is the standard approach used by insurers, investors and gamblers for decades or centuries, however the issue is clearly confusing to a lot of people.

Poster - This is tendency, for uncertainties to increase the cost risks, is exacerbated by the near lognormal distribution of sensitivity estimates. The high tail of sensitivity estimates is much longer than the low tail, meaning that for equal probability estimates the weighted high end will increase the total risk cost far more than the equal probability weighted low end will decrease total risk cost.

Add the asymmetric sensitivity estimate to the rise in risk cost due to larger uncertainty spreads, and the financial risk is considerably higher than if we had a highly constrained estimate of climate sensitivity. Uncertainty is not our friend.

Re: KR's mention of the 'long tail:' here's but one good explication of why this is a critical, but oft-overlooked aspect of what turns out to be a widespread and poor understanding of risk analysis.

http://earlywarn.blogspot.com/2010/05/explaining-long-tail-climate-risk.html

Poster... Just to add a good visual for what KR is saying about asymmetry:

good post, giving context to the risk management nature of climate change

minor detail: IMHO, the text stating

"... the accelerating nature of climate damage costs with more warming would still mean that greater climate uncertainty translates into more climate damages."

should better be

"... the accelerating nature of expected climate damage costs with more warming would still mean that greater climate uncertainty translates into higher risks of climate damages."

since uncertainty does not directly translate to higher costs, by higher risks. The change keeps it more consistent with the remaining text, I think.

A few points:

1. I am pretty sure that the scientific global average surface temperature increase of concern has been, and continues to be, 1.5 decgrees C. That is the temperature beyond which climate changes are likely to become less predictable combined with being more signficant. The 2 degree C limit is the result of global leaders in Copenhagen acknowledging that the failure of the most fortunate to significantly reduce the impacts of their lifestyles, including exporting larger amounts of their impacts to nations like China and India, has made it very unlikely that impacts can be limited to a 1.5 degree C increase.

2. The economic evaluations ignore one critical aspect. The people expecting to benefit most from failing to reduce the burning of fossil fuels is not the group that is expected to suffer the consequences of their irresponsible unsustainable and damaging activities.

3. The economic evaluations also typically ignore the fundamental unsustainability of burning fossil fuels. And they ignore far more unsustainable and damaging consequences than the results fo the excess CO2 that is produced.

4. Many economic evaluations actually discount the future costs, claiming a future cost is not as important as a current benefit. Though this is a valid way of evaluating alternative investment opportunities, it is a totally inappropriate way of evaluting the merits of current day activities. The only legitimate value of a current day activity is the benefit obtained into the future. By that measure it is clear that the current burning of fossil fuels is essentially a worthless activity.

Comment@10. You,apparently, blithely ignore the burnign of fossil fules by the internal combustion engine. This aspect of the "West's" profligacy is rarely mentioned as too many in the "profligate West" rely on this to maintain their lifestyle, Rather than focus on "solar and wind" more Draconian actions on use of the ICE would be appropriate

Poster @ 11:

I'm not sure I follow the basis for your comment that I ignore the burning of fossil fuels in the internal combustion engine. My third point is the catchall of the unacceptability of any burning of fossil fuels. That activity is not just fundamentally unsustainable, putting at risk the future of any economy or society that relies on it, but it creates many harmful unsustainable results in addition to the excess CO2.

My fundamental position is that the only future for humanity is for all human activity to be 'restricted' to truly sustainable activity as part of a robust diverse web of life on this amazing planet.

So my view not only includes the need to curtail any burning of fossil fuels, it includes the need to ciurtail any consumption of non-renewable resources. The only acceptable use of a non-renewable resource should be no accumulating damage done getting the resource and converting it into a useful product and absolutely full recycling of the material...forever...

Humanity has several hundred million years to enjoy on this planet. They can't consume it along the way. The same applies to any thoughts of spreading life beyond this planet. If what we spread is the current attitude we spread a damaging disease, not sustainable life.